Conodont

It has been suggested that Conodont feeding apparatus be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2024. |

| Conodonts Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Conodont elements | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | †Conodonta Pander, 1856 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Conodonts (Greek kōnos, "cone", + odont, "tooth") are an extinct group of jawless vertebrates, classified in the class Conodonta. They are primarily known from their hard, mineralised tooth-like structures called "conodont elements" that in life were present in the oral cavity and used to process food. Rare soft tissue remains suggest that they had elongate eel-like bodies with large eyes. Conodonts were a long-lasting group with over 300 million years of existence from the Cambrian (over 500 million years ago) to the beginning of the Jurassic (around 200 million years ago). Conodont elements are highly distinctive to particular species and are widely used in biostratigraphy as indicative of particular periods of geological time.

Discovery and understanding of conodonts

[edit]The teeth-like fossils of the conodont were first discovered by Heinz Christian Pander and the results published in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1856.[2]

It was only in the early 1980s that the first fossil evidence of the rest of the animal was found (see below). In the 1990s exquisite fossils were found in South Africa in which the soft tissue had been converted to clay, preserving even muscle fibres. The presence of muscles for rotating the eyes showed definitively that the animals were primitive vertebrates.[3]

Nomenclature and taxonomic rank

[edit]Through their history of study, "conodont" is a term which has been applied to both the individual fossils and to the animals to which they belonged. The original German term used by Pander was "conodonten", which was subsequently anglicized as "conodonts", though no formal latinized name was provided for several decades. MacFarlane (1923) described them as an order, Conodontes (a Greek translation), which Huddle (1934) altered to the Latin spelling Conodonta.[4] A few years earlier, Eichenberg (1930) established another name for the animals responsible for conodont fossils: Conodontophorida ("conodont bearers").[1] A few other scientific names were rarely and inconsistently applied to conodonts and their proposed close relatives during 20th century, such as Conodontophoridia, Conodontophora, Conodontochordata, Conodontiformes,[5] and Conodontomorpha.

Conodonta and Conodontophorida are by far the most common scientific names used to refer to conodonts, though inconsistencies regarding their taxonomic rank still persist. Bengtson (1976)'s research on conodont evolution identified three morphological tiers of early conodont-like fossils: protoconodonts, paraconodonts, and "true conodonts" (euconodonts).[5] Further investigations revealed that protoconodonts were probably more closely related to chaetognaths (arrow worms) rather than true conodonts. On the other hand, paraconodonts are still considered a likely ancestral stock or sister group to euconodonts.

The 1981 Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology volume on the conodonts (Part W revised, supplement 2) lists Conodonta as the name of both a phylum and a class, with Conodontophorida as a subordinate order for "true conodonts". All three ranks were attributed to Eichenberg, and Paraconodontida was also included as an order under Conodonta.[6] This approach was criticized by Fåhraeus (1983), who argued that it overlooked Pander's historical relevance as a founder and primary figure in conodontology. Fåhraeus proposed to retain Conodonta as a phylum (attributed to Pander), with the single class Conodontata (Pander) and the single order Conodontophorida (Eichenberg).[4][7] Subsequent authors continued to regard Conodonta as a phylum with an ever-increasing number of subgroups.[8]

With increasingly strong evidence that conodonts lie within the phylum Chordata, more recent studies generally refer to "true conodonts" as the class Conodonta, containing multiple smaller orders.[9][10][11] Paraconodonts are typically excluded from the group, though still regarded as close relatives.[9][10][11] In practice, Conodonta, Conodontophorida, and Euconodonta are equivalent terms and are used interchangeably.

Conodont elements

[edit]Lone elements

[edit]Conodont elements consist of mineralised teeth-like structures of varying morphology and complexity. The evolution of mineralized tissues has been puzzling for more than a century. It has been hypothesized that the first mechanism of chordate tissue mineralization began either in the oral skeleton of conodonts or the dermal skeleton of early agnathans.

