National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom, comprising the NHS in England, NHS Scotland and NHS Wales. Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland was created separately and is often locally referred to as "the NHS".[2] The original three systems were established in 1948 (NHS Wales/GIG Cymru was founded in 1969) as part of major social reforms following the Second World War. The founding principles were that services should be comprehensive, universal and free at the point of delivery—a health service based on clinical need, not ability to pay.[3] Each service provides a comprehensive range of health services, provided without charge for residents of the United Kingdom apart from dental treatment and optical care.[4] In England, NHS patients have to pay prescription charges; some, such as those aged over 60, or those on certain state benefits, are exempt.[5]

Taken together, the four services in 2015–16 employed around 1.6 million people with a combined budget of £136.7 billion.[6] In 2024, the total health sector workforce across the United Kingdom was 1,499,368 making it the seventh largest employer and second largest non-military public organisation in the world.[7][8][9][10]

When purchasing consumables such as medications, the four healthcare services have significant market power that influences the global price, typically keeping prices lower.[11] A small number of products are procured jointly through contracts shared between services.[12] Several other countries directly rely on Britain's assessments for their own decisions on state-financed drug reimbursements.[13]

History

[edit]

Calls for a "unified medical service" can be dated back to the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Law in 1909.[15]

Somerville Hastings, President of the Socialist Medical Association, successfully proposed a resolution at the 1934 Labour Party Conference that the party should be committed to the establishment of a State Health Service.[16]

Following the 1942 Beveridge Report's recommendation to create "comprehensive health and rehabilitation services for prevention and cure of disease", cross-party consensus emerged on introducing a National Health Service of some description.[17] Conservative MP and Health Minister, Henry Willink later advanced this notion of a National Health Service in 1944 with his consultative White Paper "A National Health Service" which was circulated in full and short versions to colleagues, as well as in newsreel.[18]

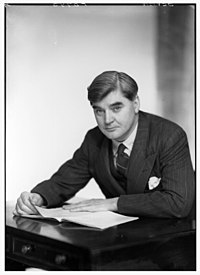

When Clement Attlee's Labour Party won the 1945 election he appointed Aneurin Bevan as Health Minister. Bevan then embarked upon what the official historian of the NHS, Charles Webster, called an "audacious campaign" to take charge of the form the NHS finally took.[19] Bevan's National Health Service was proposed in Westminster legislation for England and Wales from 1946 and Scotland from 1947, and the Northern Ireland Parliament's Public Health Services Act 1947.[20] NHS Wales was split from NHS (England) in 1969 when control was passed to the Secretary of State for Wales.[21] According to one history of the NHS, "In some respects the war had made things easier. In anticipation of massive air raid casualties, the Emergency Medical Service had brought the country's municipal and voluntary hospitals into one umbrella organisation, showing that a national hospital service was possible."[22] Webster wrote in 2002 that "the Luftwaffe achieved in months what had defeated politicians and planners for at least two decades."[23]

The NHS was born out of the ideal that healthcare should be available to all, regardless of wealth. Although being freely accessible regardless of wealth maintained Henry Willink's principle of free healthcare for all, Conservative MPs were in favour of maintaining local administration of the NHS through existing arrangements with local authorities fearing that an NHS which owned hospitals on a national scale would lose the personal relationship between doctor and patient.[24]

Conservative MPs voted in favour of their amendment to Bevan's Bill to maintain local control and ownership of hospitals and against Bevan's plan for national ownership of all hospitals. The Labour government defeated Conservative amendments and went ahead with the NHS as it remains today; a single large national organisation (with devolved equivalents) which forced the transfer of ownership of hospitals from local authorities and charities to the new NHS. Bevan's principle of ownership with no private sector involvement has since been diluted, with later Labour governments implementing large scale financing arrangements with private builders in private finance initiatives and joint ventures.[25]

At its launch by Bevan on 5 July 1948 it had at its heart three core principles: That it meet the needs of everyone, that it be free at the point of delivery, and that it be based on clinical need, not ability to pay.[26]

Three years after the founding of the NHS, Bevan resigned from the Labour government in opposition to the introduction of charges for the provision of dentures, dentists,[27] and glasses; resigning in support was fellow minister and future Prime Minister Harold Wilson.[28] The following year, Winston Churchill's Conservative government introduced prescription fees. However, Wilson's government abolished them in 1965; they were later re-introduced but with exemptions for those on low income.[29] These charges were the first of many controversies over changes to the NHS throughout its history.[30]

