Asiatic lion

| Asiatic lion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male Asiatic lion in Gir National Park | |

| |

| Female with cub | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. leo |

| Subspecies: | P. l. leo |

| Population: | Asiatic lion |

| |

| Current range of the Asiatic lion | |

The Asiatic lion is a lion population of the subspecies Panthera leo leo. Until the 19th century, it occurred in Saudi Arabia, eastern Turkey, Iran, Mesopotamia, and from east of the Indus River in Pakistan to the Bengal region and the Narmada River in Central India. Since the turn of the 20th century, its range has been restricted to Gir National Park and the surrounding areas in the Indian state of Gujarat. The first scientific description of the Asiatic lion was published in 1826 by the Austrian zoologist Johann N. Meyer, who named it Felis leo persicus.

The population has steadily increased since 2010. In 2015, the 14th Asiatic Lion Census was conducted over an area of about 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi); the lion population was estimated at 523 individuals, and in 2017 at 650 individuals.

Taxonomy

[edit]Felis leo persicus was the scientific name proposed by Johann N. Meyer in 1826 who described an Asiatic lion skin from Persia.[2] In the 19th century, several zoologists described lion zoological specimen from other parts of Asia that used to be considered synonyms of P. l. persica:[3]

- Felis leo bengalensis proposed by Edward Turner Bennett in 1829 was a lion kept in the menagerie of the Tower of London. Bennett's essay contains a drawing titled 'Bengal lion'.[4]

- Felis leo goojratensis proposed by Walter Smee in 1833 was based on two skins of maneless lions from Gujarat that Smee exhibited in a meeting of the Zoological Society of London.[5]

- Leo asiaticus proposed by Sir William Jardine, 7th Baronet in 1834 was a lion from India.[6]

- Felis leo indicus proposed by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1843 was based on an Asiatic lion skull.[7]

In 2017, the Asiatic lion was subsumed to P. l. leo due to close morphological and molecular genetic similarities with Barbary lion specimens.[8][9] However, several scientists continue using P. l. persica for the Asiatic lion.[10][11][12][13][14][15] A standardised haplogroup phylogeny supports that the Asiatic lion is not a distinct subspecies, and that it represents a haplogroup of the northern P. l. leo.[16]

Evolution

[edit]Lions first left Africa at least 700,000 years ago, giving rise to the Eurasian Panthera fossilis which later evolved into Panthera spelaea (commonly known as the cave lion), which became extinct around 14,000 years ago. Genetic analysis of P. spelaea indicates that it represented a distinct species from the modern lion that diverged from them around 500,000 years ago and unrelated to modern Asian lions.[17] Pleistocene fossils assigned as belonging or probably belonging to the modern lion have been reported from several sites in the Middle East, such as Shishan Marsh in the Azraq Basin, Jordan, dating to around 250,000 years ago,[18] and Wezmeh Cave in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran, dating to around 70–10,000 years ago,[19] with other reports from Pleistocene deposits in Nadaouiyeh Ain Askar and Douara Cave, Syria.[18] In 1976, fossil lion remains were reported from Pleistocene deposits in West Bengal.[20] A fossil carnassial excavated from Batadomba Cave indicates that lions inhabited Sri Lanka during the Late Pleistocene. This population may have become extinct around 39,000 years ago, before the arrival of humans in Sri Lanka.[21]

Phylogeography

[edit]Results of a phylogeographic analysis based on mtDNA sequences of lions from across the global range, including now extinct populations like Barbary lions, indicates that sub-Saharan African lions are phylogenetically basal to all modern lions. These findings support an African origin of modern lion evolution with a probable centre in East and Southern Africa. It is likely that lions migrated from there to West Africa, eastern North Africa and via the periphery of the Arabian Peninsula into Turkey, southern Europe and northern India during the last 20,000 years. The Sahara, Congolian rainforests and the Great Rift Valley are natural barriers to lion dispersal.[22]

Genetic markers of 357 samples from captive and wild lions from Africa and India were examined. Results indicate four lineages of lion populations: one in Central and North Africa to Asia, one in Kenya, one in Southern Africa, and one in Southern and East Africa; the first wave of lion expansion probably occurred about 118,000 years ago from East Africa into West Asia, and the second wave in the late Pleistocene or early Holocene periods from Southern Africa towards East Africa.[23] The Asiatic lion is genetically closer to North and West African lions than to the group comprising East and Southern African lions. The two groups probably diverged about 186,000–128,000 years ago. It is thought that the Asiatic lion remained connected to North and Central African lions until gene flow was interrupted due to extinction of lions in Western Eurasia and the Middle East during the Holocene.[24][25]

Asiatic lions are less genetically diverse than African lions, which may be the result of a founder effect in the recent history of the remnant population in the Gir Forest.[26]

Characteristics

[edit]The Asiatic lion's fur ranges in colour from ruddy-tawny, heavily speckled with black, to sandy or buffish grey, sometimes with a silvery sheen in certain lighting. Males have only moderate mane growth at the top of the head, so that their ears are always visible. The mane is scanty on the cheeks and throat, where it is only 10 cm (4 in) long. About half of Asiatic lions' skulls from the Gir forest have divided infraorbital foramina, whereas African lions have only one foramen on either side. The sagittal crest is more strongly developed, and the post-orbital area is shorter than in African lions. Skull length in adult males ranges from 330–340 mm (13–13+1⁄2 in), and in females, from 292–302 mm (11+1⁄2–11+7⁄8 in). It differs from the African lion by a larger tail tuft and less inflated auditory bullae.[3] The most striking morphological character of the Asiatic lion is a longitudinal fold of skin running along its belly.[27]

Males have a shoulder height of up to 107–120 cm (42–47 in), and females of 80–107 cm (31+1⁄2–42 in).[28] Two lions in Gir Forest measured 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in) from head to body with a 0.79–0.89 m (31–35 in) long tail of and total lengths of 2.82–2.87 m (9 ft 3 in – 9 ft 5 in). The Gir lion is similar in size to the Central African lion,[3] and smaller than large African lions.[29] An adult male Asiatic lion weighs 160.1 kg (353 lb) on average with the limit being 190 kg (420 lb); a wild female weighs 100 to 130 kg (220 to 285 lb).[30][31][1]

Manes

[edit]

Colour and development of manes in male lions varies between regions, among populations and with age of lions.[32] In general, the Asiatic lion differs from the African lion by a less developed mane.[3] The manes of most lions in ancient Greece and Asia Minor were also less developed and did not extend to below the belly, sides or ulnas. Lions with such smaller manes were also known in the Syrian region, Arabian Peninsula and Egypt.[33][34]