The element array constituted a feeding apparatus that is radically different from the jaws of modern animals. They are now termed "conodont elements" to avoid confusion. The three forms of teeth, i.e., coniform cones, ramiform bars, and pectiniform platforms, probably performed different functions.

For many years, conodonts were known only from enigmatic tooth-like microfossils (200 micrometers to 5 millimeters in length[12]), which occur commonly, but not always, in isolation and were not associated with any other fossil. Until the early 1980s, conodont teeth had not been found in association with fossils of the host organism, in a konservat lagerstätte.[13] This is because the conodont animal was soft-bodied, thus everything but the teeth was unsuited for preservation under normal circumstances.

These microfossils are made of hydroxylapatite (a phosphatic mineral).[14] The conodont elements can be extracted from rock using adequate solvents.[15][16][17]

They are widely used in biostratigraphy. Conodont elements are also used as paleothermometers, a proxy for thermal alteration in the host rock, because under higher temperatures, the phosphate undergoes predictable and permanent color changes, measured with the conodont alteration index. This has made them useful for petroleum exploration where they are known, in rocks dating from the Cambrian to the Late Triassic.

Full apparatus

[edit]-

Complete element set of the conodont Hindeodus parvus

-

Preserved articulated association of conodont elements belonging to the species Archeognathus primus (Ordovician, North America)

The conodont apparatus may comprise a number of discrete elements, including the spathognathiform, ozarkodiniform, trichonodelliform, neoprioniodiform, and other forms.[18]

In the 1930s, the concept of conodont assemblages was described by Hermann Schmidt[19] and by Harold W. Scott in 1934.[20][21][22][23]

Elements of ozarkodinids

[edit]The feeding apparatus of ozarkodinids is composed of an axial Sa element at the front, flanked by two groups of four close-set elongate Sb and Sc elements which were inclined obliquely inwards and forwards. Above these elements lay a pair of arched and inward pointing (makellate) M elements. Behind the S-M array lay transversely oriented and bilaterally opposed (pectiniform, i.e. comb-shaped) Pb and Pa elements.[24]

The conodont animal

[edit]-

Life restoration of Promissum pulchrum

-

Restoration of Panderodus unicostatus

-

A body fossil of Panderodus unicostatus

-

A size comparison of the three conodont species with preserved body fossils.

-

Fossils of Typhloesus, at one time considered the first conodont body fossil.

Although conodont elements are abundant in the fossil record, fossils preserving soft tissues of conodont animals are known from only a few deposits in the world. One of the first possible body fossils of a conodont were those of Typhloesus, an enigmatic animal known from the Bear Gulch limestone in Montana.[25] This possible identification was based on the presence of conodont elements with the fossils of Typhloesus. This claim was disproved, however, as the conodont elements were actually in the creature's digestive area.[26] That animal is now regarded as a possible mollusk related to gastropods.[26] As of 2023, there are only three described species of conodonts that have preserved trunk fossils: Clydagnathus windsorensis from the Carboniferous aged Granton Shrimp Bed in Scotland, Promissum pulchrum from the Ordovician aged Soom Shale in South Africa, and Panderodus unicostatus from the Silurian aged Waukesha Biota in Wisconsin.[9][27][28] There are other examples of conodont animals that only preserve the head region, including eyes, of the animals known from the Silurian aged Eramosa site in Ontario and Triassic aged Akkamori section in Japan.[29][30]

According to these fossils, conodonts had large eyes, fins with fin rays, chevron-shaped muscles and axial line, which were interpreted as notochord or the dorsal nerve cord.[27][31] While Clydagnathus and Panderodus had lengths only reaching 4–5 cm (1.6–2.0 in), Promissum is estimated to reach 40 cm (16 in) in length, if it had the same proportions as Clydagnathus.[27][28]

Ecology

[edit]