From its earliest days, the cultural history of the NHS has shown its place in British society reflected and debated in film, TV, cartoons and literature. The NHS had a prominent slot during the 2012 London Summer Olympics opening ceremony directed by Danny Boyle, being described as "the institution which more than any other unites our nation".[31]

Eligibility for treatment

[edit]Some health services are free to everyone, including accident and emergency room treatment, registering with a GP and attending GP appointments, treatment for some infectious diseases, compulsory psychiatric treatment, and some family planning services.[32][33]

Everyone living in the UK can use the NHS without being asked to pay the full cost of the service, though NHS dentistry and optometry have standard charges in each of the four national health services in the UK.[34] Most patients in England have to pay charges for prescriptions though some patients are exempted.[5]

People who are not ordinarily resident (including British citizens who may have paid National Insurance contributions in the past) may have to pay for services, with some exceptions such as refugees.[4][35] Patients who do not qualify for free treatment are asked to pay in advance or to sign a written promise to pay for treatment.[32]

There are some other categories of people who are exempt from the residence requirements such as specific government workers, those in the armed forces stationed overseas, and those working outside the UK as a missionary for an organisation with its principal place of business in the UK.[36]

Citizens of the EU or European Economic Area (EEA) nations holding a valid European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) and people from certain other countries with which the UK has reciprocal arrangements concerning health care can get NHS emergency treatment without charge.[32][37] People from the EU without an EHIC, Provisional Replacement Certificate (PRC)[38] or S1 or S2 visa may have to pay.[39]

People applying for a visa or immigration application for more than six months have to pay an immigration health surcharge when applying for their visa and can then get treatment on the same basis as a resident. There are some people who do not have to pay, including health and care workers and their dependents, dependents of some members of the armed forces, and victims of slavery or domestic violence.[40] In 2024, the charges were £776 per year for students, their dependents, those on Youth Mobility Schemes, and those under aged 18, and £1035 for all other applicants who are not covered by exemptions.[41]

Funding

[edit]The NHS is funded by general taxation and National Insurance contributions, plus around 1% of funding from patient charges for some services.[42]

In 2022/3, £181.7 billion was spent by the Department of Health and Social Care on services in England. More than 94% of spend was on salaries and medicines.[42]

In 2024/5, the NHS in Wales budgeted £11.74 billion for health and social care, which was 49% of its budget.[43]

£19.5 billion was budgeted for health and social care in Scotland for 2024/5.[44]

£7.3 billion was budgeted for health in Northern Ireland in 2024/5.[45]

Staffing

[edit]The NHS is the largest employer in Europe, with one in every 25 adults in England working for the NHS.[46] As of February 2023, NHS England employed 1.4 million staff.[47] Nursing staff accounted for the largest cohort at more than 330,000 employees, followed by clinical support staff at 290,000, scientific and technical staff at 163,000 and doctors at 133,000.[48]

Issues

[edit]Funding and costs

[edit]The funding of the NHS is usually an election issue, and fell under scrutiny during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In July 2022, The Telegraph reported that think tank Civitas found that health spending was costing about £10,000 per household in the UK. They said that this was the third highest share of GDP of any nation in Europe and claimed that the UK "has one of the most costly health systems – and some of the worst outcomes". The findings were made before the government increased health spending significantly, with a 1.25% increase in National Insurance, in April 2022. Civitas said that "runaway" health spending in the UK had increased by more than any country despite the drop in national income due to the COVID pandemic.[49]

The Labour Government elected in 2024 stated that their policy was that the "NHS is broken".[50] They announced an immediate stocktake of current pressures led by Labour peer Lord Ara Darzi.[51] This was to be followed by development of a new "10 year plan" for the NHS to replace the NHS Long Term Plan published in 2019.[52]

The potential rise of the cost of social care has been signaled by research. Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard of the Royal College of GPs said: [when?] "It's a great testament to medical research, and the NHS, that we are living longer – but we need to ensure that our patients are living longer with a good quality of life. For this to happen we need a properly funded, properly staffed health and social care sector with general practice, hospitals and social care all working together – and all communicating well with each other, in the best interests of delivering safe care to all our patients."[53]

