Woodlawn, Chicago

Woodlawn | |

|---|---|

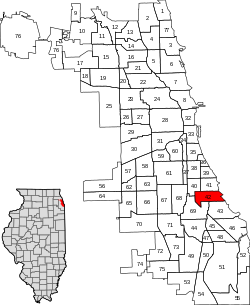

| Community Area 42 - Woodlawn | |

The Strand Hotel, a NRHP listed apartment hotel on Cottage Grove Avenue. | |

Location within the city of Chicago | |

| |

| Coordinates: 41°46.8′N 87°36′W / 41.7800°N 87.600°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| City | Chicago |

| Neighborhoods | List

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.07 sq mi (5.36 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 24,425 |

| • Density | 12,000/sq mi (4,600/km2) |

| Demographics 2020[1] | |

| • White | 8.2% |

| • Black | 82.3% |

| • Hispanic | 2.9% |

| • Asian | 3.4% |

| • Other | 3.3% |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | parts of 60637 |

| Median household income 2018 | $26,415[1] |

| Source: U.S. Census, Record Information Services | |

Woodlawn is a neighbhorhood on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, located on and near the shore of Lake Michigan 8.5 miles (13.7 km) south of the Loop. It is one of the city's 77 municipally recognized community areas. It is bounded by the lake to the east, 60th Street to the north, King Drive to the west, and 67th Street to the south, save for a small tract that lies south of 67th Street between Cottage Grove Avenue and South Chicago Avenue. Local sources sometimes divide the neigborhood along Cottage Grove into "East" and "West Woodlawn."

Woodlawn contains a large portion of Jackson Park, including the site of the under-construction Barack Obama Presidential Center. The neighborhood is also home to a number of educational institutions: Hyde Park Career Academy, Mount Carmel High School, Chicago Theological Seminary, and the southern portion of the campus of the University of Chicago—including the Law School, the Harris School of Public Policy, the School of Social Service Administration, and the University of Chicago Press.

Demographics

[edit]Present-day Woodlawn is a predominantly African-American neighborhood. Per 2020 U.S. census data, the neighborhood's racial makeup is 79.8% Black, 10.1% white, 3.6% Asian, and 3.1% Hispanic, with an additional 3.1% belonging to two or more races. There are demographic differences within Woodlawn, however: West Woodlawn is about 95% African-American, while East Woodlawn is significantly more diverse. The median household income in the neighborhood is $32,189, with 31.17% of residents living below the poverty line.[2]

History

[edit]Racial transition

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 66,052 | — | |

| 1940 | 71,685 | 8.5% | |

| 1950 | 80,699 | 12.6% | |

| 1960 | 81,279 | 0.7% | |

| 1970 | 53,820 | −33.8% | |

| 1980 | 36,323 | −32.5% | |

| 1990 | 27,473 | −24.4% | |

| 2000 | 27,086 | −1.4% | |

| 2010 | 25,983 | −4.1% | |

| 2020 | 24,425 | −6.0% | |

| [1] | |||

Up until 1948, Woodlawn was a middle class, white neighborhood, which grew out of the floods of workers and commerce from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. During the first half of the century, many University of Chicago professors lived in Woodlawn. With the Supreme Court ruling outlawing racially restrictive covenants in 1948, the combination of the expanding African American urban population, their limited housing options, and exploitive real estate maneuvers that divided up apartments into kitchenettes, Woodlawn began to have its first African American residents.[citation needed] Cayton and Drake described the anxieties and clashes that took place at the edge of the ghetto in Black Metropolis. The play A Raisin in the Sun is based on the experiences of author Lorraine Hansberry and her family, who were among the first to move in.

Like other communities bordering the ghetto, Woodlawn experienced intense bouts of white flight when the first African Americans moved into the neighborhood (especially the Washington Park Subdivision). Many institutions and people moved to the suburbs, a process that was facilitated by new federal housing loans. This combination of white flight from large apartments and high housing demand of the incoming African American population often proved lucrative for realtors, who routinely subdivided the vacated apartments. From this, buildings were over-filled with families. Absentee landlords seldom did much to maintain the buildings.[citation needed]

Others attempted to integrate this area but met with limited success. For example, the First Presbyterian Church (6400 South Kimbark Avenue) integrated in 1954 and, by the 1960s, had a markedly mixed character. However, older members often felt put out by the demographic and "cultural" changes that came with integration, and by the mid-1960s, the Church's finances and membership rates were in trouble. For better or for worse, there had been an across the board change in the community.[citation needed]