The "teeth" of some conodonts have been interpreted as filter-feeding apparatuses, filtering plankton from the water and passing it down the throat.[32] Others have been interpreted as a "grasping and crushing array".[28] Wear on some conodont elements suggests that they functioned like teeth, with both wear marks likely created by food as well as by occlusion with other elements.[33] Studies have concluded that conodonts taxa occupied both pelagic (open ocean) and nektobenthic (swimming above the sediment surface) niches.[33] The preserved musculature suggests that some conodonts (Promissum at least) were efficient cruisers, but incapable of bursts of speed.[28] Based on isotopic evidence, some Devonian conodonts have been proposed to have been low-level consumers that fed on zooplankton.[33]

A study on the population dynamics of Alternognathus has been published. Among other things, it demonstrates that at least this taxon had short lifespans lasting around a month.[34] A study Sr/Ca and Ba/Ca ratios of a population of conodonts from a carbonate platform from the Silurian of Sweden found that the different conodont species and genera likely occupied different trophic niches.[33]

Some species of the genus Panderodus have been speculated to be venomous, based on grooves found on some elements.[35]

Classification and phylogeny

[edit]Affinities

[edit]As of 2012[update], scientists classify the conodonts in the phylum Chordata on the basis of their fins with fin rays, chevron-shaped muscles and notochord.[36]

Milsom and Rigby envision them as vertebrates similar in appearance to modern hagfish and lampreys,[37] and phylogenetic analysis suggests they are more derived than either of these groups.[9] However, this analysis comes with one caveat: the earliest conodont-like fossils, the protoconodonts, appear to form a distinct clade from the later paraconodonts and euconodonts. Protoconodonts are probably not relatives of true conodonts, but likely represent a stem group to Chaetognatha, an unrelated phylum that includes arrow worms.[38]

Moreover, some analyses do not regard conodonts as either vertebrates or craniates, because they lack the main characteristics of these groups.[39] More recently it has been proposed that conodonts may be stem-cyclostomes, more closely related to hagfish and lampreys than to jawed vertebrates.[40]

Ingroup relations

[edit]Individual conodont elements are difficult to classify in a consistent manner, but an increasing number of conodont species are now known from multi-element assemblages, which offer more data to infer how different conodont lineages are related to each other. The following is a simplified cladogram based on Sweet and Donoghue (2001),[10] which summarized previous work by Sweet (1988)[8] and Donoghue et al. (2000):[9]

Only a few studies approach the question of conodont ingroup relationships from a cladistic perspective, as informed by phylogenetic analyses. One of the broadest studies of this nature was the analysis of Donoghue et al. (2008), which focused on "complex" conodonts (Prioniodontida and other descendant groups):[11]

Evolutionary history

[edit]

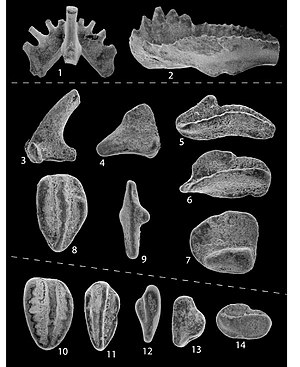

1. Kladognathus sp., Sa element, posterior view, X140 2. Cavusgnathus unicornis, gamma morphotype, Pa element, lateral view, X140

3–9. Conodonts from the uppermost Loyalhanna Limestone Member of the Mauch Chunk Formation, Keystone quarry, Pa. This collection (93RS–79b) is from the upper 10 cm of the Loyalhanna Member. Note the highly abraded and reworked aeolian forms.

3, 4. Kladognathus sp., Sa element, lateral views, X140

5. Cavusgnathus unicornis, alpha morphotype, Pa element, lateral view, X140

6, 7. Cavusgnathus sp., Pa element, lateral view, X140

8. Polygnathus sp., Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian to Early Mississippian morphotype, X140

9. Gnathodus texanus?, Pa element, upper view, X140

10–14. Conodonts from the basal 20 cm of the Loyalhanna Limestone Member of the Mauch Chunk Formation, Keystone quarry, Pa. (93RS–79a), and Westernport, Md. (93RS–67), note the highly abraded and reworked aeolian forms

10. Polygnathus sp., Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian to Early Mississippian morphotype, 93RS–79a, X140

11. Polygnathus sp., Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian to Early Mississippian morphotype, 93RS–67, X140