Employment and waiting lists

[edit]

In June 2018, the Royal College of Physicians calculated that medical training places need to be increased from 7,500 to 15,000 by 2030 to take account of part-time working among other factors. At that time there were 47,800 consultants working in the UK of which 15,700 were physicians. About 20% of consultants work less than full-time.[55]

On 6 June 2022, The Guardian said that a survey of more than 20,000 frontline staff by the nursing trade union and professional body, the Royal College of Nursing, found that only a quarter of shifts had the planned number of registered nurses on duty.[56]

The NHS will potentially have a shortage of general practitioners. From 2015 to 2022, the number of GPs fell by 1,622 and some of those continuing to work have changed to work part-time. [57]

In 2023, a report revealed that NHS staff had faced over incidents of 20,000 sexual misconduct from patients from 2017 to 2022 across 212 NHS Trusts.[citation needed]

In June 2023, the delayed NHS Long Term Workforce Plan was announced, to train doctors and nurses and create new roles within the health service.[58]

The Welsh and UK governments announced a partnership on 23 September 2024 to reduce NHS waiting lists in England and Wales during the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool. This collaboration aimed to share best practices and tackle common challenges. Previously, Eluned Morgan rejected a Conservative proposal for treating Welsh patients in England. The Welsh Conservatives welcomed the new partnership as overdue, while Plaid Cymru criticized it as insufficient for addressing deeper issues within the Welsh NHS.[59]

Mental health

[edit]One in four patients throughout the UK wait over three months to see an NHS mental health professional, with 6% waiting at least a year.[60] The National Audit Office found mental health provisions for children and young people will not meet growing demand, despite promises of increased funding. Currently one-quarter of young people needing mental health services can get NHS help.The Department of Health and Social Care hopes to raise the ratio to 35%. Efforts to improve mental health provisions could reveal previously unmet demand.[61]

NHS England is expanding mental health services.[62] The mental health charity, Mind, said that the £2.3bn a year was important and that the "longer-term strategy was developed in consultation with people with mental health problems to ensure their views are reflected."[62]

Inclusion

[edit]In 2024, some NHS hospitals required radiographers to ask all male patients aged 12 to 55 if they were pregnant for inclusivity purposes. This received a lot of coverage in the media.[63][64][65][66]

Performance

[edit]Performance of the NHS is generally assessed separately at the level of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Since 2004 the Commonwealth Fund has produced surveys, "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall", comparing the performance of health systems in 11 wealthy countries in which the UK generally ranks highly. In the 2021 survey the NHS dropped from first overall to fourth as it had fallen in key areas, including 'access to care and equity.'[67] The Euro Health Consumer Index attempted to rank the NHS against other European health systems from 2014 to 2018. The right-leaning[68] think tank Civitas produced an International Health Care Outcomes Index in 2022 ranking the performance of the UK health care system against 18 similar, wealthy countries since 2000. It excluded the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as data stopped in 2019. The UK was near the bottom of most tables except households who faced catastrophic health spending.[69]

A comparative analysis of health care systems in 2010, by The Commonwealth Fund, a left-leaning US health charity, put the NHS second in a study of seven rich countries.[70][71] The report put the United Kingdom health systems above those of Germany, Canada and the United States; the NHS was deemed the most efficient among those health systems studied.

A 2018 study by the King's Fund, Health Foundation, Nuffield Trust, and the Institute for Fiscal Studies to mark the NHS 70th anniversary concluded that the main weakness of the NHS was healthcare outcomes. Mortality for cancer, heart attacks and stroke, was higher than average among comparable countries. The NHS was doing well at protecting people from heavy financial costs when ill. Waiting times were about the same, and the management of longterm illness was better than in other comparable countries. Efficiency was good, with low administrative costs and high use of cheaper generic medicines.[72] Twenty-nine hospital trusts and boards out of 157 had not met any waiting-time target in the year 2017–2018.[73] The Office for National Statistics reported in January 2019 that productivity in the English NHS had been growing at 3%, considerably faster than across the rest of the UK economy.[74]

In 2019, The Times, commenting on a study in the British Medical Journal, reported that "Britain spent the least on health, £3,000 per person, compared with an average of £4,400, and had the highest number of deaths that might have been prevented with prompt treatment". The BMJ study compared "the healthcare systems of other developed countries in spending, staff numbers and avoidable deaths".[75]