Exceptionally sized lions

[edit]The confirmed record total length of a male Asiatic lion is 2.92 m (9 ft 7 in), including the tail.[35] Emperor Jahangir allegedly speared a lion in the 1620s that measured 3.10 m (10 ft 2 in) and weighed 306 kg (675 lb).[36] In 1841, English traveller Austen Henry Layard accompanied hunters in Khuzestan, Iran, and sighted a lion which "had done much damage in the plain of Ram Hormuz," before one of his companions killed it. He described it as being "unusually large and of very dark brown colour", with some parts of its body being almost black.[37] In 1935, a British admiral claimed to have sighted a maneless lion near Quetta in Pakistan. He wrote "It was a large lion, very stocky, light tawny in colour, and I may say that no one of us three had the slightest doubt of what we had seen until, on our arrival at Quetta, many officers expressed doubts as to its identity, or to the possibility of there being a lion in the district."[38]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

In Saurashtra's Gir Forest, an area of 1,412.1 km2 (545.2 sq mi) was declared as a sanctuary for Asiatic lion conservation in 1965. This sanctuary and the surrounding areas are the only habitats supporting the Asiatic lion.[39] After 1965, a national park was established covering an area of 258.71 km2 (99.89 sq mi) where human activity is not allowed. In the surrounding sanctuary only Maldharis have the right to take their livestock for grazing.[40]

Lions inhabit remnant forest habitats in the two hill systems of Gir and Girnar that comprise Gujarat's largest tracts of tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, thorny forest and savanna, and provide valuable habitat for a diverse flora and fauna. Five protected areas currently exist to protect the Asiatic lion: Gir Sanctuary, Gir National Park, Pania Sanctuary, Mitiyala Sanctuary, and Girnar Sanctuary. The first three protected areas form the Gir Conservation Area, a 1,452 km2 (561 sq mi) large forest block that represents the core habitat of the lion population. The other two sanctuaries Mitiyala and Girnar protect satellite areas within dispersal distance of the Gir Conservation Area. An additional sanctuary is being established in the nearby Barda Wildlife Sanctuary to serve as an alternative home for lions.[39] The drier eastern part is vegetated with acacia thorn savanna and receives about 650 mm (26 in) annual rainfall; rainfall in the west is higher at about 1,000 mm (39 in) per year.[30]

The lion population recovered from the brink of extinction to 411 individuals by 2010. In that year, approximately 105 lions lived outside the Gir forest, representing a quarter of the entire lion population. Dispersing sub-adults established new territories outside their natal prides, and as a result the satellite lion population has been increasing since 1995.[39] By 2015, the total population had grown to an estimated 523 individuals, inhabiting an area of 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) in the Saurashtra region., comprising 109 adult males, 201 adult females and 213 cubs.[41][10][42] The Asiatic Lion Census conducted in 2017 revealed about 650 individuals.[43]

By 2020, at least six satellite populations had spread to eight districts in Gujarat and live in human-dominated areas outside the protected area network.[44] 104 lived near the coastline. Lions living along the coast, as well as those between the coastline and the Gir forest, have larger individual ranges.[45]

Former range

[edit]During the Holocene, from around 6,500 years ago and possibly as early as 8,000 years ago, modern lions colonised Southeast Europe (including modern Bulgaria and Greece in the Balkans), as well as parts of Central Europe like Hungary and Ukraine in Eastern Europe. Analysis of remains of these European lions suggests that they do not differ from those of modern Asiatic lions, and they should be assigned to this population.[46] Historical records suggest that lions became extinct in Europe during Classical antiquity,[47] though it has been suggested that they may have survived as late as the Middle Ages in Ukraine.[46]

The Asiatic lion used to occur in Arabia, the Levant, Mesopotamia and Baluchistan.[3] In South Caucasia, it was known since the Holocene and became extinct in the 10th century. Until the middle of the 19th century, it survived in regions adjoining Mesopotamia and Syria, and was still sighted in the upper reaches of the Euphrates River in the early 1870s.[33][49] By the late 19th century, it had become extinct in Saudi Arabia and Turkey.[50][51] The last known lion in Iraq was killed on the lower Tigris in 1918.[52]

Historical records in Iran indicate that it ranged from the Khuzestan Plain to Fars province at elevations below 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in steppe vegetation and pistachio-almond woodlands.[53] It was widespread in the country, but in the 1870s, it was sighted only on the western slopes of the Zagros Mountains, and in the forest regions south of Shiraz.[33] It served as the national emblem and appeared on the country's flag. Some of the country's last lions were sighted in 1941 between Shiraz and Jahrom in Fars province, and in 1942, a lion was spotted about 65 km (40 mi) northwest of Dezful.[54] In 1944, the corpse of a lioness was found on the banks of the Karun River in Iran's Khuzestan province.[55][56]

In India, the Asiatic lion occurred in Sind, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, Bihar and eastward as far as Palamau and Rewa, Madhya Pradesh in the early 19th century.[57][37] It once ranged to Bangladesh in the east and up to Narmada River in the south.[37] Because of the lion's restricted distribution in India, Reginald Innes Pocock assumed that it arrived from Europe, entering southwestern Asia through Balochistan only recently, before humans started limiting its dispersal in the country. The advent and increasing availability of firearms led to its local extirpation over large areas.[3] Heavy hunting by British colonial officers and Indian rulers caused a steady and marked decline of lion numbers in the country.[40] Lions were exterminated in Palamau by 1814, in Baroda State, Hariana and Ahmedabad district in the 1830s, in Kot Diji and Damoh district in the 1840s. During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, a British officer shot 300 lions. The last lions of Gwalior and Rewah were shot in the 1860s. One lion was killed near Allahabad in 1866.[57] The last lion of Mount Abu in Rajasthan was spotted in 1872.[58] By the late 1870s, lions were extinct in Rajasthan.[37] By 1880, no lion survived in Guna, Deesa and Palanpur districts, and only about a dozen lions were left in Junagadh district. By the turn of the century, the Gir Forest held the only Asiatic lion population in India, which was protected by the Nawab of Junagarh in his private hunting grounds.[3][37]

Ecology and behaviour

[edit]Male Asiatic lions are solitary, or associate with up to three males, forming a loose pride. Pairs of males rest, hunt and feed together, and display marking behaviour at the same sites. Females associate with up to twelve other females, forming a stronger pride together with their cubs. They share large carcasses among each other, but seldom with males. Female and male lions usually associate only for a few days when mating, but rarely live and feed together.[59][60]