12. Gnathodus sp., Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian(?) through Mississippian morphotype, 93RS–67, X140

13. Kladognathus sp., M element, lateral views, 93RS–67, X140

14. Cavusgnathus sp., Pa element, lateral view, 93RS–67, X140

The earliest fossils of conodonts are known from the Cambrian period. Conodonts extensively diversified during the early Ordovician, reaching their apex of diversity during the middle part of the period, and experienced a sharp decline during the late Ordovician and Silurian, before reaching another peak of diversity during the mid-late Devonian. Conodont diversity declined during the Carboniferous, with an extinction event at the end of the middle Tournaisian[41] and a prolonged period of significant loss of diversity during the Pennsylvanian.[42][43] Only a handful of conodont genera were present during the Permian, though diversity increased after the P-T extinction during the Early Triassic.

Diversity continued to decline during the Middle and Late Triassic, culminating in their extinction soon after the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Much of their diversity during the Paleozoic was likely controlled by sea levels and temperature, with the major declines during the Late Ordovician and Late Carboniferous due to cooler temperatures, especially glacial events and associated marine regressions which reduced continental shelf area. However, their final demise is more likely related to biotic interactions, perhaps competition with new Mesozoic taxa.[44]

Taxonomy

[edit]Conodonta taxonomy based on Sweet (1988),[8] Sweet & Donoghue (2001),[10] and Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.[45][clarification needed]

- Class Conodonta Pander, 1856 [Conodontophorida Eichenberg, 1930; "euconodonts" Bengtson, 1976]

- Cavidonti Sweet, 1988

- Order Belodellida? Sweet, 1988

- Ansellidae? Fåhraeus & Hunter, 1985

- Belodellidae Khodalevich & Tschernich, 1973

- Dapsilodontidae? Sweet, 1988

- Order Proconodontida Sweet, 1988

- Cordylodontidae Lindström, 1970

- Fryxellodontidae Miller, 1981

- Pseudooneotodidae? Wang & Aldridge, 2010

- Proconodontidae Lindström, 1970

- Pygodontidae? Bergstrom, 1981

- Order Belodellida? Sweet, 1988

- Conodonti Pander, 1856 non Branson, 1938

- Order Protopanderodontida Sweet, 1988

- Acanthodontidae Lindström, 1970

- Clavohamulidae Lindström, 1970

- Drepanoistodontidae? Fåhraeus, 1978 [Distacodontidae Bassler, 1925]

- Protopanderodontidae Lindström, 1970 [Scolopodontidae Bergström, 1981; Oneotodontidae Miller, 1981; Teridontidae Miller, 1981]

- Serratognathidae? Zhen et al., 2009

- Strachanognathidae? Bergström, 1981 [Cornuodontidae Stouge, 1984]

- Order Panderodontida Sweet, 1988

- Panderodontidae Lindström, 1970

- Order Prioniodontida Dzik, 1976 (paraphyletic)

- Acodontidae? Dzik, 1993 [Tripodontinae Sweet, 1988]

- Cahabagnathidae? Stouge & Bagnoli 1999

- Distacodontidae? Bassler, 1925 emend. Ulrich & Bassler, 1926 [Drepanodontinae Fåhraeus & Nowlan, 1978; Lonchodininae Hass, 1959]

- Gamachignathidae? Wang & Aldridge, 2010

- Jablonnodontidae? Dzik, 2006

- Nurrellidae? Pomešano-Cherchi, 1967

- Paracordylodontidae? Bergström, 1981

- Playfordiidae? Dzik, 2002

- Ulrichodinidae? Bergström, 1981

- Rossodus Repetski & Ethington, 1983

- Multioistodontidae Harris, 1964 [Dischidognathidae]

- Oistodontidae Lindström, 1970 [Juanognathidae Bergström, 1981]

- Periodontidae Lindström, 1970

- Rhipidognathidae Lindström, 1970 sensu Sweet, 1988

- Prioniodontidae Bassler, 1925

- Phragmodontidae Bergström, 1981 [Cyrtoniodontinae Hass, 1959]