Over 130,000 deaths since 2012 in the UK could have been prevented if progress in public health policy had not stopped due to austerity, analysis by the Institute for Public Policy Research found. Dean Hochlaf of the IPPR said: "We have seen progress in reducing preventable disease flatline since 2012."".[76] The key NHS performance indicators (18 weeks (RTT), 4 hours (A&E) and cancer (2 week wait) have not been achieved since February 2016, July 2015 and December 2015 respectively.[77]

A ranking of individual hospitals around the world, published by Newsweek in March 2022, no NHS hospital was listed within the top 40. St Thomas' Hospital was ranked at 41, followed by University College Hospital at 54, and Addenbrooke's Hospital at 79.[78]

Overall satisfaction with the NHS in 2021 fell, more sharply in Scotland than in England, 17 points to 36% – the lowest level since 1997 according to the British Social Attitudes Survey. Dissatisfaction with hospital and GP waiting times were the biggest cause of the fall.[79]

The NHS Confederation polled 182 health leaders and 9 in 10 warned that inadequate capital funding harmed their "ability to meet safety requirements for patients" in health settings including hospitals, ambulance, community and mental health services and GP practices.[80]

Public perception of the NHS

[edit]In 2016 it was reported that there appeared to be support for higher taxation to pay for extra spending on the NHS as an opinion poll in 2016 showed that 70% of people were willing to pay an extra penny in the pound in income tax if the money were ringfenced and guaranteed for the NHS.[81] Two thirds of respondents to a King's Fund poll, reported in September 2017, favoured increased taxation to help finance the NHS.[82]

A YouGov poll reported in May 2018 showed that 74% of the UK public believed there were too few nurses.[83]

The trade union, Unite, said in March 2019 that the NHS had been under pressure as a result of economic austerity.[84]

A 2018 public survey reported that public satisfaction with the NHS had fallen from 70% in 2010 to 53% in 2018.[85] The NHS is consistently ranked as the institution that makes people proudest to be British, beating the royal family, Armed Forces and the BBC.[86] One 2019 survey ranked nurses and doctors – not necessarily NHS staff – amongst the most trustworthy professions in the UK.[87]

In November 2022 a survey by Ipsos and the Health Foundation found just a third of respondents agreed the NHS gave a good service nationally, and 82% thought the NHS needed more funding. 62% expected care standards to fall during the following 12 months. Sorting out pressure and workload on staff and increasing staff numbers were the chief priorities the poll found. Improving A&E waiting times and routine services were also concerns.[88] Just 10% of UK respondents felt their government had the correct plans for the NHS. The Health Foundation stated in spite of these concerns, the public is committed to the founding principles of the NHS and 90% of respondents believe the NHS should be free, 89% believe NHS should provide a comprehensive service for everyone, and 84% believe the NHS should be funded mainly through taxation.[89]

Role in combating coronavirus pandemic

[edit]In 2020, the NHS issued medical advice in combating COVID-19 and partnered with tech companies to create computer dashboards to help combat the nation's coronavirus pandemic.[90][91] During the pandemic, the NHS also established integrated COVID into its 1-1-1 service line as well.[92] Following his discharge from the St. Thomas' Hospital in London on 13 April 2020 after being diagnosed with COVID-19, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson described NHS medical care as "astonishing" and said that the "NHS saved my life. No question."[93][94] In this time, the NHS underwent major re-organisation to prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic.[95]

On 5 July 2021, Queen Elizabeth II awarded the NHS the George Cross.[96] The George Cross, the highest award for gallantry available to civilians and is slightly lower in stature to the Victoria Cross, is bestowed for acts of the greatest heroism or most conspicuous courage. In a handwritten note the Queen said the award was being made to all NHS staff past and present for their "courage, compassion and dedication" throughout the pandemic.[97]

Hospital beds

[edit]In 2015, the UK had 2.6 hospital beds per 1,000 people.[98] In September 2017, the King's Fund documented the number of NHS hospital beds in England as 142,000, describing this as less than 50% of the number 30 years previously.[99] In 2019 one tenth of the beds in the UK were occupied by a patient who was alcohol-dependent.[100]