Results of a radio telemetry study indicate that annual home ranges of male lions vary from 144 to 230 km2 (56 to 89 sq mi) in dry and wet seasons. Home ranges of females are smaller, varying between 67 and 85 km2 (26 and 33 sq mi).[61] During hot and dry seasons, they favour densely vegetated and shady riverine habitats, where prey species also congregate.[62][63]

Coalitions of males defend home ranges containing one or more female prides.[64] Together, they hold a territory for a longer time than single lions. Males in coalitions of three to four individuals exhibit a pronounced hierarchy with one male dominating the others.[65]

The lions in Gir National Park are active at twilight and by night, showing a high temporal overlap with sambar (Rusa unicolor), wild boar (Sus scrofa) and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus).[66]

Feeding ecology

[edit]In general, lions prefer large prey species within a weight range of 190 to 550 kg (420 to 1,210 lb), irrespective of their availability.[67] Domestic cattle have historically been a major component of the Asiatic lions' diet in the Gir Forest.[3] Inside Gir Forest National Park, lions predominantly kill chital (Axis axis), sambar deer, nilgai, cattle (Bos taurus), domestic water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), and less frequently wild boar.[61] They most commonly kill chital, which weighs only around 50 kg (110 lb).[64] They prey on sambar deer when the latter descend from the hills during summer. Outside the protected area where wild prey species do not occur, lions prey on water buffalo and cattle, and rarely on dromedary (Camelus dromedarius). They generally kill most prey less than 100 m (330 ft) away from water bodies, charge prey from close range and drag carcasses into dense cover.[61] They regularly visit specific sites within the protected area to scavenge on dead livestock dumped by Maldhari livestock herders.[68] During dry, hot months, they also prey on mugger crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris) on the banks of Kamleshwar Dam.[56]: 148

In 1974, the Forest Department estimated the wild ungulate population at 9,650 individuals. In the following decades, the wild ungulate population has grown consistently to 31,490 in 1990 and 64,850 in 2010, including 52,490 chital, 4,440 wild boar, 4,000 sambar, 2,890 nilgai, 740 chinkara (Gazella bennetti), and 290 four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis). In contrast, populations of domestic buffalo and cattle declined following resettlement, largely due to direct removal of resident livestock from the Gir Conservation Area. The population of 24,250 domestic livestock in the 1970s declined to 12,500 by the mid-1980s, but increased to 23,440 animals in 2010. Following changes in both predator and prey communities, Asiatic lions shifted their predation patterns. Today, very few livestock kills occur within the sanctuary, and instead most occur in peripheral villages. Depredation records indicate that in and around the Gir Forest, lions killed on average 2,023 livestock annually between 2005 and 2009, and an additional 696 individuals in satellite areas.[39]

Dominant males consume about 47% more from kills than their coalition partners. Aggression between partners increases when coalitions are large, but kills are small.[65]

Reproduction

[edit]Asiatic lions mate foremost between October and November.[69] Mating lasts three to six days. During these days, they usually do not hunt, but only drink water. Gestation lasts about 110 days. Litters comprise one to four cubs.[70] The average interval between births is 24 months, unless cubs die due to infanticide by adult males or because of diseases and injuries. Cubs become independent at the age of about two years. Subadult males leave their natal pride latest at the age of three years and become nomads until they establish their own territory.[60] Dominant males mate more frequently than their coalition partners. During a study carried out between December 2012 and December 2016, three females were observed switching mating partners in favour of the dominant male.[65] Monitoring of more than 70 mating events showed that females mated with males of several rivaling prides that shared their home ranges, and that these males were tolerant toward the same cubs. Only new males that entered the female territories killed unfamiliar cubs. Young females mated foremost with males within their home ranges. Older females selected males at the periphery of their home ranges.[71]

Threats

[edit]

The Asiatic lion currently exists as a single subpopulation, and is thus vulnerable to extinction from unpredictable events, such as an epidemic or large forest fire. There are indications of poaching incidents in recent years, as well as reports that organized poacher gangs have switched attention from local Bengal tigers to the Gujarat lions. There have also been a number of drowning incidents, after lions fell into wells.[1]

Prior to the resettlement of Maldharis, the Gir forest was heavily degraded and used by livestock, which competed with and restricted the population sizes of native ungulates. Various studies reveal tremendous habitat recovery and increases in wild ungulate populations following the resettlement of Maldharis since the 1970s.[39]

Nearly 25 lions in the vicinity of Gir Forest were found dead in October 2018. Four of them had died because of canine distemper virus, the same virus that had also killed several lions in the Serengeti.[72][73]

Conflicts with humans

[edit]Since the mid-1990s, the Asiatic lion population has increased to an extent that by 2015, about a third resided outside the protected area. Hence, conflict between local residents and wildlife also increased. Local people protect their crops from nilgai, wild boar, and other herbivores by using electrical fences that are powered with high voltage. Some consider the presence of predators a benefit, as they keep the herbivore population in check. But some also fear the lions, and killed several in retaliation for attacks on livestock.[74]

In July 2012, a lion dragged a man from the veranda of his house and killed him about 50–60 km (31–37 miles) from Gir Forest National Park. This was the second attack by a lion in this area, six months after a 25-year-old man was attacked and killed in Dhodadar.[75]

Conservation

[edit]Panthera leo persica was included on CITES Appendix I, and is fully protected in India,[38] where it is considered endangered.[76]

Reintroduction

[edit]

India

[edit]In the 1950s, biologists advised the Indian government to re-establish at least one wild population in the Asiatic lion's former range to ensure the population's reproductive health and to prevent it from being affected by an outbreak of an epidemic. In 1956, the Indian Board for Wildlife accepted a proposal by the Government of Uttar Pradesh to establish a new sanctuary for the envisaged reintroduction, Chandra Prabha Wildlife Sanctuary, covering 96 km2 (37 sq mi) in eastern Uttar Pradesh, where climate, terrain and vegetation is similar to the conditions in the Gir Forest. In 1957, one male and two female wild-caught Asiatic lions were set free in the sanctuary. This population comprised 11 animals in 1965, which all disappeared thereafter.[77]

The Asiatic Lion Reintroduction Project to find an alternative habitat for reintroducing Asiatic lions was pursued in the early 1990s. Biologists from the Wildlife Institute of India assessed several potential translocation sites for their suitability regarding existing prey population and habitat conditions. The Palpur-Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary in northern Madhya Pradesh was ranked as the most promising location, followed by Sita Mata Wildlife Sanctuary and Darrah National Park.[78] Until 2000, 1,100 families from 16 villages had been resettled from the Palpur-Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary, and another 500 families from eight villages were expected to be resettled. With this resettlement scheme the protected area was expanded by 345 km2 (133 sq mi).[77][79]