- Plectodinidae Sweet, 1988

- Pygodontidae? Bergstrom, 1981

- Icriodontacea

- Balognathidae (Hass, 1959)

- Polyplacognathidae Bergström, 1981

- Distomodontidae Klapper, 1981

- Icriodellidae Sweet, 1988

- Icriodontidae Müller & Müller, 1957

- Order Prioniodinida Sweet, 1988

- Oepikodontidae? Bergström, 1981

- Xaniognathidae? Sweet, 1981

- Chirognathidae Branson & Mehl, 1944

- Prioniodinidae Bassler, 1925 [Hibbardellidae Mueller, 1956]

- Bactrognathidae Lindström, 1970

- Ellisoniidae Clark, 1972

- Gondolellidae Lindström, 1970

- Order Ozarkodinida Dzik, 1976 [Polygnathida]

- Anchignathodontidae? Clark, 1972

- Archeognathidae? Miller, 1969

- Belodontidae? Huddle, 1934

- Coleodontidae? Branson & Mehl, 1944 [Hibbardellidae Müller, 1956; Loxodontidae]

- Eognathodontidae? Bardashev, Weddige & Ziegler, 2002

- Francodinidae? Dzik, 2006

- Gladigondolellidae? (Hirsch, 1994) [Sephardiellinae Plasencia, Hirsch & Márquez-Aliaga, 2007; Neogondolellinae Hirsch, 1994; Cornudininae Orchard, 2005; Epigondolellinae Orchard, 2005; Marquezellinae Plasencia et al., 2018; Paragondolellinae Orchard, 2005; Pseudofurnishiidae Ramovs, 1977]

- Iowagnathidae? Liu et al., 2017

- Novispathodontidae? (Orchard, 2005)

- Trucherognathidae? Branson & Mehl, 1944

- Vjalovognathidae? Shen, Yuan & Henderson, 2015

- Wapitiodontidae? Orchard, 2005

- Cryptotaxidae Klapper & Philip, 1971

- Spathognathodontidae Hass, 1959 [Ozarkodinidae Dzik, 1976]

- Pterospathodontidae Cooper, 1977 [Carniodontidae]

- Kockelellidae Klapper, 1981 [Caenodontontidae]

- Polygnathidae Bassler, 1925 [?Eopolygnathidae Bardashev, Weddige & Ziegler, 2002]

- Palmatolepidae Sweet, 1988

- Hindeodontidae (Hass, 1959)

- Elictognathidae Austin & Rhodes, 1981

- Gnathodontidae Sweet, 1988

- Idiognathodontidae Harris & Hollingsworth, 1933

- Mestognathidae Austin & Rhodes, 1981

- Cavusgnathidae Austin & Rhodes, 1981

- Sweetognathidae Ritter, 1986

- Order Protopanderodontida Sweet, 1988

- Cavidonti Sweet, 1988

See also

[edit]- Timeline of the evolutionary history of life

- Micropaleontology

- List of conodont genera

- Conodont biostratigraphy

- Conodont alteration index

References

[edit]- ^ a b Eichenberg, W. (1930). "Conodonten aus dem Culm des Harzes". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 12 (3–4): 177–182. doi:10.1007/BF03044446. S2CID 129519805.

- ^ Sweet, Walter C.; Cooper, Barry J. (December 2008). "C.H. Pander's introduction to conodonts, 1856". Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Jan Zalasiewicz and Sarah Gabbott (Jun 5, 1999). "The quick and the dead". New Scientist.

- ^ a b Fåhraeus, Lars E. (1983). "Phylum Conodonta Pander, 1856 and Nomenclatural Priority". Systematic Zoology. 32 (4): 455–459. doi:10.2307/2413175. JSTOR 2413175.

- ^ a b Bengtson, Stefan (1976). "The structure of some Middle Cambrian conodonts, and the early evolution of conodont structure and function". Lethaia. 9 (2): 185–206. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1976.tb00966.x. ISSN 0024-1164.