NHS music releases

[edit]The NHS have released various charity singles including:

- 2015: National Health Singers - "Yours"

- 2015: NHS Choir - "A Bridge Over You" (being a mashup of "Bridge Over Troubled Water" and "Fix You")

- 2018: NHS Voices - "With a Little Help from My Friends"

- 2018: National Health Singers - "NHS 70: Won't Let Go"

- 2020: NHS and keyworkers - "You'll Never Walk Alone"

See also

[edit]- History of the NHS England

- History of NHS Scotland

- History of NHS Wales

- National Care Service

- Private providers of NHS services

- Special health authority

- Criticism of the National Health Service (England)

- Manx Care

General

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sometimes used as a UK-wide logo for unofficial purposes. The three other national health services in the UK outside England have their own logos and names.

References

[edit]- ^ "NHS Identity Guidelines | NHS logo". www.england.nhs.uk. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Health funding in Northern Ireland – Northern Ireland Affairs Committee – House of Commons".

- ^ Choices, NHS. "The principles and values of the NHS in England". www.nhs.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b "NHS entitlements: migrant health guide – Detailed guidance". UK Government. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Who can get free prescriptions". NHS. 9 November 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "10 truths about Britain's health service". Guardian. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ NHS Workforce Statistics - January 2024

- ^ Cowper, Andy (23 May 2016). "Visible and valued: the way forward for the NHS's hidden army". Health Service Journal. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Triggle, Nick (24 May 2018). "10 charts that show why the NHS is in trouble". Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Tombs, Robert (2014). The English and Their History. Vintage Books. p. 864.

- ^ "The UK has much to fear from a US trade agreement". www.newstatesman.com. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "An overview of NHS Procurement of Medicines and Pharmaceutical Products and Services for acute care in the United Kingdom" (PDF). www.sps.nhs.uk/. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "US takes aim at the UK's National Health Service". POLITICO. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Thomas-Symonds, Nick (3 July 2018). "70 years of the NHS: How Aneurin Bevan created our beloved health service". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Brian Abel-Smith, The Hospitals 1800–1948 (London, 1964), p. 229.

- ^ "Health Service debate". Labour Party. October 1934. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Beveridge, William (November 1942). "Social Insurance and Allied Services" (PDF). HM Stationery Office. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ White Paper – A National Health Service, YouTube.

- ^ Charles Webster, The Health Services since the War, Volume 1: Problems of Health Care, The National Health Service Before 1957 (London: HMSO, 1988), p. 399.

- ^ Ruth Barrington, Health, Medicine & Politics in Ireland 1900–1970 (Institute of Public Administration: Dublin, 1987) pp. 188–89.

- ^ Wales, NHS (23 October 2006). "NHS Wales | 1960's". www.wales.nhs.uk. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Delamothe, Tony (2008). "Founding Principles (31 May 2008)". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 336 (7655). British Medical Journal: 1216–1218. doi:10.1136/bmj.39582.501192.94. PMC 2405823. PMID 18511796.

- ^ Webster C. The National Health Service: a political history. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ^ "NHS Bill Second Reading". Hansard. 30 April 1946.

- ^ "Kingsfund, July 2013".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The NHS in England – About the NHS – NHS core principles". Nhs.uk. 23 March 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Paying for dental treatment in the UK". Oral Health Foundation. 16 January 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Kenneth O. Morgan, 'Aneurin Bevan' in Kevin Jeffreys (ed.), Labour Forces: From Ernie Bevin to Gordon Brown (I.B. Taurus: London & New York, 2002), pp. 91–92.

- ^ "NHS prescription charges". politics.co.uk. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Martin Powell and Robin Miller, 'Seventy Years of Privatising the British National Health Service?', Social Policy & Administration, vol. 50, no. 1 (January 2016), pp. 99–118.

- ^ Adams, Ryan (27 July 2012). "Danny Boyle's intro on Olympics programme". Awards Daily. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ a b c "Check if your immigration status lets you get free healthcare". Citizens Advice. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ Ross, Graeme (24 February 2016). "Eligibility for NHS Treatment". www.hr.admin.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ Kilic Y, Korolewicz J, Stein A. What is the NHS?

- ^ "Categories of exemption – Healthcare in England for visitors – NHS Choices". NHS England. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ National Health Service (Charges to Overseas Visitors) Regulations 1989.