1960s

[edit]By the early 1960s, Woodlawn was a predominantly African-American neighborhood with a population of over 80,000 people. 63rd Street was one of the busiest streets on the South Side and was famous for its jazz clubs. Despite its bustle, Woodlawn was an economically deteriorating community, and attempts to revive its citizenry were short-lived and fractured. The community escaped the riots that devastated the West Side after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. mainly because of the works of the Black P. Stone Nation in 1968. Nevertheless, most business owners fled. A rash of arsons destroyed a reported 362 abandoned buildings between 1968 and 1971.[3]

The University of Chicago

[edit]In Hyde Park to the north, similar demographic and racial changes began in the 1950s but with radically different results. The University of Chicago, a large land owner with vested interest in the character of the neighborhood, fought through many avenues against what it saw as the encroachment of blight.

As Arnold Hirsch argues in his chapter "Neighborhood on a hill" in Making the Second Ghetto, the University, through the SECC and, at times, with brute force, made Hyde Park the site of one of the first "urban renewal" projects in the country. In an attempt to maintain the number of white families, the University tore down "slum" areas, often employing eminent domain powers. In the process, many African Americans were displaced from Hyde Park, and cultural centers like 55th Street were leveled.

After their success in Hyde Park, the University moved quickly to begin a second urban renewal project in Woodlawn. A one mile wide area from 60th to 61st in Woodlawn was scheduled for renewal and the University's planned South Campus. The plans were drawn, there was a press conference, and the campus was eventually constructed.[citation needed]

At one time, the University of Chicago Law School raised more than $10,000 each year for charitable support for the children of Woodlawn. In 1999, however, it eliminated that support and shifted the funding to student scholarships for public interest jobs primarily outside the Chicago area.[4]

Community organizations

[edit]TWO (The Woodlawn Organization)

[edit]The Woodlawn Organization coalesced around the perception that the University would pursue a land use policy in Woodlawn as it did in Hyde Park, and it has its roots in the pastors' Alliance of Woodlawn. Several years earlier, the Alliance had called in Saul Alinsky, founder of the Industrial Areas Foundation, to discuss plans to organize the community. But several major members of the Alliance at that time were displeased with Alinsky's brashness and controversial direct tactics. In the initial years, when TWO was still under the IAF umbrella, Nicholas Von Hoffman, Alinsky's second in command, planned most of the actions. After the University's plans were known, several prominent churches gave the seed money for the organization, which began in 1961.

TWO, like other IAF organizations, was a coalition of existing community entities such as churches, business and civic associations. These member groups paid dues, and the organization was run by an elected board. The TWO moved quickly to establish itself as the "voice" of Woodlawn, mobilizing existing leadership and bringing up new leadership. A prime example of the newly empowered leadership in TWO was Reverend Arthur M. Brazier, who was the first spokesperson and eventual president. Brazier started out as a mail carrier, became a preacher in a store front church, and then, through TWO, burgeoned into a national spokesman for the black power movement. Brazier became a very powerful pastor in Chicago.

As Fish argues in Black Power/White Control TWO picked issues that mobilized resident participation, and at the same time built power for the organization to take on large outside entities like the University and the City (i.e. Mayor Daley). The group took part in the flurry of activity surrounding the Freedom Rides and the Civil Rights Movement by loading up over 40 buses of people from Woodlawn and riding to City Hall to register to vote. They also rallied against slum landlords and cheating business owners. TWO also took action on the University and were able to gain a seat on the City planning board (which stopped the University's plans[citation needed]).

TWO faced continually worsening conditions in the neighborhood, and there are many arguments about its efficacy. Especially controversial was Brazier's opposition to a planned and nearly completed Green Line extension to Dorchester, which forced the Chicago Transit Authority to tear down the nearly completed station and the tracks east of the Cottage Grove terminal and forfeit millions of dollars in federal funds in 1996.[citation needed]

Woodlawn East Community And Neighbors Inc.

[edit]As TWO moved to consolidate its position as the Voice of Woodlawn, other community organizations arose to deal with specific issues of housing and community empowerment, such as the arson fires that destroyed hundreds of buildings in Woodlawn in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Perhaps the most prominent of these organizations is Woodlawn East Community And Neighbors Inc. (WECAN)[5] founded by Mattie C. Butler, a 40-year Woodlawn resident and sister of Hall of Fame R&B singer/current Cook County Commissioner Jerry Butler.

Butler founded WECAN in October 1980 after watching 13 children die in an arson fire in a building next door to her home.[6] WECAN quickly became a neighborhood and citywide advocate for rescuing at-risk and abandoned buildings, preserving an estimated 5000 units of housing in Woodlawn since its founding. Many of its programs - Abandoned Property Program, Vintage Homes For Chicago, Step-Up Housing - have become citywide models. WECAN was a founding member of the citywide Chicago Rehab Network of community developers. The organization and its founder, Mattie C. Butler, have been honored with local and national awards including the 1989 Petra Foundation Award[7] and the 2008 Community Empowerment Advocate of the Year Award.

As the focus of development in Woodlawn has shifted toward new construction and condo conversion, WECAN is seen as a vocal advocate for affordable housing for low-moderate income residents and especially seniors. That stance has on occasion brought the organization into conflict with other groups in Woodlawn, particularly TWO, who have pushed for new development at what WECAN sees as the expense of current residents. WECAN led the opposition to the teardown of the 63rd Street CTA elevated line, a battle it lost. Woodlawn has one of the highest foreclosure rates in the city and is particularly affected by foreclosures of apartment buildings and condominium conversions.[citation needed]

WECAN sits on the New Communities Program Executive Steering Committee, operates 132 units of affordable housing, and operates supportive services, after school programs and its Housing Resource Center.[citation needed]

Project Brotherhood

[edit]Project Brotherhood is a health clinic focused on using community outreach and preventive education to meet the needs and improve the health of African American men in the Woodlawn area. The clinic is operated by a combination of staff, volunteers, and interns and hosts a variety of free services for members of the community. In the CNN documentary "Black in America 2", Project Brotherhood was presented as one of America's pioneers in terms of African American health.[8]

Gangs

[edit]In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jeff Fort and Eugene Hairston ran a small gang of neighborhood kids centered near 66th and Blackstone called the Blackstone Rangers. By the mid 1960s, Fort and Hairston had pulled together twenty-one other local street gangs, thus becoming the dominant gang on Chicago's South Side, engaging in numerous criminal activities while maintaining a political activist facade.[9] For example, in 1966, in the midst of a violent drive to consolidate power and intimidate rivals, the Rangers provided security as Dr. Martin Luther King and the Congress On Racial Equality marched through hostile white neighborhoods like Cicero and Marquette Park.[10]

Under the influence of both the Black Nationalist movement and the nonviolent civil rights movement, they changed their name to "The Black Peace Stone Nation". During the riots in the aftermath of Dr. King's assassination, the "Stones" were credited with preserving and protecting the Woodlawn neighborhood (albeit through extortion and intimidation),[11][12] which saw minimal disturbance in contrast with neighborhoods like Garfield Park and the West Side.

Over time, the ties with the nonviolence movement faded as the gang's name was altered to "Black P. Stone Nation" Hairston's incarceration led Jeff Fort to take sole leadership of the gang, which by then stretched across numerous neighborhoods of the city and boasted as many as 50,000 members. During this time, the Stones became more political and more involved in community power structure. It even received funding from the US Office Of Economic Opportunity to run a job-training program in Woodlawn, the pilfering of which led Fort to another prison sentence.

While jailed, Fort was influenced by the Nation of Islam and upon his release renamed the gang again, to the El Rukn Tribe Of The Moorish Science Temple of America, usually shortened to El Rukns. The gang, whose home territory is in between the "-Stone streets" of Blackstone Avenue and Stony Island Avenue, are still a very strong force in the Woodlawn community.

Present-day Woodlawn

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (June 2008) |

The area between 59th and 60th Streets is known as the Midway Plaisance, incorporating Midway Plaisance North (south of 59th Street) and Midway Plaisance South, north of 60th Street. Now dominated by a green space of low valleys, the Plaisance is widely known as the site of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, in which the green space was to be designated as the Fair location (but was never utilized). The Plaisance is now a well-maintained walking and bike riding thoroughfare amidst the University's campuses. Between 60th and 61st Streets (with Stony Island Avenue to the east and Cottage Grove Avenue to the west) are several of the University's South Campus buildings including: University of Chicago Press, the law quadrangle and law library, the School of Social Service Administration, the Harris School of Public Policy Studies, the National Opinion Research Center, the Center for Research Libraries, Chapin Hall, and Granville-Grossman Residential Commons. Some of the University's faculty and several hundred of its graduate and undergraduate students live south of 60th Street in University-owned real estate and dormitories, as well as in privately owned residences.

To replace the decaying Shoreland Hotel, the University of Chicago constructed a new residence hall on the corner of 61st St. and Ellis, designed with input from residents of both Hyde Park and Woodlawn so as to minimize possible alienation of the neighboring community.

Jackson Park

[edit]Jackson Park is a 500-acre (2 km2) park on Lake Michigan in the neighborhoods of Woodlawn, Hyde Park, and bordering South Shore.

The land for Jackson Park was set aside in the 1870s. The area was originally a "rough, tangled stretch of bog and dune" until it was transformed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect of New York City's Central Park. The park is connected by the Midway Plaisance to Washington Park on Woodlawn's North end.

Jackson Park was the site of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. For this event, hundreds of acres of undeveloped park was turned into the spectacular, but temporary, Beaux-Arts "White City." A small number of structures built for or used during the fair still remain in the park.

Attractions inside Jackson Park include Osaka Garden, the Jackson Park Golf Course, Jackson Park Harbor, Wooded Isle, the gilded Daniel Chester French statue Republic (a replica of a much larger statue built for the Columbian Exposition), several lagoons, and the 63rd Street Beach with its magnificent beach house.

Education

[edit]It is within Chicago Public Schools. Emmett Till Math & Science Academy is in Woodlawn.[13] Emmett Till, its namesake, was an alumnus of the school when it was called James McCosh Elementary School; in that period all of its students were African-American.[14] It was given its current name in 2006.[15]

Notable people

[edit]- Dayvon Daquan Bennett (1994–2020), alias "King Von", rapper and songwriter[16]

- Arthur M. Brazier (1921–2010), pastor and activist

- Ernest Burgess (1886–1966), urban sociologist and formulator of the concentric zone model. He resided at 6140 South Drexel Avenue at the time of his death.[17]

- Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), American poet and teacher, and the first African American to receive a Pulitzer Prize.[18][19]

- Jesse Brown (1944–2002), 2nd United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs. He was a childhood resident living in Woodlawn near East 63rd Street and South Ingleside Avenue.[20]

- Robert Conrad (1935-2020), actor

- Clarence Darrow (1857–1938), attorney, resided at 1537 East 60th Street for most of his adult life[21]

- Walter Eckersall (1886–1930), football official and sportswriter[22]

- Hamlin Garland (1860–1940), author

- Sam Greenlee (1930–2014), author. He was raised in the western area of Woodlawn.[23]

- Herbie Hancock (born 1940), musician

- Carl Augustus Hansberry (1895–1946), real estate broker and political activist; he was the plaintiff in Hansberry v. Lee, which stemmed from his effort to live in the Washington Park Subdivision[24][25]

- Lorraine Hansberry (1930–1965), playwright; her father Carl moved the family to the neighborhood's Washington Park Subdivision when she was eight years old[26]

- Hugh Hefner (1926–2017), magazine publisher, resided at 6052 South Harper Avenue when he produced the first copy of Playboy[27]

- Richard Hunt (born 1935), lived at 6324 S Eberhart Ave from birth until four years of age.[28]

- Mae Jemison (born 1956), physician and former NASA astronaut. She was a childhood resident of Woodlawn prior to her family's move to Morgan Park.[29]

- John Joseph Kelly (1898–1957), United States Marine who was awarded Medals of Honor from both the Army and Navy for his actions on October 13, 1918, at the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge during World War I. He was a childhood resident of 6558 South Ellis Avenue.[30][31]

- Richard Kiley (1922–1999), Tony-winning actor[32]

- Joe Louis (1914–1981), professional boxer and world heavyweight champion 1937–1949. He resided at the Wedgewood Hotel on the corner of East 64th Street and South Minerva Avenue for a time.[33]

- Charles Edward Merriam (1874–1953), professor of political science at the University of Chicago

- Minnie Miñoso (1925–2015), professional baseball player. He resided at the Wedgewood Hotel on the corner of East 64th Street and South Minerva Avenue for a time.[33]

- Jesse Owens (1913–1980), four-time gold medalist in the 1936 Olympic Games in track and field

- Henry J. Schlacks (1867–1938), architect

- Seymour Stedman (1871–1948), attorney and founding member of the Socialist Party of America. He resided at 6630 South Minerva Avenue.[34]

- Bill Veeck (1914-1986), Major League Baseball team owner & promoter, St. Louis Browns, Cleveland Indians, Chicago White Sox

- James H. Wilkerson (1869–1948), U.S. district judge who presided over the 1931 Al Capone tax-evasion trial

Gallery

[edit]-

"Black youngsters cool off with fire hydrant water on Chicago's South Side in the Woodlawn community. The kids don't go to the city beaches and use the fire hydrants to cool off instead. It's a tradition in the community, comprised of very low income people. The area has high crime and fire records. From 1960 to 1970 the percentage of Chicago blacks with income of $7,000 or more jumped from 26% to 58%." - June 1973. Photograph by John H. White

-

Hotel Mira Mar, at 6212-22 Woodlawn Avenue (photographed 1927)

-

Hyde Park High School, located at 62nd Street and Stony Island Avenue (photographed 2014)

-

Pre-1980 road sign, located at the south end of Cornell Drive near Stony Island Avenue and 65th Place (photographed 2018)

-

The Washington Park National Bank Building, at 6300 S. Cottage Grove (photographed 2020)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Community Data Snapshot - Woodlawn" (PDF). cmap.illinois.gov. MetroPulse. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Woodlawn". Chicago Health Atlas. Chicago Department of Public Health. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Woodlawn". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ See Spring 1999 issues of The Phoenix, the University of Chicago Law School's student newspaper, on file in the Lauinger Library at 1111 S. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637, but not available online.

- ^ "We Can Wood & Lawn – DIY Tips and Tricks for Lawn and Tree Care". Wecanwoodlawn.org. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ "The University of Chicago Magazine". Uchicago.edu. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ "The Petra Foundation". Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ "BIA update: Project Brotherhood". CNN. Cable News Network, Inc., A Time Warner Company. February 24, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Will Cooley, "'Stones Run It': Taking Back Control of Organized Crime in Black Chicago, 1940-1975," Journal of Urban History 37:6 (November, 2011), 911-932.

- ^ "The Blackstone Rangers | AREA|chicago". Archived from the original on December 6, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Chicago April 1968 Oral History Project | AREA|chicago". Archived from the original on August 16, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr". Uic.edu. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ "Home". Emmett Till Math & Science Academy. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

6543 South Champlain Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

- ^ "Who was Emmett Till?". PBS. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Chicago elementary school renamed for Emmett Till". Chicago Daily Journal. Associated Press. February 25, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Maxwell (August 18, 2021). "King Von Mural Near Parkway Gardens Sparked Debate, Threats And Harassment. Now, Neighbors To Vote On Its Fate". Block Club Chicago. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ "E. W. Burgess, 80, U. C. Teacher, Dies". Chicago Tribune. December 28, 1966 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Frost? Williams? No, Gwendolyn Brooks". www.pulitzer.org. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Watkins, Mel (December 4, 2000). "Gwendolyn Brooks, Whose Poetry Told of Being Black in America, Dies at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

Gwendolyn Brooks, who illuminated the black experience in America in poems that spanned most of the 20th century, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1950, died yesterday at her home in Chicago. She was 83.

- ^ Locin, Mitchell (December 18, 1992). "'I was just one of the 300,000': Vietnam wound a turning point for choice to head VA". Chicago Tribune. p. N22 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Schmidt, John R. (December 17, 2012). "A forgotten home of Clarence Darrow". WBEZ. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Collins, Charles (December 5, 1954). "Football's famous Walter Eckersall!". Chicago Sunday Tribune. (Chicago Tribune Magazine). p. 36.

- ^ Rosalind Cummings, "Local Lit: the relaxed rage of Sam Greenlee", Chicago Reader, April 14, 1994.

- ^ Fuller, Hoyt W. (December 1961). Johnson, John H. (ed.). "Earl B. Dickerson:warrior and statesman". Ebony. 17 (2). Chicago, Illinois: Johnson Publishing Company, Inc.: 153.

- ^ Wilkins, Roy, ed. (December 1940). "Supreme court upsets Chicago covenant case". Crisis. 47 (11). New York, New York: Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 390.

- ^ Koziarz, Jay (June 25, 2019). "Chicago Pride: 10 historic LGBTQ sites to visit". Curbed. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- ^ Rumore, Kori (September 27, 2017). "A Playboy's guide to Hugh Hefner's Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Introduction by Courtney J. Martin. Text by John Yau, Jordan Carter, LeRonn Brooks. Interview by Adrienne Childs. (2022). Richard Hunt. GREGORY R. MILLER & CO. ISBN 9781941366448.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rybarczyk, Tom; Rucker, Patrick (November 27, 2004). "Charlie Jemison, 78". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "John J. Kelly, Medal of Honor Marine, Is Home". Chicago Daily Tribune. May 9, 1919 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Kelly, John J. Private, USMC, (1898-1957)". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ Vallance, Tom (March 11, 1999). "Obituary: Richard Kiley". The Independent. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Spula, Ian (August 12, 2012). "Cornerspotted: The Wedgewood Hotel At Woodlawn & 64th". Chicago Curbed. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Atty. Seymour Stedman, 78, Dies at S. Side Home". Chicago Tribune. July 10, 1948.

External links

[edit]- Official City of Chicago Woodlawn Community Map

- The Woodlawn Project (University of Maryland School of Public Health)

- Woodlawn Community Collection (Black Metropolis Research Consortium, University of Chicago)