- ^ Clark, David L. (1981). "Chapter 3: Systematic Descriptions". In Moore, Raymond C.; Robison, R.A. (eds.). Part W, Miscellanea, Supplement 2: Conodonta. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Boulder, Colorado; Lawrence, Kansas: Geological Society of America; University of Kansas. pp. 111–180. ISBN 0-8137-3028-7.

- ^ Fåhraeus, Lars E. (1984). "A critical look at the Treatise family-group classification of Conodonta: an exercise in eclecticism". Lethaia. 17 (4): 293–305. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1984.tb00675.x. ISSN 0024-1164.

- ^ a b c Sweet, W. C. (1988). "The Conodonta: morphology, taxonomy, paleoecology and evolutionary history of a long-extinct animal phylum". Oxford Monographs on Geology and Geophysics (10): 1–211. ISBN 978-0-19-504352-5.

- ^ a b c d e Donoghue, P.C.J.; Forey, P.L.; Aldridge, R.J. (2000). "Conodont affinity and chordate phylogeny". Biological Reviews. 75 (2): 191–251. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00045.x. PMID 10881388. S2CID 22803015.

- ^ a b c d Sweet, W. C.; Donoghue, P. C. J. (2001). "Conodonts: Past, Present, Future" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 75 (6): 1174–1184. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<1174:CPPF>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 53395896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-30.

- ^ a b c Donoghue, Philip C. J.; Purnell, Mark A.; Aldridge, Richard J.; Zhang, Shunxin (2008-01-01). "The interrelationships of 'complex' conodonts (Vertebrata)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 119–153. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002234. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ MIRACLE. "Conodonts". Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Briggs, D. E. G.; Clarkson, E. N. K.; Aldridge, R. J. (1983). "The conodont animal". Lethaia. 16 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1983.tb01993.x.

- ^ Trotter, Julie A. (2006). "Chemical systematics of conodont apatite determined by laser ablation ICPMS". Chemical Geology. 233 (3–4): 196–216. Bibcode:2006ChGeo.233..196T. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.03.004.

- ^ Jeppsson, Lennart; Anehus, Rikard (1995). "A Buffered Formic Acid Technique for Conodont Extraction". Journal of Paleontology. 69 (4): 790–794. doi:10.1017/s0022336000035319. JSTOR 1306313. S2CID 131850219.

- ^ Green, Owen R. (2001). "Extraction Techniques for Phosphatic Fossils". A Manual of Practical Laboratory and Field Techniques in Palaeobiology. pp. 318–330. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-0581-3_27. ISBN 978-90-481-4013-8.

- ^ Quinton, Page C. (2016). "Effects of extraction protocols on the oxygen isotope composition of conodont elements". Chemical Geology. 431: 36–43. Bibcode:2016ChGeo.431...36Q. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.03.023.

- ^ Bergström, S. M.; Carnes, J. B.; Ethington, R. L.; Votaw, R. B.; Wigley, P. B. (1974). "Appalachignathus, a New Multielement Conodont Genus from the Middle Ordovician of North America". Journal of Paleontology. 48 (2): 227–235. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<1174:CPPF>2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 1303249. S2CID 53395896.

- ^ Schmidt, Hermann (1934). "Conodonten-Funde in ursprünglichem Zusammenhang". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 16 (1–2): 76–85. doi:10.1007/BF03041668. S2CID 128496416.

- ^ Harold W. Scott, "The Zoological Relationships of the Conodonts. Journal of Paleontology, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Dec., 1934), pages 448-455 (Stable URL)

- ^ Scott, Harold W. (1942). "Conodont Assemblages from the Heath Formation, Montana". Journal of Paleontology. 16 (3): 293–300. JSTOR 1298905.

- ^ Dunn, David L. (1965). "Late Mississippian conodonts from the Bird Spring Formation in Nevada". Journal of Paleontology. 39: 6. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Barnes, Christopher R. (1967). "A Questionable Natural Conodont Assemblage from Middle Ordovician Limestone, Ottawa, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 41 (6): 1557–1560. JSTOR 1302203.

- ^ Purnell, M. A.; Donoghue, P. C. (1997). "Architecture and functional morphology of the skeletal apparatus of ozarkodinid conodonts". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 352 (1361): 1545–1564. Bibcode:1997RSPTB.352.1545P. doi:10.1098/rstb.1997.0141. PMC 1692076.

- ^ Conway Morris, Simon (1990-04-12). "Typhloesus wellsi (Melton and Scott, 1973), a bizarre metazoan from the Carboniferous of Montana, U. S. A". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences. 327 (1242): 595–624. Bibcode:1990RSPTB.327..595M. doi:10.1098/rstb.1990.0102.

- ^ a b Conway Morris, Simon; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2022). "A possible home for a bizarre Carboniferous animal: Is Typhloesus a pelagic gastropod?". Biology Letters. 18 (9). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2022.0179. PMC 9489302. PMID 36126687.

- ^ a b c Murdock, Duncan J. E.; Smith, M. Paul (2021). Sansom, Robert (ed.). "Panderodus from the Waukesha Lagerstätte of Wisconsin, USA: a primitive macrophagous vertebrate predator". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (4): 1977–1993. doi:10.1002/spp2.1389. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 237769553.

- ^ a b c d Gabbott, S.E.; R. J. Aldridge; J. N. Theron (1995). "A giant conodont with preserved muscle tissue from the Upper Ordovician of South Africa". Nature. 374 (6525): 800–803. Bibcode:1995Natur.374..800G. doi:10.1038/374800a0. S2CID 4342260.

- ^ von Bitter, Peter H.; Purnell, Mark A.; Tetreault, Denis K.; Stott, Christopher A. (2007). "Eramosa Lagerstätte—Exceptionally preserved soft-bodied biotas with shallow-marine shelly and bioturbating organisms (Silurian, Ontario, Canada)". Geology. 35 (10): 879. Bibcode:2007Geo....35..879V. doi:10.1130/g23894a.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Takahashi, Satoshi; Yamakita, Satoshi; Suzuki, Noritoshi (2019-06-15). "Natural assemblages of the conodont Clarkina in lowermost Triassic deep-sea black claystone from northeastern Japan, with probable soft-tissue impressions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 524: 212–229. Bibcode:2019PPP...524..212T. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.03.034. ISSN 0031-0182. S2CID 134664744.

- ^ Foster, John (2014-06-06). Cambrian Ocean World: Ancient Sea Life of North America. Indiana University Press. pp. 300–301. ISBN 978-0-253-01188-6.

- ^ Purnell, Mark A. (1 April 1993). "Feeding mechanisms in conodonts and the function of the earliest vertebrate hard tissues". Geology. 21 (4): 375–377. Bibcode:1993Geo....21..375P. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0375:FMICAT>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Terrill, David F.; Jarochowska, Emilia; Henderson, Charles M.; Shirley, Bryan; Bremer, Oskar (2022-04-08). "Sr/Ca and Ba/Ca ratios support trophic partitioning within a Silurian conodont community from Gotland, Sweden". Paleobiology. 48 (4): 601–621. doi:10.1017/pab.2022.9. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 248062641.

- ^ Świś, Przemysław (2019). "Population dynamics of the Late Devonian conodont Alternognathus calibrated in days". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology: 1–9. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1427088. S2CID 89835464.

- ^ Szaniawski, Hubert (December 2009). "The Earliest Known Venomous Animals Recognized Among Conodonts". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 54 (4): 669–676. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0045.

- ^ Briggs, D. (May 1992). "Conodonts: a major extinct group added to the vertebrates". Science. 256 (5061): 1285–1286. Bibcode:1992Sci...256.1285B. doi:10.1126/science.1598571. PMID 1598571.

- ^ Milsom, Clare; Rigby, Sue (2004). "Vertebrates". Fossils at a Glance. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-632-06047-4.

- ^ Szaniawski, H. (2002). "New evidence for the protoconodont origin of chaetognaths" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 47 (3): 405.