- ^ "Non-EEA country-by-country guide – Healthcare abroad". NHS Choices. 1 January 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "Get temporary cover for emergency treatment abroad (Provisional Replacement Certificate) | NHSBSA". www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "How to access NHS services in England if you are visiting from abroad". nhs.uk. 9 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Pay for UK healthcare as part of your immigration application". GOV.UK. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Pay for UK healthcare as part of your immigration application". GOV.UK. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b "The NHS Budget And How It Has Changed". The King's Fund. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "How is the NHS in Wales funded? | NHS Confederation". www.nhsconfed.org. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Annex A.1 – NHS Recovery, Health & Social Care". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Secretary announces 2023-24 Budget and contingency plans for governance". GOV.UK. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Chapter 4: NHS staff will get the backing they need". NHS Long Term Plan. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "NHS Workforce Statistics - February 2023 (Including selected provisional statistics for March 2023)". NHS Digital. 25 May 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "NHS Workforce Interactive Report". NHS Digital. 25 May 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Donnelly, Laura (23 July 2022). "UK's 'runaway' health spending costs £10k per household – but produces some of the worst results". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Wes Streeting says NHS is broken as he announces pay talks with junior doctors". The Guardian. 6 July 2024. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Iacobucci, Gareth (12 July 2024). "Ara Darzi is charged with uncovering "hard truths" of NHS performance". BMJ. 386: q1552. doi:10.1136/bmj.q1552. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 38997127.

- ^ "Streeting appoints former New Labour minister to review NHS". Civil Service World. 11 July 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ "NHS faces staggering increase in cost of elderly care, academics warn", The Guardian.

- ^ Aguilar, Carmen (29 May 2018). "Brexit causes flight of European health workers from the NHS". VoxEurop/EDJNet. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Medical school places must double by 2030 to meet demand for doctors, college warns". GP Online. 25 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ 'Demoralised' nurses being 'driven out' of profession, RCN survey finds The Guardian. 6 June 2022

- ^ Hayward, Eleanor (1 June 2022). "GP shortage leaves doctors in some areas with 2,500 patients". The Times.

- ^ "Plan to train and retain more NHS doctors and nurses". BBC. 30 June 2023.

- ^ Evans, Tomos (23 September 2024). "Welsh and UK governments to 'work together' to cut NHS waiting lists". Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Campbell, Dennis (8 October 2018). "Delays in NHS mental health treatment 'ruining lives'". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Syal, Rajeev (9 October 2018). "Child mental health services will not meet demand, NAO warns". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Mind responds to NHS long term plan". www.mind.org.uk. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Quadri, Sami (11 August 2024). "NHS tells staff to ask men if they're pregnant during X-rays". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 12 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

Radiographers at several NHS hospitals have been instructed to ask all men aged 12 to 55 if they are pregnant before performing X-rays. The controversial policy, aimed at considering non-binary, transgender and intersex patients, has sparked outrage among patients and campaigners alike.

- ^ Searles, Michael (11 August 2024). "NHS staff told to ask men if they are pregnant before X-rays". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

But forms designed to be inclusive have caused confusion and anger among patients and pose a risk to their safety, radiographers told The Telegraph.

- ^ Wace, Charlotte (11 August 2024). "NHS radiographers told to check if men are pregnant". The Times & The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

Radiographers in multiple NHS hospitals have been advised to check if men are pregnant before conducting scans as part of inclusivity guidance.

- ^ Kingsley, Thomas (29 March 2022). "Hospital is asking men if they're pregnant before taking scans". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "The NHS has never been the 'envy of the world'". Spectator. 5 August 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Johnston, Philip (7 April 2014). "A close encounter with the property boom". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Knox, Tim. "International Health Care Outcomes Index 2022" (PDF). Civitas. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "UK health system is top on "efficiency", says report". BBC News. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Davis, Karen; Cathy Schoen and Kristof Stremikis (23 June 2010). "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, 2010 Update". The Commonwealth Fund. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "How good is the NHS?" (PDF). Kings Fund. July 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "The hospitals that fail to treat patients on time", BBC.

- ^ "Public service productivity: healthcare, England: financial year ending 2017". 9 January 2019.