Gujarat state officials resisted the relocation, since it would make the Gir Sanctuary lose its status as the world's only home of the Asiatic lion. Gujarat raised a number of objections to the proposal, and thus the matter went before the Indian Supreme Court. In April 2013, the Indian Supreme Court ordered the Gujarat state to send some of their Gir lions to Madhya Pradesh to establish a second population there.[80] The court had given wildlife authorities six months to complete the transfer. The number of lions and which ones to be transported will be decided at a later date. As of now, the plan to shift lions to Kuno is in jeopardy, with Madhya Pradesh having apparently given up on acquiring lions from Gujarat.[81][82]

Iran

[edit]In 1977, Iran attempted to restore its lion population by transporting Gir lions to Arzhan National Park, but the project met resistance from the local population, and thus it was not implemented.[49][54] However, this did not stop Iran from seeking to bring back the lion.[83][84] In February 2019, Tehran Zoological Garden obtained a male Asiatic lion from Bristol Zoo in the United Kingdom,[85] followed in June by a female from Dublin Zoo. There are hopes for them to successfully reproduce.[86]

In captivity

[edit]Until the late 1990s, captive Asiatic lions in Indian zoos were haphazardly interbred with African lions confiscated from circuses, leading to genetic pollution in the captive Asiatic lion stock. Once discovered, this led to the complete shutdown of the European and American endangered species breeding programs for Asiatic lions, as its founder animals were captive-bred Asiatic lions originally imported from India and were ascertained to be intraspecific hybrids of African and Asian lions. In North American zoos, several Indian-African lion crosses were inadvertently bred, and researchers noted that "the fecundity, reproductive success, and spermatozoal development improved dramatically."[87][88]

DNA fingerprinting studies of Asiatic lions have helped in identifying individuals with high genetic variability, which can be used for conservation breeding programs.[89]

In 2006, the Central Zoo Authority of India stopped breeding Indian-African cross lions stating that "hybrid lions have no conservation value and it is not worth to spend resources on them".[87][90] Now only pure native Asiatic lions are bred in India.

In 1972 the Sakkarbaug Zoo sold a pair of young pure-stock lions to the Fauna Preservation Society; which decided they would be accommodated at the Jersey Wildlife Trust where it was hoped to begin a captive breeding programme.[91]

The Asiatic lion International Studbook was initiated in 1977, followed in 1983 by the North American Species Survival Plan (SSP).[92] The North American population of captive Asiatic lions was composed of descendants of five founder lions, three of which were pure Asian and two were African or African-Asian hybrids. The lions kept in the framework of the SSP consisted of animals with high inbreeding coefficients.[27]

In the early 1990s, three European zoos imported pure Asiatic lions from India: London Zoo obtained two pairs; the Zürich Zoologischer Garten one pair; and the Korkeasaari Zoo in Helsinki one male and two females. In 1994, the European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) for Asiatic lions was initiated. The European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) published the first European Studbook in 1999. By 2005, there were 80 Asiatic lions kept in the EEP – the only captive population outside of India.[92] As of 2009, more than 100 Asiatic lions were kept within the EEP. The SSP had not resumed; pure-bred Asiatic lions are needed to form a new founder population for breeding in American zoos.[93]

In culture

[edit]South and East Asia

[edit]Neolithic cave paintings of lions were found in Bhimbetka rock shelters in central India, which are at least 30,000 years old.[94]

The Sanskrit word for 'lion' is 'सिंह' siṃhaḥ, which is also a name of Shiva and signifies the Leo of the Zodiac.[95] The Sanskrit name of Sri Lanka is Sinhala meaning 'Abode of Lions'.[96] Singapore derives its name from the Malay words singa 'lion' and pura 'city', which in turn is from the Sanskrit 'सिंह' siṃhaḥ and पुर pur, latter also meaning 'fortified town'.[95][97]

In Hindu mythology, the half man half lion avatar Narasimha is the fourth incarnation of Vishnu.[98] Simhamukha is a lion-faced protector and dakini in Tibetan Buddhism.[99]

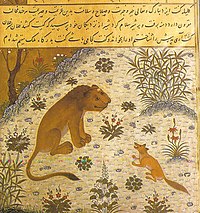

In the 18th book of the Mahabharata, Bharata deprives lions of their prowess.[100] The lion plays a prominent role in The Fables of Pilpay that were translated into Persian, Greek and Hebrew languages between the 8th and 12th centuries.[101] The lion is the symbol of Mahavira, the 24th and last Tirthankara in Jainism.[102][103]

- The lion is the third animal of the Burmese zodiac and the sixth animal of the Sinhalese zodiac.[104]

- The earliest known Chinese stone sculptures of lions date to the Han dynasty at the turn of the first millennium.[105]

- The lion dance is a traditional dance in Chinese culture that is strongly associated with Buddhism and known since at least the Han dynasty.[106]

- Cambodia has a native martial art called Bokator (Khmer: ល្បុក្កតោ, pounding a lion).[107]

West Asia and Europe

[edit]Lions are depicted on vases dating to about 2600 BCE that were excavated near Lake Urmia in Iran.[108] The lion was an important symbol in Ancient Iraq and is depicted in a stone relief at Nineveh in the Mesopotamian Plain.[109][110]

- The lion makes repeated appearances in the Bible, most notably as having fought Samson in the Book of Judges.[citation needed]

- Having occurred in the Arab world, particularly the Arabian Peninsula,[33] the Asiatic lion has significance in Arab and Islamic culture. For example, Surah al-Muddaththir of the Quran criticizes people who were averse to the Islamic Prophet Muhammad's teachings, such as that the rich have an obligation to donate wealth to the poor, comparing their attitude to itself, with the response of prey to a qaswarah (Arabic: قَسْوَرَة, meaning "lion", "beast of prey", or "hunter").[111] Other Arabic words for 'lion' include asad (Arabic: أَسَد) and sabaʿ (Arabic: سَبَع),[112] and they can be used as names of places, or titles of people. An Arabic toponym for the Levantine City of Beersheba (Arabic: بِئر ٱلسَّبَع) can mean "Spring of the Lion."[113] Ali ibn Abi Talib and Hamzah ibn Abdul-Muttalib, who were loyal kinsmen of Muhammad, were given titles like Asad Allah (Arabic: أَسَد ٱلله, lit. 'Lion of God').[114]

- The lion of Babylon is a statue at the Ishtar Gate in Babylon[49] The lion has an important association with the figure Gilgamesh, as demonstrated in his epic.[115] The Iraqi national football team is nicknamed "Lions of Mesopotamia."[116]