- ^ Turner, S., Burrow, C.J., Schultze, H.P., Blieck, A., Reif, W.E., Rexroad, C.B., Bultynck, P., Nowlan, G.S.; Burrow; Schultze; Blieck; Reif; Rexroad; Bultynck; Nowlan (2010). "False teeth: conodont-vertebrate phylogenetic relationships revisited" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 32 (4): 545–594. doi:10.5252/g2010n4a1. S2CID 86599352. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miyashita, Tetsuto; Coates, Michael I.; Farrar, Robert; Larson, Peter; Manning, Phillip L.; Wogelius, Roy A.; Edwards, Nicholas P.; Anné, Jennifer; Bergmann, Uwe; Palmer, A. Richard; Currie, Philip J. (2019-02-05). "Hagfish from the Cretaceous Tethys Sea and a reconciliation of the morphological–molecular conflict in early vertebrate phylogeny". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (6): 2146–2151. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.2146M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1814794116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6369785. PMID 30670644.

- ^ Zhuravlev, Andrey V.; Plotitsyn, Artem N. (18 January 2022). "The middle–late Tournaisian crisis in conodont diversity: a comparison between Northeast Laurussia and Northeast Siberia". Palaeoworld. 31 (4): 633–645. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2022.01.001. S2CID 246060690. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ Shi, Yukun; Wang, Xiangdong; Fan, Junxuan; Huang, Hao; Xu, Huiqing; Zhao, Yingying; Shen, Shuzhong (September 2021). "Carboniferous-earliest Permian marine biodiversification event (CPBE) during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age". Earth-Science Reviews. 220: 103699. Bibcode:2021ESRv..22003699S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103699. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Sepkoski, J. J. (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 363: 1–560.

- ^ Ginot, Samuel; Goudemand, Nicolas (December 2020). "Global climate changes account for the main trends of conodont diversity but not for their final demise". Global and Planetary Change. 195: 103325. Bibcode:2020GPC...19503325G. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103325. S2CID 225005180.

- ^ Mikko's Phylogeny Archive [1] Haaramo, Mikko (2007). "Conodonta - conodonts". Retrieved 2015-12-30.

Further reading

[edit]- Aldridge, R. J.; Briggs, D. E. G.; Smith, M. Paul; Clarkson, E. N. K.; Clark, N. D. L. (1993). "The anatomy of conodonts". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 340 (1294): 405–421. doi:10.1098/rstb.1993.0082.

- Aldridge, R. J.; Purnell, M. A. (1996). "The conodont controversies". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 11 (11): 463–468. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10048-3. PMID 21237922.

- Donoghue, P. C. J.; Forey, P. L.; Aldridge, R. J. (2000). "Conodont affinity and chordate phylogeny". Biological Reviews. 75 (2): 191–251. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00045.x. PMID 10881388. S2CID 22803015.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1985). "Reducing Riddles". In The Flamingo's Smile, 245-260. New York, W.W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0-393-30375-6.

- Janvier, P (1997). "Euconodonta". The tree of life web project. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- Knell, Simon J. The Great Fossil Enigma: The Search for the Conodont Animal (Indiana University Press; 2012) 440 pages

- Sweet, Walter (1988). The Conodonta: morphology, taxonomy, paleoecology, and evolutionary history of a long-extinct animal phylum. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Sweet, W. C.; Donoghue, P. C. J. (2001). "Conodonts: past, present and future" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 75 (6): 1174–1184. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<1174:CPPF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 53395896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-30.

- Lindström, Maurits (1970). "A suprageneric taxonomy of the conodonts". Lethaia. 3 (4): 427–445. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1970.tb00834.x.

External links

[edit]- Mark Purnell. "An oblique anterior view of a model of the apparatus of the Pennsylvanian conodont Idiognathodus".

- "'The Jaws That Catch': an Introduction to the Conodonta". Palæos. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Jim Davison (2002-10-15). "Ordovician conodonts". Retrieved 2009-07-07.