- ^ Blakely, Rhys (28 November 2019). "NHS spends least on patient health". The Times: 25.

- ^ "Austerity to blame for 130,000 'preventable' UK deaths – report", The Guardian.

- ^ Stein A, Kilic Y, Korolewicz J. What is the NHS's performance?[permanent dead link]

- ^ "World's Best Hospitals 2022". Newsweek. March 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "View grows that NHS 'must live within its means' as satisfaction plummets". Health Service Journal. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Rundown NHS hospitals have become a danger to patients, warn health chiefs The Guardian

- ^ Mason, Rowena (30 December 2016). "People may be ready to pay extra penny on tax for NHS, Tim Farron says". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Denis (16 September 2017). "Two-thirds support higher taxes to maintain NHS funding". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Triggle, Nick (13 May 2018). "Three-quarters of public worried about nurse staffing". BBC. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ NHS public satisfaction dip due to government austerity policies, says Unite. 7 March 2019

- ^ "Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2018". The King's Fund. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Team, Mintel Press. "The NHS tops list of UK's most cherished institutions". Mintel. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "Advertising execs rank below politicians as Britain's least-trusted profession". Ipsos MORI. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Public support for UK government's handling of NHS in England drops to new low Sky News

- ^ 9 in 10 disagree with government's handling of NHS in new low, poll reveals The Independent

- ^ Advice for everyone-Coronavirus (COVID-19) www.nhs.uk, accessed 12 April 2020.

- ^ Kellon, Leo (28 March 2020). "Coronavirus: NHS turns to big tech to tackle Covid-19 hot spots". BBC News. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Check if you have coronavirus symptoms 111.nhs.uk, accessed 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Boris Johnson says NHS saved his life after leaving hospital – video". The Guardian. 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Boris Johnson thanks NHS staff for coronavirus treatment". BBC News. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Rimmer MP, Al Wattar BH, on behalf of the UKARCOG Members. Provision of obstetrics and gynaecology services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of junior doctors in the UK National Health Service. BJOG 2020; https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16313.

- ^ "Queen gives George Cross to NHS for staff's 'courage and dedication'". BBC News. 5 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Emma.Goodey (4 July 2021). "The Queen awards the George Cross to the UK's National Health Services". The Royal Family. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ NHS statistics, facts and figures Archived 7 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine 14 July 2017 www.nhsconfed.org, accessed 14 March 2020.

- ^ NHS hospital bed numbers: past, present, future 29 September 2017 www.kingsfund.org.uk, accessed 14 March 2020.

- ^ Boseley, Sarah (4 July 2019). "New report reveals staggering cost to NHS of alcohol abuse". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Brady, Robert A. Crisis in Britain. Plans and Achievements of the Labour Government (1950) pp. 352–41 excerpt

- Gorsky, Martin. "The British National Health Service 1948–2008: A Review of the Historiography," Social History of Medicine, Dec 2008, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp. 437–60

- Hacker, Jacob S. "The Historical Logic of National Health Insurance: Structure and Sequence in the Development of British, Canadian, and U.S. Medical Policy," Studies in American Political Development, April 1998, Vol. 12 Issue 1, pp. 57–130.

- Hilton, Claire. (26 August 2016). Whistle-blowing in the National Health Service since the 1960s History and Policy. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Loudon, Irvine, John Horder and Charles Webster. General Practice under the National Health Service 1948–1997 (1998) online Archived 23 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Rintala, Marvin. Creating the National Health Service: Aneurin Bevan and the Medical Lords (2003) online Archived 18 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- Rivett G. C. From Cradle to Grave: The First 50 (65) Years of the NHS. King's Fund, London, 1998 now updated to 2014 and available at www.nhshistory.co.uk

- Stewart, John. "The Political Economy of the British National Health Service, 1945–1975: Opportunities and Constraints", Medical History, October 2008, Vol. 52, Issue 4, pp. 453–70.

- Webster, Charles. "Conflict and Consensus: Explaining the British Health Service", Twentieth Century British History, April 1990, Vol. 1 Issue 2, pp. 115–51

- Webster, Charles. Health Services Since the War. Vol. 1: Problems of Health Care. The National Health Service before 1957 (1988) 479pp online Archived 19 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Official website of the NHS in England

- Official website of NHS Scotland

- Official website of NHS Wales

- Official website of Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland