Elena Glinskaya

| Elena Glinskaya | |

|---|---|

| |

| Regent of Russia | |

| Regency | 4 December 1533 – 4 April 1538 |

| Monarch | Ivan IV |

| Grand Princess consort of Moscow | |

| Tenure | 21 January 1526 – 4 December 1533 |

| Predecessor | Solomonia Saburova |

| Successor | Anastasia Romanovna |

| Born | c. 1510 |

| Died | 4 April 1538 (age 27–28) |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Ivan Vasilyevich Yuri Vasilevich |

| House | Glinski Rurik (by marriage) |

| Father | Vasili Lvovich Glinsky |

| Mother | Ana Jakšić |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox |

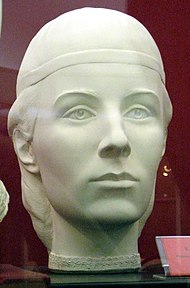

Elena Vasilyevna Glinskaya (Russian: Елена Васильевна Глинская; c. 1510 – 4 April 1538) was the grand princess consort of Moscow as the second wife of Vasili III of Russia, and de facto regent of Russia from 1533 until her death in 1538. She was the mother of the first crowned tsar Ivan IV.[1][2]

Biography

[edit]Marriage

[edit]Elena was born in 1510 as the daughter of Prince Vasili Lvovich Glinsky (d. 1515), a member of a Lipka Tatar clan claiming descent from the Mongol ruler Mamai, and Serbian Princess Ana Jakšić from the Jakšić noble family. It is to her powerful uncle, Prince Mikhail Lvovich Glinsky, that the family owed its distinction. In 1525, Vasili III resolved to divorce his infertile wife, Solomoniya Saburova, and marry Elena. According to the chronicles, he chose Elena "because of the beauty of her face and her young age."[3] Despite strong opposition from the Russian Orthodox Church, the divorce was effected.[4] They were married on 21 January 1526.[5]

Elena gave birth to two sons – Ivan Vasilyevich (future Ivan the Terrible) in 1530 and Yuri Vasilievich (future Prince Yuri of Uglich) in 1532.[6] It was later rumoured, that she brought witches from Finland and people of the Sami to help her conceive by the help of magic[7]

Regency

[edit]On his deathbed, Vasili III transferred his powers to her until their oldest son Ivan, who was only 3 at the time, was mature enough to rule the country.[8] The chronicles of those times do not provide any more or less precise information on her legal status after Vasili's death. All that is known is that it could be defined as regency and that the boyars had to report to her. That is why the time between Vasili's death on 3 December 1533 and her own demise in 1538 is called the Reign of Elena. She challenged the claims of her brothers-in-law, Yury Ivanovich and Andrey of Staritsa. The struggle ended with their incarceration in 1534 and 1537, respectively.[7]

Elena was a very capable stateswoman. In 1535, she carried out a currency reform that introduced a unified monetary system in the state. In foreign affairs, she succeeded in signing an armistice with Lithuania in 1536, while simultaneously neutralizing Sweden. She had a new defensive wall constructed around Moscow, invited settlers from Lithuania, bought Russian prisoners free and instigated measures to protect travellers against street bandits. She is also recorded as having visited several convents. In a negative note, her reign was infamous for conflicts inside the government caused by her close association with a handsome young boyar named Ivan Feodorovich Ovchina-Telepnev-Obolensky and the Metropolitan Daniel.[7]

Elena died in 1538 at a relatively young age. Her son's governess, Agrippina Fedorovna Chelyadnina, was arrested in connection with Elena's death. Some historians believe that Elena was poisoned by the Shuiskys, who usurped power after her death. Recent studies of her remains tend to support the thesis that she was poisoned.[9][1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Pushkareva, Natalia (1997). Women in Russian History: From the Tenth to the Twentieth Century. Armonk, NY: M.E.Sharpe. pp. 65–58. ISBN 9780765632708.

- ^ Payne, Robert; Romanoff, Nikita (2002) [1975]. Ivan the Terrible. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 9780815412298.

- ^ Smith, Bonnie G. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History.

- ^ Martin, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Smith, Bonnie G. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History.

- ^ Martin, pp. 292–293.

- ^ a b c Isabel de Madariaga (in Swedish) : Ivan den förskräcklige ("Ivan the Terrible") (2008)

- ^ Martin, p. 293.

- ^ Martin, p. 331

Sources

[edit]- Martin, Janet (1995). Medieval Russia 980-1584. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521368322.