- The symbol of the lion is closely tied to the Persian people. Achaemenid kings were known to carry the symbol of the lion on their thrones and garments. The name 'Shir' (also pronounced 'Sher') (Persian: شیر) is a part of the names of many places in Iran and Central Asia, like those of city of Shiraz and the Sherabad River, and had been adopted into other languages, like Hindi.[3][33][49] The Shir-va-Khorshid (Persian: شیر و خورشید, "Lion and Sun") is one of the most prominent symbols of Iran, dating back to the Safavid dynasty, and was used on the flag of Iran until 1979.[117]

- The lion was an objective of hunting in the Caucasus, by both locals and foreigners. The locals were called 'Shirvanshakhs'.[33]

- The Nemean lion of pre-literate Greek myth is associated with the Labours of Hercules.[118]

- A Bronze Age statue of a lion from either Southern Italy or southern Spain from around 1000–1200 years BCE, the "Mari-Cha Lion", was exhibited at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.[119]

See also

[edit]- Lion populations: Cape lion · Lions in Europe ·

References

[edit]- ^ a b Breitenmoser, U.; Mallon, D.P.; Ahmad Khan, J.; Driscoll, C. (2023). "Panthera leo (Asiatic subpopulation) (amended version of assessment)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2023: e.T247279613A247284471. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T247279613A247284471.en. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Meyer, J. N. (1826). Dissertatio inauguralis anatomico-medica de genere felium (Doctoral thesis). Vienna: University of Vienna.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera leo". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis Ltd. pp. 212–222.

- ^ Bennett, E. T. (1829). The Tower Menagerie, Comprising the Natural History of the Animals Contained in That Establishment; With Anecdotes of Their Characters and History. London: Robert Jennings.

- ^ Smee, W. (1833). "Felis leo, Linn., Var. goojratensis". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Part I (December 1833): 140.

- ^ Jardine, W. (1834). "The Lion". Natural History of the Felinae. Series: Naturalist's library. London: H. G. Bohn. p. 87−123.

- ^ Blainville, H. M. D. (1843). "Felis. Plate VI.". Ostéographie, ou Description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossiles pour servir de base à la zoologie et à la géologie. Paris: J.B. Ballière et fils. Archived from the original on 2014-12-03. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 71–73. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-17. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- ^ Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A. C.; Driscoll, C. A.; Macdonald, D. W. (2009). "Divided infraorbital foramen in the lion (Panthera leo): its implications for colonisation history, population bottlenecks, and conservation of the Asian lion (P. l. persica)". Contributions to Zoology. 78 (2): 77–83. doi:10.1163/18759866-07802004. Archived from the original on 2020-06-02. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ a b Singh, H. S. (2017). "Dispersion of the Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica and its survival in human-dominated landscape outside the Gir forest, Gujarat, India". Current Science. 112 (5): 933–940. doi:10.18520/cs/v112/i05/933-940.

- ^ Singh, A. P. & Nala, R. R. (2018). "Estimation of the Status of Asiatic Lion (Panthera leo persica) Population in Gir Lion Landscape, Gujarat, India". Indian Forester. 144 (10): 887–892.

- ^ Schnitzler, A. & Hermann, L. (2019). "Chronological distribution of the tiger Panthera tigris and the Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica in their common range in Asia". Mammal Review. 49 (4): 340–353. doi:10.1111/mam.12166. S2CID 202040786.

- ^ Finch, K.; Williams, L. & Holmes, L. (2020). "Using longitudinal data to evaluate the behavioural impact of a switch to carcass feeding on an Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica)". Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research. 8 (4): 283–287. doi:10.19227/jzar.v8i4.475.

- ^ Chaudhary, R.; Zehra, N.; Musavi, A. & Khan, J.A. (2020). "Spatio-temporal partitioning and coexistence between leopard (Panthera pardus fusca) and Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) in Gir protected area, Gujarat, India". PLOS One. 15 (3): e0229045. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1529045C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229045. PMC 7065753. PMID 32160193.

- ^ Sood, P. (2020). "Biogeographical distribution of Asiatic Lion (Panthera leo persica), Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) in ancient, medieval and modern Rajasthan: Study of plans to relocate them in Rajasthan". Indian Journal of Environmental Sciences. 24 (1): 35–41.

- ^ Broggini, C.; Cavallini, M.; Vanetti, I.; Abell, J.; Binelli, G.; Lombardo, G. (2024). "From Caves to the Savannah, the Mitogenome History of Modern Lions (Panthera leo) and Their Ancestors". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 25 (10). 5193. doi:10.3390/ijms25105193. PMC 11121052. PMID 38791233.

- ^ Manuel, M. d.; Ross, B.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M.-H. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H.; O'Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T. & Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (20): 10927–10934. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11710927D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- ^ a b Pokines, James T.; Lister, Adrian M.; Ames, Christopher J. H.; Nowell, April; Cordova, Carlos E. (March 2019). "Faunal remains from recent excavations at Shishan Marsh 1 (SM1), a Late Lower Paleolithic open-air site in the Azraq Basin, Jordan". Quaternary Research. 91 (2): 768–791. doi:10.1017/qua.2018.113. ISSN 0033-5894.

- ^ Mashkour, M.; Monchot, H.; Trinkaus, E.; Reyss, J.-L.; Biglari, F.; Bailon, S.; Heydari, S.; Abdi, K. (November 2009). "Carnivores and their prey in the Wezmeh Cave (Kermanshah, Iran): a Late Pleistocene refuge in the Zagros". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 19 (6): 678–694. doi:10.1002/oa.997. ISSN 1047-482X.

- ^ Dutta, A. K. (1976). "Occurrence of fossil lion and spotted hyena from Pleistocene deposits of Susunia, Bankura District, West Bengal". Journal of the Geological Society of India. 17 (3): 386–391. Archived from the original on 2022-10-06. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- ^ Manamendra-Arachchi, K.; Pethiyagoda, R.; Dissanayake, R. & Meegaskumbura, M. (2005). "A second extinct big cat from the late Quaternary of Sri Lanka". The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology (Supplement 12): 423–434. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I. & Cooper, A. (2006). "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 273 (1598): 2119–2125. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3555. PMC 1635511. PMID 16901830.

- ^ Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H. & Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The evolutionary dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo revealed by host and viral population genomics". PLOS Genetics. 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMC 2572142. PMID 18989457.

- ^ Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J.; Udo De Haes, H. A.; Leirs, H.; Van Haeringen, W. A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Tumenta, P. N. & De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 38 (7): 1356–1367. Bibcode:2011JBiog..38.1356B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. S2CID 82728679. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2017-01-17.

- ^ Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P.; White, P.A.; Driscoll, C.A.; Tende, T.; Ottosson, U.; Saidu, Y.; Vrieling, K. & De Iongh, H. H. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports. 6: 30807. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630807B. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMC 4973251. PMID 27488946.

- ^ O’Brien, S. J.; Martenson, J. S.; Packer, C.; Herbst, L.; de Vos, V.; Joslin, P.; Ott-Joslin, J.; Wildt, D. E. & Bush, M. (1987). "Biochemical genetic variation in geographic isolates of African and Asiatic lions" (PDF). National Geographic Research. 3 (1): 114–124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-02.

- ^ a b O’Brien, S. J.; Joslin, P.; Smith, G. L. III; Wolfe, R.; Schaffer, N.; Heath, E.; Ott-Joslin, J.; Rawal, P. P.; Bhattacharjee, K. K. & Martenson, J. S. (1987). "Evidence for African origins of founders of the Asiatic lion Species Survival Plan" (PDF). Zoo Biology. 6 (2): 99–116. doi:10.1002/zoo.1430060202. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-25. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ Sterndale, R. A. (1884). "No. 200 Felis leo". Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co. pp. 159–161.

- ^ Smuts, G.L.; Robinson, G.A. & Whyte, I.J. (1980). "Comparative growth of wild male and female lions (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology. 190 (3): 365–373. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1980.tb01433.x.

- ^ a b Chellam, R. & Johnsingh, A. J. T. (1993). "Management of Asiatic lions in the Gir Forest, India". In Dunstone, N. & Gorman, M. L. (eds.). Mammals as predators: the proceedings of a symposium held by the Zoological Society of London and the Mammal Society, London. Volume 65 of Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. London: Zoological Society of London. pp. 409–423.

- ^ Jhala, Yadvendradev V.; Banerjee, Kausik; Chakrabarti, Stotra; Basu, Parabita; Singh, Kartikeya; Dave, Chittaranjan; Gogoi, Keshab (2019). "Asiatic Lion: Ecology, Economics, and Politics of Conservation". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00312. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species (762): 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198968757. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Lion". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I. & Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation". Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507–514. Bibcode:2006ConG....7..507B. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. S2CID 24190889.

- ^ Sinha, S. P. (1987). Ecology of wildlife with special reference to the lion (Panthera leo persica) in Gir Wildlife Sanctuary, Saurashtra, Gujurat (PhD thesis). Rajkot: Saurashtra University. ISBN 3844305459.

- ^ Brakefield, T. (1993). "Lion: physical characteristics". Big Cats. St. Paul: Voyageur Press. p. 67. ISBN 9781610603546.

- ^ a b c d e Kinnear, N. B. (1920). "The past and present distribution of the lion in south eastern Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 27: 34–39.

- ^ a b Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). "Asiatic lion" (PDF). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 37–41. ISBN 978-2-8317-0045-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-05-29. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- ^ a b c d e Singh, H. S. & Gibson, L. (2011). "A conservation success story in the otherwise dire megafauna extinction crisis: The Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) of Gir forest". Biological Conservation. 144 (5): 1753–1757. Bibcode:2011BCons.144.1753S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.707.1382. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.02.009.

- ^ a b Varma, K. (2009). "The Asiatic Lion and the Maldharis of Gir Forest" (PDF). The Journal of Environment & Development. 18 (2): 154–176. doi:10.1177/1070496508329352. S2CID 155086420. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ Venkataraman, M. (2016). "Wildlife and human impacts in the Gir landscape". In Agrawal, P. K.; Verghese, A.; Krishna, S. R.; Subaharan, K. (eds.). Human Animal Conflict in Agro-Pastoral Context: Issues & Policies. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research. p. 32−40.

- ^ Singh, A. P. (2017). "The Asiatic Lion (Panthera leo persica): 50 years journey for conservation of an Endangered carnivore and its habitat in Gir Protected Area, Gujarat, India". Indian Forester. 143 (10): 993–1003. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ^ Kaushik, H. (2017). "Lion population roars to 650 in Gujarat forests". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Kagathara, T. & Bharucha, E. (2020). "Building walls around open wells prevent Asiatic Lion Panthera leo persica (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) mortality in the Gir Lion Landscape, Gujarat, India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 12 (3): 15301–15310. doi:10.11609/jott.5025.12.3.15301-15310.

- ^ Sushmita Pathak (19 May 2023). "Why are India's lions increasingly swapping the jungle for the beach?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ a b Marciszak, A.; Ivanoff, D. V.; Semenov, Y. A.; Talamo, S.; Ridush, B.; Stupak, A.; Yanish, Y.; Kovalchuk, O. (2022). "The Quaternary lions of Ukraine and a trend of decreasing size in Panthera spelaea". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 30 (1): 109–135. doi:10.1007/s10914-022-09635-3. hdl:11585/903022.

- ^ Schnitzler, A.E. (2011). "Past and present distribution of the North African-Asian lion subgroup: a review". Mammal Review. 41 (3): 220–243. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2010.00181.x.

- ^ Sevruguin, A. (1880). "Men with live lion". National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, The Netherlands; Stephen Arpee Collection. Archived from the original on 2018-03-26. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ a b c d Humphreys, P.; Kahrom, E. (1999). "Lion". Lion and Gazelle: The Mammals and Birds of Iran. Avon: Images Publishing. pp. 77−80. ISBN 978-0951397763.

- ^ Nader, I. A. (1989). "Rare and endangered mammals of Saudi Arabia" (PDF). In Abu-Zinada, A. H.; Goriup, P. D.; Nader, L. A (eds.). Wildlife conservation and development in Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development Publishing. pp. 220–228. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ Üstay, A. H. (1990). Hunting in Turkey. Istanbul: BBA.

- ^ Hatt, R. T. (1959). The mammals of Iraq. Ann Arbor: Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan.

- ^ Khosravifard, S. & Niamir, A. (2016). "The lair of the lion in Iran". Cat News (Special Issue 10): 14–17. Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ^ a b Firouz, E. (2005). "Lion". The complete fauna of Iran. London, New York: I. B. Tauris. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-85043-946-2.

- ^ Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1961). Simba: The Life of the Lion. Cape Town: Howard Timmins.

- ^ a b Mitra, S. (2005). Gir Forest and the saga of the Asiatic lion. New Delhi: Indus. ISBN 978-8173871832.

- ^ a b Blanford, W. T. (1889). "Felis leo. The Lion". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 56–58.

- ^ Sharma, B. K.; Kulshreshtha, S.; Sharma, S.; Singh, S.; Jain, A.; Kulshreshtha, M. (2013). "In situ and ex situ conservation: Protected Area Network and zoos in Rajasthan". In Sharma, B. K.; Kulshreshtha, S.; Rahmani, A. R. (eds.). Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India: Conservation and Management of Vertebrates. Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783319013459.

- ^ Joslin, P. (1973). The Asiatic lion: a study of ecology and behaviour. University of Edinburgh, UK: Department of Forestry and Natural Resources.

- ^ a b Meena V. (2008). Reproductive strategy and behaviour of male Asiatic Lions. Dehra Dun: Wildlife Institute of India.

- ^ a b c Chellam, R. (1993). Ecology of the Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica). Saurashtra University, Rajkot, India: Wildlife Institute of India.

- ^ Chellam, R. (1997). "Asia's Envy, India's Pride". Srishti: 66–72.

- ^ Jhala, Y. V.; Mukherjee, S.; Shah, N.; Chauhan, K. S.; Dave, C. V.; Meena, V. & Banerjee, K. (2009). "Home range and habitat preference of female lions (Panthera leo persica) in Gir forests, India". Biodiversity and Conservation. 18 (13): 3383–3394. Bibcode:2009BiCon..18.3383J. doi:10.1007/s10531-009-9648-9. S2CID 21167393.

- ^ a b Johnsingh, A.J.T. & Chellam, R. (1991). "Asiatic lions". In Seidensticker, J.; Lumpkin, S. & Knight, F. (eds.). Great Cats. London: Merehurst. pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c Chakrabarti, S. & Jhala, Y. V. (2017). "Selfish partners: resource partitioning in male coalitions of Asiatic lions". Behavioral Ecology. 28 (6): 1532–1539. doi:10.1093/beheco/arx118. PMC 5873260. PMID 29622932.

- ^ Chaudhary, R.; Zehra, N.; Musavi, A. & Khan, J.A. (2020). "Spatio-temporal partitioning and coexistence between leopard (Panthera pardus fusca) and Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) in Gir protected area, Gujarat, India". PLOS One. 15 (3): p.e0229045. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1529045C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229045. PMC 7065753. PMID 32160193.

- ^ Hayward, M. W. & Kerley, G. I. H. (2005). "Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo)" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 267 (3): 309–322. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.611.8271. doi:10.1017/S0952836905007508. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-05. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ Jhala, Y. V.; Banerjee, K.; Basu, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Gayen, S.; Gogoi, K. & Basu, A. (2016). Ecology of Asiatic Lions in Gir, P. A., and Adjoining Human-Dominated Landscape of Saurashtra, Gujarat (Report). Dehradun, India: Wildlife Institute of India.

- ^ Annual Report (Report). Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. 1972. p. 42.

- ^ Chellam, R. (1987). "The Gir Lions". Vivekananda Kendra Patrika: 153–157.

- ^ Chakrabarti, S. & Jhala, Y. V. (2019). "Battle of the sexes: a multi-male mating strategy helps lionesses win the gender war of fitness". Behavioral Ecology. 30 (4): 1050–1061. doi:10.1093/beheco/arz048.

- ^ Bobins, A. (2018). "Did The Failure To Set Up A 'Second Home' For in Madhya Pradesh Cause Lion Deaths in Gir?". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ^ "Asiatic lions in Gujarat's Gir forest dying of Canine Distemper Virus: ICMR". The Hindustan Times. New Delhi. 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ^ Meena, V. (2016). "Wildlife and human impacts in the Gir landscape". In Agrawal, P.K.; Verghese, A.; Radhakrishna, S.; Subaharan, K. (eds.). Human Animal Conflict in Agro-Pastoral Context: Issues & Policies. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

- ^ Anonymous (2012). "Man-eater lion kills 50-year-old in Amreli, preys on him". Daily News and Analysis. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Zoological Survey of India (1994). Red Data Book on Indian Animals. Part. 1: Vertebrata (Mammalia, Aves, Reptilia and Amphibia), The (PDF). Calcutta: White Lotus Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-06. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ^ a b Johnsingh, A.J.T. (2006). "Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary ready to play second home to Asiatic lions?". Field Days: A Naturalist's Journey Through South and Southeast Asia. Hyderabad: Universities Press. pp. 126–138. ISBN 978-8173715525.

- ^ Walker, S. (1994). Executive summary of the Asiatic lion PHVA. First draft report. Zoo's Print: 2–22.

- ^ Hugo, K. (2016). "Asia's Lions Live in One Last Place on Earth—And They're Thriving". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Anand, U. (2013). Supreme Court gives Madhya Pradesh lions' share from Gujarat's Gir Archived 2013-05-20 at the Wayback Machine. The Indian Express Ltd., 17 April 2013.

- ^ Sharma, R. (2017). "Tired of Gujarat reluctance on Gir lions, MP to release tigers in Kuno". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2018-01-28. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ "Stalemate on translocation of Gir lions Kuno Palpur in Madhya Pradesh to be used as tiger habitat now". Hindustan Times. 2017. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Dey, A. (2009). "Rajasthan to be home for cheetahs". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2012-10-24. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ Khosravifard, S. (2010). "Russia, Iran exchange tigers for leopards but some experts express doubts". Payvand News. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ Amlashi, H. (2019). "Return To Motherland: Asiatic lion returns to Iran after 80 years". Tehran Times. Archived from the original on 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- ^ "From Dublin to Tehran: Persian Lioness Joins Male Companion". Iran Front Page. 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- ^ a b Tudge, C. (2011). Engineer in the Garden. Random House. p. 42. ISBN 9781446466988.

- ^ Avise, J. C.; Hamrick, J. L. (1996). Conservation Genetics: Case Histories from Nature. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 67. ISBN 9780412055812.

- ^ Shankaranarayanan, P.; Banerjee, M.; Kacker, R. K.; Aggarwal, R. K.; Singh, L. (1997). "Genetic variation in Asiatic lions and Indian tigers" (PDF). Electrophoresis. 18 (9): 1693–1700. doi:10.1002/elps.1150180938. PMID 9378147. S2CID 41046139. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-23.

- ^ "Hybrid lions at Chhatbir Zoo in danger". The Times of India. 18 September 2006. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ Annual Report 1972: Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust; pp 39-42 Archived 2023-09-18 at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ a b Zingg, R. (2007). "Asiatic Lion Studbooks: a short history" (PDF). Zoos' Print Journal. XXII (6): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-28.

- ^ "The Asiatic lion captive breeding programme". asiatic-lion.org. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06.

- ^ Badam, G. L. & Sathe, V. G. (1991). "Animal depictions in rock art and palaeoecology—a case study at Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh, India". In Pager, S. A.; Swatrz Jr., B. K. & Willcox, A. R. (eds.). Rock Art—The Way Ahead: South African Rock Art Research Association First International Conference Proceedings. Natal: Southern African Rock Art Research Association. pp. 196–208.

- ^ a b Apte, V. S. (1957–1959). "सिंहः siṃhaḥ". Revised and enlarged edition of Prin. V. S. Apte's The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan. p. 1679. Archived from the original on 2021-09-12. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ "Chinese account of Ceylon". The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australasia. 20 (May): 30. 1836.

- ^ Apte, V. S. (1957–1959). "पुर् pur". Revised and enlarged edition of Prin. V. S. Apte's The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan. p. 1031. Archived from the original on 2021-09-13. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- ^ Williams, G. M. (2008). "Narasimha". Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ Loseries, A. (2013). "Simhamukha: The Lion-faced Durgā of the Tibetan Tantrik Pantheon". In Loseries, A. (ed.). Tantrik Literature and Culture : Hermeneutics and Expositions. Delhi: Buddhist World Press. pp. 155–164. ISBN 978-93-80852-20-1.

- ^ Ganguli, K. M. (1883–1896). "Book 7: Drona Parva. Section LXVIII". The Mahabharata. John Bruno Hare. Archived from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ Eastwick, E. B (transl.) (1854). The Anvari Suhaili; or the Lights of Canopus Being the Persian version of the Fables of Pilpay; or the Book Kalílah and Damnah rendered into Persian by Husain Vá'iz U'L-Káshifí. Hertford: Stephen Austin, Bookseller to the East-India College.

- ^ Ansari, U. (2017). "Mahavira". The Mega Yearbook 2018 – Current Affairs & General Knowledge for Competitive Exams with 52 Monthly ebook Updates & eTests (3 ed.). Disha Publications. p. 102. ISBN 978-9387421226. Archived from the original on 2024-01-22. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Reddy (2006). Indian Hist (Opt). Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 155. ISBN 978-0070635777. Archived from the original on 2024-01-22. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ Upham, E. (1829). The History and Doctrine of Budhism: Popularly Illustrated: with Notices of the Kappooism, Or Demon Worship, and of the Bali, Or Planetary Incantations, of Ceylon. London: R. Ackermann.

- ^ Till, B. (1980). "Some Observations on Stone Winged Chimeras at Ancient Chinese Tomb Sites". Artibus Asiae. 42 (4): 261–281. doi:10.2307/3250032. JSTOR 3250032.

- ^ Yap, J. (2017). "History and Origins". The Art of Lion Dance. Kuala Lumpur: Joey Yap Research Group. pp. 16–33. ISBN 9789671303870. Archived from the original on 2024-01-22. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Ray, N.; Robinson, D.; Bloom, G. (2010). Cambodia. Lonely Planet. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-74179-457-1.

- ^ Gesché-Koning, N. & Van Deuren, G. (1993). Iran. Bruxelles, Belgium: Musées Royaux D'Art et D'Histoire.

- ^ Scarre, C. (1999). The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500050965.

- ^ Ashrafian, H. (2011). "An extinct Mesopotamian lion subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (2): 47–49.

- ^ Quran 74:41–51

- ^ Pease, A. E. (1913). The Book of the Lion. London: John Murray.

- ^ Qumsiyeh, Mazin B. (1996). Mammals of the Holy Land. Texas Tech University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 0-8967-2364-X.

- ^ Muhammad ibn Saad (2013). The Companions of Badr. Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabair. Vol. 3. Translated by Bewley, A. London: Ta-Ha Publishers.

- ^ Dalley, S., ed. (2000). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953836-2.

- ^ "Iraq secure much-needed win over rivals Iran in friendly" (PDF). Iraqi-Football.com. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Shahbazi, S. A. (2001). "Flags (of Persia)". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 10. Archived from the original on 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ^ Wagner, R. A. (ed.). "Index nominum et rerum memorabilium". Mythographi Graeci. Vol. I. Рипол Классик. ISBN 9785874554637. Archived from the original on 2024-01-22. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ Abu Dhabi Department of Culture & Tourism (2017). Annual Report 2017 (PDF) (Report). Vol. 1: Culture. Abu Dhabi. p. 52. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

Further reading

[edit]- Abbott, J. (1856). A Narrative of a journey from Heraut to Khiva, Moscow and St. Petersburgh. Vol. 1. Khiva: James Madden. p. 26. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- Kaushik, H. (2005). "Wire fences death traps for big cats". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2012-09-22.

- Nair, S. M. (1999). Endangered Animals of India and their conservation. Translated by O. Henry Francis (English ed.). National Book Trust.

- Walker, S. (1994). "Executive summary of the Asiatic lion PHVA". Zoo's Print: 2–22. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25.

- Schnitzler, A.; Hermann, L. (2019). "Chronological distribution of the tiger Panthera tigris and the Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica in their common range in Asia". Mammal Review. 49 (4): 340–353. doi:10.1111/mam.12166. S2CID 202040786.

External links

[edit]- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Asiatic lion

- The Telegraph, August 2018: Pride of India

- Asiatic Lion Information Centre at the Wayback Machine (archived August 25, 2010)

- Asiatic Lion Protection Society (ALPS), Gujarat, India

- ARKive.org: Lion (Panthera leo)

- Animal Diversity Web: Panthera leo

- Asiatic lions in online video (3 videos)

- Asiatic Lions Images

- AAj Tak Video News Report in Hindi: Gir lions in palpur kuno century report rajesh badal.mp4 on YouTube by Rajesh Badal (2011)

- DB Video Special Report on Asiatic lion in Gujarati: What Is the connection Between Gir lions and Africans lions

- Skin of a Persian lioness, belonging to an Vulnerable subspecies of lions, brought to Dublin by King Edward VII in 1902 (during the reign of Shah Mozaffar ad-Din in Persia, and kept in the Natural History Museum (Ireland)).

- Lion of Basrah

- A lion in Iraq

- Stuffed animals including Pakistan's last wild lion at Bahawalpur Zoo

- Ancient Arabian account of Muhammad's descendant Musa al-Kadhim encountering a lion outside Medina in the mountainous region of the Hejaz

- Description of the Arabian lion and art

- 4 انواع الأسود في العالم الأسد العربي الجزء (in Arabic)

- الاسد العربي المنقرض عند العرب lion Arabian Extinct (in Arabic)

- Asiatic lioness on a tree