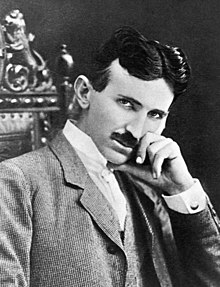

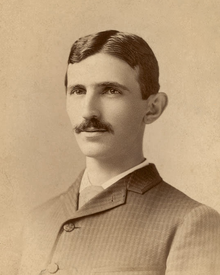

Nikola Tesla

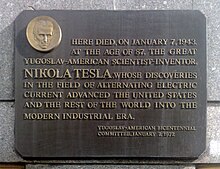

Nikola Tesla (/ˈnɪkələˈtɛslə/;[2] Serbian Cyrillic: Никола Тесла, [nǐkola têsla]; 10 July 1856 – 7 January 1943) was a Serbian-American[3][4] engineer, futurist, and inventor. He is known for his contributions to the design of the modern alternating current (AC) electricity supply system.[5]

Born and raised in the Austrian Empire, Tesla first studied engineering and physics in the 1870s without receiving a degree. He then gained practical experience in the early 1880s working in telephony and at Continental Edison in the new electric power industry. In 1884 he immigrated to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen. He worked for a short time at the Edison Machine Works in New York City before he struck out on his own. With the help of partners to finance and market his ideas, Tesla set up laboratories and companies in New York to develop a range of electrical and mechanical devices. His AC induction motor and related polyphase AC patents, licensed by Westinghouse Electric in 1888, earned him a considerable amount of money and became the cornerstone of the polyphase system which that company eventually marketed.

Attempting to develop inventions he could patent and market, Tesla conducted a range of experiments with mechanical oscillators/generators, electrical discharge tubes, and early X-ray imaging. He also built a wirelessly controlled boat, one of the first ever exhibited. Tesla became well known as an inventor and demonstrated his achievements to celebrities and wealthy patrons at his lab, and was noted for his showmanship at public lectures. Throughout the 1890s, Tesla pursued his ideas for wireless lighting and worldwide wireless electric power distribution in his high-voltage, high-frequency power experiments in New York and Colorado Springs. In 1893, he made pronouncements on the possibility of wireless communication with his devices. Tesla tried to put these ideas to practical use in his unfinished Wardenclyffe Tower project, an intercontinental wireless communication and power transmitter, but ran out of funding before he could complete it.

After Wardenclyffe, Tesla experimented with a series of inventions in the 1910s and 1920s with varying degrees of success. Having spent most of his money, Tesla lived in a series of New York hotels, leaving behind unpaid bills. He died in New York City in January 1943.[6] Tesla's work fell into relative obscurity following his death, until 1960, when the General Conference on Weights and Measures named the International System of Units (SI) measurement of magnetic flux density the tesla in his honor. There has been a resurgence in popular interest in Tesla since the 1990s.[7]

Early years

Nikola Tesla was born into an ethnic Serb family in the village of Smiljan, within the Military Frontier, in the Austrian Empire (present-day Croatia), on 10 July 1856.[9][10] His father, Milutin Tesla (1819–1879),[11] was a priest of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[12][13][14][15] His father's brother Josif was a lecturer at a military academy who wrote several textbooks on mathematics.[11]

Tesla's mother, Georgina "Đuka" Mandić (1822–1892), whose father was also an Eastern Orthodox Church priest,[16] had a talent for making home craft tools and mechanical appliances and the ability to memorize Serbian epic poems. Đuka had never received a formal education. Tesla credited his eidetic memory and creative abilities to his mother's genetics and influence.[17][18]

Tesla was the fourth of five children. He had three sisters, Milka, Angelina, and Marica, and an older brother named Dane, who was killed in a horse-riding accident when Tesla was aged six or seven.[19] In 1861, Tesla attended primary school in Smiljan where he studied German, arithmetic, and religion. In 1862, the Tesla family moved to the nearby town of Gospić, where Tesla's father worked as parish priest. Nikola completed primary school, followed by middle school. In 1870, Tesla moved to Karlovac[20] to attend high school at the Higher Real Gymnasium where the classes were held in German, as it was usual throughout schools within the Austro-Hungarian Military Frontier.[21][22] Later in his patent applications, before he obtained American citizenship, Tesla would identify himself as 'of Smiljan, Lika, border country of Austria-Hungary'.[23]

Tesla later wrote that he became interested in demonstrations of electricity by his physics professor.[a] Tesla noted that these demonstrations of this "mysterious phenomena" made him want "to know more of this wonderful force".[26] Tesla was able to perform integral calculus in his head, which prompted his teachers to believe that he was cheating.[27] He finished a four-year term in three years, graduating in 1873.[28]

After graduating Tesla returned to Smiljan but soon contracted cholera, was bedridden for nine months and was near death multiple times. In a moment of despair, Tesla's father (who had originally wanted him to enter the priesthood),[29] promised to send him to the best engineering school if he recovered from the illness.[30] Tesla later said that he had read Mark Twain's earlier works while recovering from his illness.[31][32]

The next year Tesla evaded conscription into the Austro-Hungarian Army in Smiljan[33] by running away southeast of Lika to Tomingaj, near Gračac. There he explored the mountains wearing hunter's garb. Tesla said that this contact with nature made him stronger, both physically and mentally. He enrolled at the Imperial-Royal Technical College in Graz in 1875 on a Military Frontier scholarship. Tesla passed nine exams (nearly twice as many as required[34]) and received a letter of commendation from the dean of the technical faculty to his father, which stated, "Your son is a star of first rank."[34] At Graz, Tesla noted his fascination with the detailed lectures on electricity presented by Professor Jakob Pöschl and described how he made suggestions on improving the design of an electric motor the professor was demonstrating.[31][better source needed][35] But by his third year he was failing in school and never graduated, leaving Graz in December 1878. One biographer suggests Tesla was not studying and may have been expelled for gambling and womanizing.[36]

Tesla's family did not hear from him after he left school.[37] There was a rumor among his classmates that he had drowned in the nearby river Mur but in January one of them ran into Tesla in the town of Maribor and reported that encounter to Tesla's family.[38] It turned out Tesla had been working there as a draftsman for 60 florins per month.[36] In March 1879, Milutin finally located his son and tried to convince him to return home and take up his education in Prague.[38] Tesla returned to Gospić later that month when he was deported for not having a residence permit.[38] Tesla's father died the next month, on 17 April 1879, at the age of 60 after an unspecified illness.[38] During the rest of the year Tesla taught a large class of students in his old school in Gospić.

In January 1880, two of Tesla's uncles put together enough money to help him leave Gospić for Prague, where he was to study. He arrived too late to enroll at Charles-Ferdinand University; he had never studied Greek, a required subject; and he was illiterate in Czech, another required subject. Tesla did, however, attend lectures in philosophy at the university as an auditor but he did not receive grades for the courses.[39][40]

Working at Budapest Telephone Exchange

Tesla moved to Budapest, Hungary, in 1881 to work under Tivadar Puskás at a telegraph company, the Budapest Telephone Exchange. Upon arrival, Tesla realized that the company, then under construction, was not functional, so he worked as a draftsman in the Central Telegraph Office instead. Within a few months, the Budapest Telephone Exchange became functional, and Tesla was allocated the chief electrician position. During his employment, Tesla made many improvements to the Central Station equipment and claimed to have perfected a telephone repeater or amplifier, which was never patented nor publicly described.[31][better source needed]

Working at Edison

In 1882, Tivadar Puskás got Tesla another job in Paris with the Continental Edison Company.[41] Tesla began working in what was then a brand new industry, installing indoor incandescent lighting citywide in large scale electric power utility. The company had several subdivisions and Tesla worked at the Société Electrique Edison, the division in the Ivry-sur-Seine suburb of Paris in charge of installing the lighting system. There he gained a great deal of practical experience in electrical engineering. Management took notice of his advanced knowledge in engineering and physics and soon had him designing and building improved versions of generating dynamos and motors.[42] They also sent him on to troubleshoot engineering problems at other Edison utilities being built around France and in Germany.

Moving to the United States

In 1884, Edison manager Charles Batchelor, who had been overseeing the Paris installation, was brought back to the United States to manage the Edison Machine Works, a manufacturing division situated in New York City, and asked that Tesla be brought to the United States as well.[44] In June 1884, Tesla emigrated[45] and began working almost immediately at the Machine Works on Manhattan's Lower East Side, an overcrowded shop with a workforce of several hundred machinists, laborers, managing staff, and 20 "field engineers" struggling with the task of building the large electric utility in that city.[46] As in Paris, Tesla was working on troubleshooting installations and improving generators.[47] Historian W. Bernard Carlson notes Tesla may have met company founder Thomas Edison only a couple of times.[46] One of those times was noted in Tesla's autobiography where, after staying up all night repairing the damaged dynamos on the ocean liner SS Oregon, he ran into Batchelor and Edison, who made a quip about their "Parisian" being out all night. After Tesla told them he had been up all night fixing the Oregon, Edison commented to Batchelor that "this is a damned good man".[43] One of the projects given to Tesla was to develop an arc lamp-based street lighting system.[48][49] Arc lighting was the most popular type of street lighting but it required high voltages and was incompatible with the Edison low-voltage incandescent system, causing the company to lose contracts in some cities. Tesla's designs were never put into production, possibly because of technical improvements in incandescent street lighting or because of an installation deal that Edison made with an arc lighting company.[50]

Tesla had been working at the Machine Works for a total of six months when he quit.[46] What event precipitated his leaving is unclear. It may have been over a bonus he did not receive, either for redesigning generators or for the arc lighting system that was shelved.[48] Tesla had previous run-ins with the Edison company over unpaid bonuses he believed he had earned.[51][52] In his autobiography, Tesla stated the manager of the Edison Machine Works offered a $50,000 bonus to design "twenty-four different types of standard machines" "but it turned out to be a practical joke".[53][better source needed] Later versions of this story have Thomas Edison himself offering and then reneging on the deal, quipping "Tesla, you don't understand our American humor".[54][55] The size of the bonus in either story has been noted as odd since Machine Works manager Batchelor was stingy with pay[b] and the company did not have that amount of cash (equal to $1,695,556 today) on hand.[57][58] Tesla's diary contains just one comment on what happened at the end of his employment, a note he scrawled across the two pages covering 7 December 1884, to 4 January 1885, saying "Good By to the Edison Machine Works".[49][59]

Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing

Soon after leaving the Edison company, Tesla was working on patenting an arc lighting system,[60] possibly the same one he had developed at Edison.[46] In March 1885, he met with patent attorney Lemuel W. Serrell, the same attorney used by Edison, to obtain help with submitting the patents.[60] Serrell introduced Tesla to two businessmen, Robert Lane and Benjamin Vail, who agreed to finance an arc lighting manufacturing and utility company in Tesla's name, the Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing Company.[61] Tesla worked for the rest of the year obtaining the patents that included an improved DC generator, the first patents issued to Tesla in the US, and building and installing the system in Rahway, New Jersey.[62] Tesla's new system gained notice in the technical press, which commented on its advanced features.

The investors showed little interest in Tesla's ideas for new types of alternating current motors and electrical transmission equipment. After the utility was up and running in 1886, they decided that the manufacturing side of the business was too competitive and opted to simply run an electric utility.[63] They formed a new utility company, abandoning Tesla's company and leaving the inventor penniless.[63] Tesla even lost control of the patents he had generated, since he had assigned them to the company in exchange for stock.[63] He had to work at various electrical repair jobs and as a ditch digger for $2 per day. Later in life Tesla recounted that part of 1886 as a time of hardship, writing "My high education in various branches of science, mechanics and literature seemed to me like a mockery".[63][c]

AC and the induction motor

In late 1886, Tesla met Alfred S. Brown, a Western Union superintendent, and New York attorney Charles Fletcher Peck.[65] The two men were experienced in setting up companies and promoting inventions and patents for financial gain.[66] Based on Tesla's new ideas for electrical equipment, including a thermo-magnetic motor idea,[67] they agreed to back the inventor financially and handle his patents. Together they formed the Tesla Electric Company in April 1887, with an agreement that profits from generated patents would go 1⁄3 to Tesla, 1⁄3 to Peck and Brown, and 1⁄3 to fund development.[66] They set up a laboratory for Tesla at 89 Liberty Street in Manhattan, where he worked on improving and developing new types of electric motors, generators, and other devices.

In 1887, Tesla developed an induction motor that ran on alternating current (AC), a power system format that was rapidly expanding in Europe and the United States because of its advantages in long-distance, high-voltage transmission. The motor used polyphase current, which generated a rotating magnetic field to turn the motor (a principle that Tesla claimed to have conceived in 1882).[68][69][70] This innovative electric motor, patented in May 1888, was a simple self-starting design that did not need a commutator, thus avoiding sparking and the high maintenance of constantly servicing and replacing mechanical brushes.[71][72]

Along with getting the motor patented, Peck and Brown arranged to get the motor publicized, starting with independent testing to verify it was a functional improvement, followed by press releases sent to technical publications for articles to run concurrently with the issue of the patent.[73] Physicist William Arnold Anthony (who tested the motor) and Electrical World magazine editor Thomas Commerford Martin arranged for Tesla to demonstrate his AC motor on 16 May 1888 at the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.[73][74] Engineers working for the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company reported to George Westinghouse that Tesla had a viable AC motor and related power system—something Westinghouse needed for the alternating current system he was already marketing. Westinghouse looked into getting a patent on a similar commutator-less, rotating magnetic field-based induction motor developed in 1885 and presented in a paper in March 1888 by Italian physicist Galileo Ferraris, but decided that Tesla's patent would probably control the market.[75][76]

In July 1888, Brown and Peck negotiated a licensing deal with George Westinghouse for Tesla's polyphase induction motor and transformer designs for $60,000 in cash and stock and a royalty of $2.50 per AC horsepower produced by each motor. Westinghouse also hired Tesla for one year for the large fee of $2,000 ($67,800 in today's dollars[77]) per month to be a consultant at the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company's Pittsburgh labs.[78]

During that year, Tesla worked in Pittsburgh, helping to create an alternating current system to power the city's streetcars. He found it a frustrating period because of conflicts with the other Westinghouse engineers over how best to implement AC power. Between them, they settled on a 60-cycle AC system that Tesla proposed (to match the working frequency of Tesla's motor), but they soon found that it would not work for streetcars, since Tesla's induction motor could run only at a constant speed. They ended up using a DC traction motor instead.[79][80]

Market turmoil

Tesla's demonstration of his induction motor and Westinghouse's subsequent licensing of the patent, both in 1888, came at the time of extreme competition between electric companies.[81][82] The three big firms, Westinghouse, Edison, and Thomson-Houston Electric Company, were trying to grow in a capital-intensive business while financially undercutting each other. There was even a "war of currents" propaganda campaign going on, with Edison Electric claiming their direct current system was better and safer than the Westinghouse alternating current system and Thomson-Houston sometimes siding with Edison.[83][84] Competing in this market meant Westinghouse would not have the cash or engineering resources to develop Tesla's motor and the related polyphase system right away.[85]

Two years after signing the Tesla contract, Westinghouse Electric was in trouble. The near collapse of Barings Bank in London triggered the financial panic of 1890, causing investors to call in their loans to Westinghouse Electric.[86] The sudden cash shortage forced the company to refinance its debts. The new lenders demanded that Westinghouse cut back on what looked like excessive spending on acquisition of other companies, research, and patents, including the per motor royalty in the Tesla contract.[87][88] At that point, the Tesla induction motor had been unsuccessful and was stuck in development.[85][86] Westinghouse was paying a $15,000-a-year guaranteed royalty[89] even though operating examples of the motor were rare and polyphase power systems needed to run it was even rarer.[71][86] In early 1891, George Westinghouse explained his financial difficulties to Tesla in stark terms, saying that, if he did not meet the demands of his lenders, he would no longer be in control of Westinghouse Electric and Tesla would have to "deal with the bankers" to try to collect future royalties.[90] The advantages of having Westinghouse continue to champion the motor probably seemed obvious to Tesla and he agreed to release the company from the royalty payment clause in the contract.[90][91] Six years later Westinghouse purchased Tesla's patent for a lump sum payment of $216,000 as part of a patent-sharing agreement signed with General Electric (a company created from the 1892 merger of Edison and Thomson-Houston).[92][93][94]

New York laboratories

The money Tesla made from licensing his AC patents made him independently wealthy and gave him the time and funds to pursue his own interests.[95] In 1889, Tesla moved out of the Liberty Street shop Peck and Brown had rented and for the next dozen years worked out of a series of workshop/laboratory spaces in Manhattan. These included a lab at 175 Grand Street (1889–1892), the fourth floor of 33–35 South Fifth Avenue (1892–1895), and sixth and seventh floors of 46 & 48 East Houston Street (1895–1902).[96][97] Tesla and his hired staff conducted some of his most significant work in these workshops.

Tesla coil

In the summer of 1889, Tesla traveled to the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris and learned of Heinrich Hertz's 1886–1888 experiments that proved the existence of electromagnetic radiation, including radio waves.[98] In repeating and then expanding on these experiments Tesla tried powering a Ruhmkorff coil with a high speed alternator he had been developing as part of an improved arc lighting system but found that the high-frequency current overheated the iron core and melted the insulation between the primary and secondary windings in the coil. To fix this problem Tesla came up with his "oscillating transformer", with an air gap instead of insulating material between the primary and secondary windings and an iron core that could be moved to different positions in or out of the coil.[99] Later called the Tesla coil, it would be used to produce high-voltage, low-current, high frequency alternating-current electricity.[100] He would use this resonant transformer circuit in his later wireless power work.[101][102]

Citizenship

On 30 July 1891, aged 35, Tesla became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[103][104] In the same year, he patented his Tesla coil.[105]

Wireless lighting

After 1890, Tesla experimented with transmitting power by inductive and capacitive coupling using high AC voltages generated with his Tesla coil.[106] He attempted to develop a wireless lighting system based on near-field inductive and capacitive coupling and conducted a series of public demonstrations where he lit Geissler tubes and even incandescent light bulbs from across a stage.[107] He spent most of the decade working on variations of this new form of lighting with the help of various investors but none of the ventures succeeded in making a commercial product out of his findings.[108]

In 1893 at St. Louis, Missouri, the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the National Electric Light Association, Tesla told onlookers that he was sure a system like his could eventually conduct "intelligible signals or perhaps even power to any distance without the use of wires" by conducting it through the Earth.[109][110]

Tesla served as a vice-president of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers from 1892 to 1894, the forerunner of the modern-day IEEE (along with the Institute of Radio Engineers).[111]

Polyphase system and the Columbian Exposition

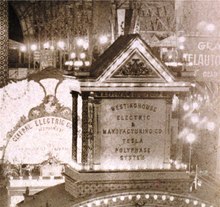

By the beginning of 1893, Westinghouse engineer Charles F. Scott and then Benjamin G. Lamme had made progress on an efficient version of Tesla's induction motor. Lamme found a way to make the polyphase system it would need compatible with older single-phase AC and DC systems by developing a rotary converter.[112] Westinghouse Electric now had a way to provide electricity to all potential customers and started branding their polyphase AC system as the "Tesla Polyphase System". They believed that Tesla's patents gave them patent priority over other polyphase AC systems.[113]

Westinghouse Electric asked Tesla to participate in the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago where the company had a large space in the "Electricity Building" devoted to electrical exhibits. Westinghouse Electric won the bid to light the Exposition with alternating current and it was a key event in the history of AC power, as the company demonstrated to the American public the safety, reliability, and efficiency of an alternating current system that was polyphase and could also supply the other AC and DC exhibits at the fair.[114][115][116]

A special exhibit space was set up to display various forms and models of Tesla's induction motor. The rotating magnetic field that drove them was explained through a series of demonstrations including an Egg of Columbus that used the two-phase coil found in an induction motor to spin a copper egg making it stand on end.[117]

Tesla visited the fair for a week during its six-month run to attend the International Electrical Congress and put on a series of demonstrations at the Westinghouse exhibit.[118][119] A specially darkened room had been set up where Tesla showed his wireless lighting system, using a demonstration he had previously performed throughout America and Europe;[120] these included using high-voltage, high-frequency alternating current to light wireless gas-discharge lamps.[121]

An observer noted:

Within the room were suspended two hard-rubber plates covered with tin foil. These were about fifteen feet apart and served as terminals of the wires leading from the transformers. When the current was turned on, the lamps or tubes, which had no wires connected to them, but lay on a table between the suspended plates, or which might be held in the hand in almost any part of the room, were made luminous. These were the same experiments and the same apparatus shown by Tesla in London about two years previous, "where they produced so much wonder and astonishment".[122]

Steam-powered oscillating generator

During his presentation at the International Electrical Congress in the Columbian Exposition Agriculture Hall, Tesla introduced his steam powered reciprocating electricity generator that he patented that year, something he thought was a better way to generate alternating current.[123] Steam was forced into the oscillator and rushed out through a series of ports, pushing a piston up and down that was attached to an armature. The magnetic armature vibrated up and down at high speed, producing an alternating magnetic field. This induced alternating electric current in the wire coils located adjacent. It did away with the complicated parts of a steam engine/generator, but never caught on as a feasible engineering solution to generate electricity.[124][125]

Consulting on Niagara

In 1893, Edward Dean Adams, who headed the Niagara Falls Cataract Construction Company, sought Tesla's opinion on what system would be best to transmit power generated at the falls. Over several years, there had been a series of proposals and open competitions on how best to do it. Among the systems proposed by several US and European companies were two-phase and three-phase AC, high-voltage DC, and compressed air. Adams asked Tesla for information about the current state of all the competing systems. Tesla advised Adams that a two-phased system would be the most reliable and that there was a Westinghouse system to light incandescent bulbs using two-phase alternating current. The company awarded a contract to Westinghouse Electric for building a two-phase AC generating system at the Niagara Falls, based on Tesla's advice and Westinghouse's demonstration at the Columbian Exposition. At the same time, a further contract was awarded to General Electric to build the AC distribution system.[126]

The Nikola Tesla Company

In 1895, Edward Dean Adams, impressed with what he saw when he toured Tesla's lab, agreed to help found the Nikola Tesla Company, set up to fund, develop, and market a variety of previous Tesla patents and inventions as well as new ones. Alfred Brown signed on, bringing along patents developed under Peck and Brown. The board was filled out with William Birch Rankine and Charles F. Coaney.[127] It found few investors since the mid-1890s were a tough time financially, and the wireless lighting and oscillators patents it was set up to market never panned out. The company handled Tesla's patents for decades to come.

Lab fire

In the early morning hours of 13 March 1895, the South Fifth Avenue building that housed Tesla's lab caught fire. It started in the basement of the building and was so intense Tesla's 4th-floor lab burned and collapsed into the second floor. The fire not only set back Tesla's ongoing projects, but it also destroyed a collection of early notes and research material, models, and demonstration pieces, including many that had been exhibited at the 1893 Worlds Colombian Exposition. Tesla told The New York Times "I am in too much grief to talk. What can I say?".[128] After the fire Tesla moved to 46 & 48 East Houston Street and rebuilt his lab on the 6th and 7th floors.

X-ray experimentation

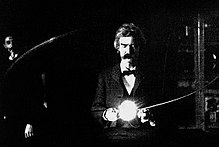

Starting in 1894, Tesla began investigating what he referred to as radiant energy of "invisible" kinds after he had noticed damaged film in his laboratory in previous experiments[129] (later identified as "Roentgen rays" or "X-rays"). His early experiments were with Crookes tubes, a cold cathode electrical discharge tube. Tesla may have inadvertently captured an X-ray image—predating, by a few weeks, Wilhelm Röntgen's December 1895 announcement of the discovery of X-rays—when he tried to photograph Mark Twain illuminated by a Geissler tube, an earlier type of gas discharge tube. The only thing captured in the image was the metal locking screw on the camera lens.[130]

In March 1896, after hearing of Röntgen's discovery of X-ray and X-ray imaging (radiography),[131] Tesla proceeded to do his own experiments in X-ray imaging, developing a high-energy single-terminal vacuum tube of his own design that had no target electrode and that worked from the output of the Tesla coil (the modern term for the phenomenon produced by this device is bremsstrahlung or braking radiation). In his research, Tesla devised several experimental setups to produce X-rays. Tesla held that, with his circuits, the "instrument will ... enable one to generate Roentgen rays of much greater power than obtainable with ordinary apparatus".[132]

Tesla noted the hazards of working with his circuit and single-node X-ray-producing devices. In his many notes on the early investigation of this phenomenon, he attributed the skin damage to various causes. He believed early on that damage to the skin was not caused by the Roentgen rays, but by the ozone generated in contact with the skin, and to a lesser extent, by nitrous acid. Tesla incorrectly believed that X-rays were longitudinal waves, such as those produced in waves in plasmas. These plasma waves can occur in force-free magnetic fields.[133][134]

On 11 July 1934, the New York Herald Tribune published an article on Tesla, in which he recalled an event that occasionally took place while experimenting with his single-electrode vacuum tubes. A minute particle would break off the cathode, pass out of the tube, and physically strike him:[135]

Tesla said he could feel a sharp stinging pain where it entered his body, and again at the place where it passed out. In comparing these particles with the bits of metal projected by his "electric gun", Tesla said, "The particles in the beam of force ... will travel much faster than such particles ... and they will travel in concentrations".

Radio remote control

In 1898, Tesla demonstrated a boat that used a coherer-based radio control—which he dubbed "telautomaton"—to the public during an electrical exhibition at Madison Square Garden.[137] Tesla tried to sell his idea to the US military as a type of radio-controlled torpedo, but they showed little interest.[138] Remote radio control remained a novelty until World War I and afterward, when a number of countries used it in military programs.[139] Tesla took the opportunity to further demonstrate "Teleautomatics" in an address to a meeting of the Commercial Club in Chicago, while he was traveling to Colorado Springs, on 13 May 1899.

Wireless power

From the 1890s through 1906, Tesla spent a great deal of his time and fortune on a series of projects trying to develop the transmission of electrical power without wires. It was an expansion of his idea of using coils to transmit power that he had been demonstrating in wireless lighting. He saw this as not only a way to transmit large amounts of power around the world but also, as he had pointed out in his earlier lectures, a way to transmit worldwide communications.

At the time Tesla was formulating his ideas, there was no feasible way to wirelessly transmit communication signals over long distances, let alone large amounts of power. Tesla had studied radio waves early on, and came to the conclusion that part of the existing study on them, by Hertz, was incorrect.[140][141][d] Also, this new form of radiation was widely considered at the time to be a short-distance phenomenon that seemed to die out in less than a mile.[143] Tesla noted that, even if theories on radio waves were true, they were totally worthless for his intended purposes since this form of "invisible light" would diminish over a distance just like any other radiation and would travel in straight lines right out into space, becoming "hopelessly lost".[144]

By the mid-1890s, Tesla was working on the idea that he might be able to conduct electricity long distance through the Earth or the atmosphere, and began working on experiments to test this idea including setting up a large resonance transformer magnifying transmitter in his East Houston Street lab.[145][146][147] Seeming to borrow from a common idea at the time that the Earth's atmosphere was conductive,[148][149] he proposed a system composed of balloons suspending, transmitting, and receiving, electrodes in the air above 30,000 feet (9,100 m) in altitude, where he thought the lower pressure would allow him to send high voltages (millions of volts) long distances.

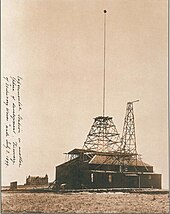

Colorado Springs

To further study the conductive nature of low-pressure air, Tesla set up an experimental station at high altitude in Colorado Springs during 1899.[150][151][152][153] There he could safely operate much larger coils than in the cramped confines of his New York lab, and an associate had made an arrangement for the El Paso Electric Light Company to supply alternating current free of charge.[153] To fund his experiments, he convinced John Jacob Astor IV to invest $100,000 ($3,662,400 in today's dollars[77]) to become a majority shareholder in the Nikola Tesla Company. Astor thought he was primarily investing in the new wireless lighting system. Instead, Tesla used the money to fund his Colorado Springs experiments.[154] Upon his arrival, he told reporters that he planned to conduct wireless telegraphy experiments, transmitting signals from Pikes Peak to Paris.[155]

There, he conducted experiments with a large coil operating in the megavolts range, producing artificial lightning (and thunder) consisting of millions of volts and discharges of up to 135 feet (41 m) in length,[157] and, at one point, inadvertently burned out the generator in El Paso, causing a power outage.[158] The observations he made of the electronic noise of lightning strikes led him to (incorrectly) conclude[159][160] that he could use the entire globe of the Earth to conduct electrical energy.

During his time at his laboratory, Tesla observed unusual signals from his receiver which he speculated to be communications from another planet. He mentioned them in a letter to a reporter in December 1899[161] and to the Red Cross Society in December 1900.[162][163] Reporters treated it as a sensational story and jumped to the conclusion Tesla was hearing signals from Mars.[162] He expanded on the signals he heard in a 9 February 1901 Collier's Weekly article entitled "Talking With Planets", where he said it had not been immediately apparent to him that he was hearing "intelligently controlled signals" and that the signals could have come from Mars, Venus, or other planets.[163] It has been hypothesized that he may have intercepted Guglielmo Marconi's European experiments in July 1899—Marconi may have transmitted the letter S (dot/dot/dot) in a naval demonstration, the same three impulses that Tesla hinted at hearing in Colorado[163]—or signals from another experimenter in wireless transmission.[164][unreliable source?]

Tesla had an agreement with the editor of The Century Magazine to produce an article on his findings. The magazine sent a photographer to Colorado to photograph the work being done there. The article, titled "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy", appeared in the June 1900 edition of the magazine. He explained the superiority of the wireless system he envisioned but the article was more of a lengthy philosophical treatise than an understandable scientific description of his work,[165] illustrated with what were to become iconic images of Tesla and his Colorado Springs experiments.

Wardenclyffe

Tesla made the rounds in New York trying to find investors for what he thought would be a viable system of wireless transmission, wining and dining them at the Waldorf-Astoria's Palm Garden (the hotel where he was living at the time), The Players Club, and Delmonico's.[166] In March 1901, he obtained $150,000 ($5,493,600 in today's dollars[77]) from J. P. Morgan in return for a 51% share of any generated wireless patents, and began planning the Wardenclyffe Tower facility to be built in Shoreham, New York, 100 miles (161 km) east of the city on the North Shore of Long Island.[167]

By July 1901, Tesla had expanded his plans to build a more powerful transmitter to leap ahead of Marconi's radio-based system, which Tesla thought was a copy of his own.[162] He approached Morgan to ask for more money to build the larger system, but Morgan refused to supply any further funds.[164][unreliable source?] In December 1901, Marconi successfully transmitted the letter S from England to Newfoundland, defeating Tesla in the race to be first to complete such a transmission. A month after Marconi's success, Tesla tried to get Morgan to back an even larger plan to transmit messages and power by controlling "vibrations throughout the globe".[162] Over the next five years, Tesla wrote more than 50 letters to Morgan, pleading for and demanding additional funding to complete the construction of Wardenclyffe. Tesla continued the project for another nine months into 1902. The tower was erected to its full height of 187 feet (57 m).[164][unreliable source?] In June 1902, Tesla moved his lab operations from Houston Street to Wardenclyffe.[167]

Investors on Wall Street were putting their money into Marconi's system, and some in the press began turning against Tesla's project, claiming it was a hoax.[168] The project came to a halt in 1905, and in 1906, the financial problems and other events may have led to what Tesla biographer Marc J. Seifer suspects was a nervous breakdown on Tesla's part.[169] Tesla mortgaged the Wardenclyffe property to cover his debts at the Waldorf-Astoria, which eventually amounted to $20,000 ($608,400 in today's dollars[77]).[170] He lost the property in foreclosure in 1915, and in 1917 the Tower was demolished by the new owner to make the land a more viable real estate asset.

Later years

After Wardenclyffe closed, Tesla continued to write to Morgan; after "the great man" died, Tesla wrote to Morgan's son Jack, trying to get further funding for the project. In 1906, Tesla opened offices at 165 Broadway in Manhattan, trying to raise further funds by developing and marketing his patents. He went on to have offices at the Metropolitan Life Tower from 1910 to 1914; rented for a few months at the Woolworth Building, moving out because he could not afford the rent; and then to office space at 8 West 40th Street from 1915 to 1925. After moving to 8 West 40th Street, he was effectively bankrupt. Most of his patents had run out and he was having trouble with the new inventions he was trying to develop.[171]

Bladeless turbine

On his 50th birthday, in 1906, Tesla demonstrated a 200 horsepower (150 kilowatts) 16,000 rpm bladeless turbine. During 1910–1911, at the Waterside Power Station in New York, several of his bladeless turbine engines were tested at 100–5,000 hp.[172] Tesla worked with several companies including from 1919 to 1922 in Milwaukee, for Allis-Chalmers.[173][174] He spent most of his time trying to perfect the Tesla turbine with Hans Dahlstrand, the head engineer at the company, but engineering difficulties meant it was never made into a practical device.[175][page needed] Tesla did license the idea to a precision instrument company and it found use in the form of luxury car speedometers and other instruments.[176]

Wireless lawsuits

When World War I broke out, the British cut the transatlantic telegraph cable linking the US to Germany in order to control the flow of information between the two countries. They also tried to shut off German wireless communication to and from the US by having the US Marconi Company sue the German radio company Telefunken for patent infringement.[177] Telefunken brought in the physicists Jonathan Zenneck and Karl Ferdinand Braun for their defense, and hired Tesla as a witness for two years for $1,000 a month. The case stalled and then went moot when the US entered the war against Germany in 1917.[177][178]

In 1915, Tesla attempted to sue the Marconi Company for infringement of his wireless tuning patents. Marconi's initial radio patent had been awarded in the US in 1897, but his 1900 patent submission covering improvements to radio transmission had been rejected several times, before it was finally approved in 1904, on the grounds that it infringed on other existing patents including two 1897 Tesla wireless power tuning patents.[141][179][180] Tesla's 1915 case went nowhere,[181] but in a related case, where the Marconi Company tried to sue the US government over WWI patent infringements, a Supreme Court of the United States 1943 decision restored the prior patents of Oliver Lodge, John Stone, and Tesla.[182] The court declared that their decision had no bearing on Marconi's claim as the first to achieve radio transmission, just that since Marconi's claim to certain patented improvements were questionable, the company could not claim infringement on those same patents.[141][183]

Nobel Prize rumors

On 6 November 1915, a Reuters news agency report from London had the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla; however, on 15 November, a Reuters story from Stockholm stated the prize that year was being awarded to William Henry Bragg and Lawrence Bragg "for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays".[184][185][186] There were unsubstantiated rumors at the time that either Tesla or Edison had refused the prize.[184] The Nobel Foundation said, "Any rumor that a person has not been given a Nobel Prize because he has made known his intention to refuse the reward is ridiculous"; a recipient could decline a Nobel Prize only after he is announced a winner.[184]

There have been subsequent claims by Tesla biographers that Edison and Tesla were the original recipients and that neither was given the award because of their animosity toward each other; that each sought to minimize the other's achievements and right to win the award; that both refused ever to accept the award if the other received it first; that both rejected any possibility of sharing it; and even that a wealthy Edison refused it to keep Tesla from getting the $20,000 prize money.[18][184]

In the years after these rumors, neither Tesla nor Edison won a Nobel prize (although Edison received one of 38 possible bids in 1915 and Tesla received one of 38 possible bids in 1937).[187]

Other awards, patents and ideas

Tesla won numerous medals and awards over this time. They include:

- Grand Officer of the Order of St. Sava (Serbia, 1892)

- Elliott Cresson Medal (Franklin Institute, US, 1894)[188]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I (Montenegro, 1895)[189]

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (US, 1896)[190]

- AIEE Edison Medal (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, US, 1916)[191]

- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Sava (Yugoslavia, 1926)[192]

- Cross of the Order of the Yugoslav Crown (Yugoslavia, 1931)

- John Scott Medal (Franklin Institute & Philadelphia City Council, US, 1934)[188]

- Order of the White Eagle (Yugoslavia, 1936)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion (Czechoslovakia, 1937)[193]

- Medal of the University of Paris (Paris, France, 1937)

- The Medal of the University St. Clement of Ochrida (Sofia, Bulgaria, 1939)

Tesla attempted to market several devices based on the production of ozone. These included his 1900 Tesla Ozone Company selling an 1896 patented device based on his Tesla coil, used to bubble ozone through different types of oils to make a therapeutic gel.[194] He also tried to develop a variation of this a few years later as a room sanitizer for hospitals.[195]

Tesla theorized that the application of electricity to the brain enhanced intelligence. In 1912, he crafted "a plan to make dull students bright by saturating them unconsciously with electricity," wiring the walls of a schoolroom and, "saturating [the schoolroom] with infinitesimal electric waves vibrating at high frequency. The whole room will thus, Mr. Tesla claims, be converted into a health-giving and stimulating electromagnetic field or 'bath.'"[196] The plan was, at least provisionally, approved by then superintendent of New York City schools, William H. Maxwell.[196]

Before World War I, Tesla sought overseas investors. After the war started, Tesla lost the funding he was receiving from his patents in European countries.

In the August 1917 edition of the magazine Electrical Experimenter, Tesla postulated that electricity could be used to locate submarines via using the reflection of an "electric ray" of "tremendous frequency," with the signal being viewed on a fluorescent screen (a system that has been noted to have a superficial resemblance to modern radar).[197] Tesla was incorrect in his assumption that high-frequency radio waves would penetrate water.[198] Émile Girardeau, who helped develop France's first radar system in the 1930s, noted in 1953 that Tesla's general speculation that a very strong high-frequency signal would be needed was correct. Girardeau said, "(Tesla) was prophesying or dreaming, since he had at his disposal no means of carrying them out, but one must add that if he was dreaming, at least he was dreaming correctly".[199]

In 1928, Tesla received patent, U.S. patent 1,655,114, for a biplane design capable of vertical take-off and landing (VTOL), which "gradually tilted through manipulation of the elevator devices" in flight until it was flying like a conventional plane.[200] This impractical design was something Tesla thought would sell for less than $1,000.[201][202]

Tesla had a further office at 350 Madison Ave[203] but by 1928 he no longer had a laboratory or funding.[202]

Living circumstances

Tesla lived at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City from 1900 and ran up a large bill.[204] He moved to the St. Regis Hotel in 1922 and followed a pattern from then on of moving to a different hotel every few years and leaving unpaid bills behind.[205][206]

Tesla walked to the park every day to feed the pigeons. He began feeding them at the window of his hotel room and nursed injured birds back to health.[206][207][208] He said that he had been visited by a certain injured white pigeon daily. He spent over $2,000 (equivalent to $36,410 in 2023) to care for the bird, including a device he built to support her comfortably while her broken wing and leg healed.[209] Tesla stated:

I have been feeding pigeons, thousands of them for years. But there was one, a beautiful bird, pure white with light grey tips on its wings; that one was different. It was a female. I had only to wish and call her and she would come flying to me. I loved that pigeon as a man loves a woman, and she loved me. As long as I had her, there was a purpose to my life.[210]

Tesla's unpaid bills, as well as complaints about the mess made by pigeons, led to his eviction from St. Regis in 1923. He was also forced to leave the Hotel Pennsylvania in 1930 and the Hotel Governor Clinton in 1934.[206] At one point he also took rooms at the Hotel Marguery.[211]

Tesla moved to the Hotel New Yorker in 1934. At this time Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company began paying him $125 (equivalent to $2,850 in 2023) per month in addition to paying his rent. Accounts of how this came about vary. Several sources claim that Westinghouse was concerned, or possibly warned, about potential bad publicity arising from the impoverished conditions in which their former star inventor was living.[212][213][214][215] The payment has been described as being couched as a "consulting fee" to get around Tesla's aversion to accepting charity. Tesla biographer Marc Seifer described the Westinghouse payments as a type of "unspecified settlement".[214]

Birthday press conferences

In 1931, a young journalist whom Tesla befriended, Kenneth M. Swezey, organized a celebration for the inventor's 75th birthday.[216] Tesla received congratulations from figures in science and engineering such as Albert Einstein,[217] and he was also featured on the cover of Time magazine.[218] The cover caption "All the world's his power house" noted his contribution to electrical power generation. The party went so well that Tesla made it an annual event, an occasion where he would put out a large spread of food and drink—featuring dishes of his own creation. He invited the press in order to see his inventions and hear stories about his past exploits, views on current events, and sometimes baffling claims.[219][220]

At the 1932 party, Tesla claimed he had invented a motor that would run on cosmic rays.[220] In 1933, at age 77, Tesla told reporters at the event that, after 35 years of work, he was on the verge of producing proof of a new form of energy. He claimed it was a theory of energy that was "violently opposed" to Einsteinian physics and could be tapped with an apparatus that would be cheap to run and last 500 years. He also told reporters he was working on a way to transmit individualized private radio wavelengths, working on breakthroughs in metallurgy, and developing a way to photograph the retina to record thought.[221]

At the 1934 occasion, Tesla told reporters he had designed a superweapon he claimed would end all war.[222][223] He called it "teleforce", but was usually referred to as his death ray.[224] In 1940, the New York Times gave a range for the ray of 250 miles (400 km), with an expected development cost of US$2 million (equivalent to $43.5 million in 2023).[225] Tesla described it as a defensive weapon that would be put up along the border of a country and be used against attacking ground-based infantry or aircraft. Tesla never revealed detailed plans of how the weapon worked during his lifetime but, in 1984, they surfaced at the Nikola Tesla Museum archive in Belgrade.[226] The treatise, The New Art of Projecting Concentrated Non-dispersive Energy through the Natural Media, described an open-ended vacuum tube with a gas jet seal that allows particles to exit, a method of charging slugs of tungsten or mercury to millions of volts, and directing them in streams (through electrostatic repulsion).[220][227] Tesla tried to attract interest of the US War Department,[228] United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia in the device.[229]

In 1935, at his 79th birthday party, Tesla covered many topics. He claimed to have discovered the cosmic ray in 1896 and invented a way to produce direct current by induction, and made many claims about his mechanical oscillator.[230] Describing the device (which he expected would earn him $100 million within two years) he told reporters that a version of his oscillator had caused an earthquake in his 46 East Houston Street lab and neighboring streets in Lower Manhattan in 1898.[230] He went on to tell reporters his oscillator could destroy the Empire State Building with 5 pounds (2.3 kg) of air pressure.[231] He also proposed using his oscillators to transmit vibrations into the ground. He claimed it would work over any distance and could be used for communication or locating underground mineral deposits, a technique he called "telegeodynamics".[135]

In 1937, at his Grand Ballroom of Hotel New Yorker event, Tesla received the Order of the White Lion from the Czechoslovak ambassador and a medal from the Yugoslav ambassador. On questions concerning the death ray, Tesla stated: "But it is not an experiment ... I have built, demonstrated and used it. Only a little time will pass before I can give it to the world."[220]

Death

In the fall of 1937 at the age of 81, after midnight one night, Tesla left the Hotel New Yorker to make his regular commute to the cathedral and library to feed the pigeons. While crossing a street a couple of blocks from the hotel, Tesla was struck by a moving taxicab and was thrown to the ground. His back was severely wrenched and three of his ribs were broken in the accident. The full extent of his injuries was never known; Tesla refused to consult a doctor, an almost lifelong custom, and never fully recovered.[232][233]

On 7 January 1943, at the age of 86, Tesla died alone in Room 3327 of the Hotel New Yorker. His body was found by maid Alice Monaghan when she entered Tesla's room, ignoring the "do not disturb" sign that Tesla had placed on his door two days earlier. Assistant medical examiner H.W. Wembley examined the body and ruled that the cause of death had been coronary thrombosis (a type of heart attack).

Two days later the Federal Bureau of Investigation ordered the Alien Property Custodian to seize Tesla's belongings. John G. Trump, a professor at M.I.T. and a well-known electrical engineer serving as a technical aide to the National Defense Research Committee, was called in to analyze the Tesla items. After a three-day investigation, Trump's report concluded that there was nothing which would constitute a hazard in unfriendly hands, stating:

His [Tesla's] thoughts and efforts during at least the past 15 years were primarily of a speculative, philosophical, and somewhat promotional character often concerned with the production and wireless transmission of power; but did not include new, sound, workable principles or methods for realizing such results.[234]

In a box purported to contain a part of Tesla's "death ray", Trump found a 45-year-old multidecade resistance box.[235]

On 10 January 1943, New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia read a eulogy written by Slovene-American author Louis Adamic live over WNYC radio while violin pieces "Ave Maria" and "Tamo daleko" were played in the background. On 12 January, two thousand people attended a state funeral for Tesla at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan. After the funeral, Tesla's body was taken to the Ferncliff Cemetery in Ardsley, New York, where it was later cremated. The following day, a second service was conducted by prominent priests in the Trinity Chapel (today's Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Sava) in New York City.

Personal life and character

Tesla was a lifelong bachelor, who had once explained that his chastity was very helpful to his scientific abilities.[236] In an interview with the Galveston Daily News on 10 August 1924 he stated, "Now the soft-voiced gentlewoman of my reverent worship has all but vanished. In her place has come the woman who thinks that her chief success in life lies in making herself as much as possible like man—in dress, voice and actions..."[211] Although he told a reporter in later years that he sometimes felt that by not marrying, he had made too great a sacrifice to his work,[209] Tesla chose to never pursue or engage in any known relationships, instead finding all the stimulation he needed in his work.

Tesla was asocial and prone to seclude himself with his work.[137][237][238] However, when he did engage in social life, many people spoke very positively and admiringly of Tesla. Robert Underwood Johnson described him as attaining a "distinguished sweetness, sincerity, modesty, refinement, generosity, and force".[239] His secretary, Dorothy Skerrit, wrote: "his genial smile and nobility of bearing always denoted the gentlemanly characteristics that were so ingrained in his soul".[240] Tesla's friend, Julian Hawthorne, wrote, "seldom did one meet a scientist or engineer who was also a poet, a philosopher, an appreciator of fine music, a linguist, and a connoisseur of food and drink".[241]

Tesla was a good friend of Francis Marion Crawford, Robert Underwood Johnson,[242] Stanford White,[243] Fritz Lowenstein, George Scherff, and Kenneth Swezey.[244][245][246] In middle age, Tesla became a close friend of Mark Twain; they spent a lot of time together in his lab and elsewhere.[242] Twain notably described Tesla's induction motor invention as "the most valuable patent since the telephone".[247] At a party thrown by actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1896, Tesla met Indian Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda. Vivekananda later wrote that Tesla said he could demonstrate mathematically the relationship between matter and energy, something Vivekananda hoped would give a scientific foundation to Vedantic cosmology.[248][249] The meeting with Swami Vivekananda stimulated Tesla's interest in Eastern Science, which led to Tesla studying Hindu and Vedic philosophy for a number of years.[250] Tesla later wrote an article titled "Man's Greatest Achievement" using Sanskrit terms akasha and prana to describe the relationship between matter and energy.[251][252] In the late 1920s, Tesla befriended George Sylvester Viereck, a poet, writer, mystic, and later, a Nazi propagandist. Tesla occasionally attended dinner parties held by Viereck and his wife.[253][254]

Tesla could be harsh at times and openly expressed disgust for overweight people, such as when he fired a secretary because of her weight.[255] He was quick to criticize clothing; on several occasions, Tesla directed a subordinate to go home and change her dress.[236] When Thomas Edison died in 1931, Tesla contributed the only negative opinion to The New York Times, buried in an extensive coverage of Edison's life:

He had no hobby, cared for no sort of amusement of any kind and lived in utter disregard of the most elementary rules of hygiene ... His method was inefficient in the extreme, for an immense ground had to be covered to get anything at all unless blind chance intervened and, at first, I was almost a sorry witness of his doings, knowing that just a little theory and calculation would have saved him 90 percent of the labor. But he had a veritable contempt for book learning and mathematical knowledge, trusting himself entirely to his inventor's instinct and practical American sense.[256][257]

Tesla became a vegetarian in his later years, living on only milk, bread, honey, and vegetable juices.[223][258]

Views and beliefs

On experimental and theoretical physics

Tesla disagreed with the theory of atoms being composed of smaller subatomic particles, stating there was no such thing as an electron creating an electric charge. He believed that if electrons existed at all, they were some fourth state of matter or "sub-atom" that could exist only in an experimental vacuum and that they had nothing to do with electricity.[259][260] Tesla believed that atoms are immutable—they could not change state or be split in any way. He was a believer in the 19th-century concept of an all-pervasive ether that transmitted electrical energy.[261]

Tesla was generally antagonistic towards theories about the conversion of matter into energy.[262] He was also critical of Einstein's theory of relativity, saying:

I hold that space cannot be curved, for the simple reason that it can have no properties. It might as well be said that God has properties. He has not, but only attributes and these are of our own making. Of properties we can only speak when dealing with matter filling the space. To say that in the presence of large bodies space becomes curved is equivalent to stating that something can act upon nothing. I, for one, refuse to subscribe to such a view.[263]

In 1935 he described relativity as "a beggar wrapped in purple whom ignorant people take for a king" and said his own experiments had measured the speed of cosmic rays from Arcturus as fifty times the speed of light.[264]

Tesla claimed to have developed his own physical principle regarding matter and energy that he started working on in 1892,[262] and in 1937, at age 81, claimed in a letter to have completed a "dynamic theory of gravity" that "[would] put an end to idle speculations and false conceptions, as that of curved space". He stated that the theory was "worked out in all details" and that he hoped to soon give it to the world.[265] Further elucidation of his theory was never found in his writings.[266]

On society

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eugenics Movement |

|---|

Tesla is widely considered by his biographers to have been a humanist in philosophical outlook.[267][268] This did not preclude Tesla, like many of his era, from becoming a proponent of an imposed selective breeding version of eugenics.

Tesla expressed the belief that human "pity" had come to interfere with the natural "ruthless workings of nature". Though his argumentation did not depend on a concept of a "master race" or the inherent superiority of one person over another, he advocated for eugenics. In a 1937 interview he stated:

... man's new sense of pity began to interfere with the ruthless workings of nature. The only method compatible with our notions of civilization and the race is to prevent the breeding of the unfit by sterilization and the deliberate guidance of the mating instinct ... The trend of opinion among eugenists is that we must make marriage more difficult. Certainly no one who is not a desirable parent should be permitted to produce progeny. A century from now it will no more occur to a normal person to mate with a person eugenically unfit than to marry a habitual criminal.[269]

In 1926, Tesla commented on the ills of the social subservience of women and the struggle of women toward gender equality, and indicated that humanity's future would be run by "Queen Bees". He believed that women would become the dominant sex in the future.[270]

Tesla made predictions about the relevant issues of a post-World War I environment in a printed article entitled "Science and Discovery are the great Forces which will lead to the Consummation of the War" (20 December 1914).[271] Tesla believed that the League of Nations was not a remedy for the times and issues.[31][better source needed]

On religion

Tesla was raised an Orthodox Christian. Later in life he did not consider himself to be a "believer in the orthodox sense", said he opposed religious fanaticism, and said "Buddhism and Christianity are the greatest religions both in number of disciples and in importance."[272] He also said "To me, the universe is simply a great machine which never came into being and never will end" and "what we call 'soul' or 'spirit,' is nothing more than the sum of the functionings of the body. When this functioning ceases, the 'soul' or the 'spirit' ceases likewise."[272]

Literary works

Tesla wrote a number of books and articles for magazines and journals.[273] Among his books are My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla, compiled and edited by Ben Johnston in 1983 from a series of 1919 magazine articles by Tesla which were republished in 1977; The Fantastic Inventions of Nikola Tesla (1993), compiled and edited by David Hatcher Childress; and The Tesla Papers.

Many of Tesla's writings are freely available online,[274] including the article "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy", published in The Century Magazine in 1900,[275] and the article "Experiments with Alternate Currents of High Potential and High Frequency", published in his book Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla.[276][277]

Legacy and honors

In 1952, following pressure from Tesla's nephew, influential Yugoslav politician Sava Kosanović, Tesla's entire estate was shipped to Belgrade in 80 trunks marked N.T. In 1957, Kosanović's secretary Charlotte Muzar transported Tesla's ashes from the United States to Belgrade. The ashes are displayed in a gold-plated sphere on a marble pedestal in the Nikola Tesla Museum.[278]

Tesla obtained around 300 patents worldwide for his inventions.[279] Some of Tesla's patents are not accounted for, and various sources have discovered some that have lain hidden in patent archives. There are a minimum of 278 known patents[279] issued to Tesla in 26 countries. Many of Tesla's patents were in the United States, Britain, and Canada, but many other patents were approved in countries around the globe.[280] Many inventions developed by Tesla were not put into patent protection.[citation needed]

See also

- Atmospheric electricity – Electricity in planetary atmospheres

- Michael Faraday – English physicist and chemist (1791–1867)

- Charles Proteus Steinmetz – American mathematician and electrical engineer (1865–1923)

- Telluric current – Natural electric current in the Earth's crust

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Tesla does not mention which professor this was by name, but some sources conclude this was Martin Sekulić.[24][25]

- ^ Tesla's contemporaries remembered that on a previous occasion Machine Works manager Batchelor had been unwilling to give Tesla a $7 a week pay raise [56]

- ^ Account comes from a letter Tesla sent in 1938 on the occasion of receiving an award from the National Institute of Immigrant Welfare[64]

- ^ Tesla's own experiments led him to erroneously believe Hertz had misidentified a form of conduction instead of a new form of electromagnetic radiation, an incorrect assumption that Tesla held for a couple of decades.[141][142]

Citations

- ^ Jonnes 2004, p. 355.

- ^ "Tesla" Archived 24 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Burgan 2009, p. 9.

- ^ "Electrical pioneer Tesla honoured". BBC News. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Laplante, Phillip A. (1999). Comprehensive Dictionary of Electrical Engineering 1999. Springer. p. 635. ISBN 978-3-540-64835-2.

- ^ O'Shei, Tim (2008). Marconi and Tesla: Pioneers of Radio Communication. MyReportLinks.com Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-59845-076-7.

- ^ Van Riper 2011, p. 150

- ^ "Pictures of Tesla's home in Smiljan, Croatia and his father's church after rebuilding". Tesla Memorial Society of NY. Archived from the original on 2 June 2003. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Cheney, Uth & Glenn 1999, p. 143.

- ^ O'Neill 1944, pp. 9, 12.

- ^ a b Carlson 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Dommermuth-Costa 1994, p. 12, "Milutin, Nikola's father, was a well-educated priest of the Serbian Orthodox Church.".

- ^ Cheney 2011, p. 25, "The tiny house in which he was born stood next to the Serbian Orthodox Church presided over by his father, the Reverend Milutin Tesla, who sometimes wrote articles under the nom-de-plume 'Man of Justice'".

- ^ Burgan 2009, p. 17, "Nikola's father, Milutin was a Serbian Orthodox priest and had been sent to Smiljan by his church.".

- ^ O'Neill 1944, p. 10.

- ^ Cheney 2001, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Seifer 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 21.

- ^ Seifer 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola; Marinčić, Aleksandar (2008). From Colorado Springs to Long Island: research notes. Belgrade: Nikola Tesla Museum. ISBN 978-86-81243-44-2.

- ^ Budiansky, Stephen (2021). Journey to the edge of reason : the life of Kurt Gödel (First ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-324-00545-2.

In the natural sciences, Austria produced a remarkable number of talented theorists and experimentalists. The electrical genius Nikola Tesla, from Croatia, studied in Karlovac at one of the rigorous German-language high schools, the Gymnasiums, established throughout the Austrian Empire.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wohinz 2019, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Seifer 1998, CHILDHOOD 1856-74.

- ^ Petešić 1976, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 32.

- ^ "Tesla Life and Legacy – Tesla's Early Years". PBS. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ O'Neill 1944, p. 33.

- ^ Glenn, Jim, ed. (1994). The complete patents of Nikola Tesla. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 1-56619-266-8.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d Tesla, Nikola (2011) [1919 edition reprint]. My inventions: the autobiography of Nikola Tesla. Eastford: Martino Fine Books. ISBN 978-1-61427-084-3.

- ^ Adelman, Juliana (11 February 2016). "The electricity between Mark Twain and Nikola Tesla". The Irish Times.

- ^ Seifer 2001, p. 14.

- ^ a b O'Neill 1944, p. 39.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 35.

- ^ a b Seifer 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Seifer 2001, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d Carlson 2013, pp. 47.

- ^ Mrkich, D. (2003). Nikola Tesla: The European Years (1st ed.). Ottawa: Commoner's Publishing. ISBN 0-88970-113-X.

- ^ "NYHOTEL". Tesla Society of NY. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Nikola Tesla: The Genius Who Lit the World". Top Documentary Films. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Carlson 2013, p. 70.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 69.

- ^ O'Neill 1944, pp. 57–60.

- ^ a b c d "Edison & Tesla – The Edison Papers". edison.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Carey, Charles W. (1989). American inventors, entrepreneurs & business visionaries. Infobase Publishing. p. 337. ISBN 0-8160-4559-3. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ a b Carlson 2013, pp. 71–73.

- ^ a b Radmilo Ivanković' Dragan Petrović, review of the reprinted "Nikola Tesla: Notebook from the Edison Machine Works 1884–1885" Archived 26 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 86-81243-11-X, teslauniverse.com

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Seifer 2001, pp. 25, 34.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 69–73.

- ^ "Nikola Tesla, My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla, originally published: 1919, p. 19" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ O'Neill 1944, p. 64.

- ^ Pickover 1999, p. 14

- ^ Seifer – Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla, p. 38

- ^ Jonnes 2004, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Seifer 2001, p. 38.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 73.

- ^ a b Jonnes 2004, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Seifer 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Jonnes 2004, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Carlson 2013, p. 75.

- ^ Ratzlaff, John T., ed. (1984). Tesla Said. Millbrae, California: Tesla Book Co. p. 280. ISBN 0-914119-00-1.

- ^ Charles Fletcher Peck of Englewood, New Jersey per [1] Archived 8 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Carlson 2013, p. 80.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930. JHU Press. March 1993. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8018-4614-4. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ Thomas Parke Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930, pp. 115–118

- ^ Ltd, Nmsi Trading; Institution, Smithsonian (1998). Robert Bud, Instruments of Science: An Historical Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8153-1561-2. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ a b Jonnes 2004, p. 161.

- ^ Henry G. Prout, A Life of George Westinghouse, p. 129

- ^ a b Carlson 2013, p. 105-106.

- ^ Froehlich, Fritz E.; Kent, Allen (December 1998). The Froehlich/Kent Encyclopedia of Telecommunications: Volume 17. CRC Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8247-2915-8. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Jonnes 2004, p. 160–162.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 108–111.

- ^ a b c d 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Klooster 2009, p. 305.

- ^ Harris, William (14 July 2008). "William Harris, How did Nikola Tesla change the way we use energy?". Science.howstuffworks.com. p. 3. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Munson, Richard (2005). From Edison to Enron: The Business of Power and What It Means for the Future of Electricity. Westport, CT: Praeger. pp. 24–42. ISBN 978-0-275-98740-4.

- ^ Quentin R. Skrabec (2007). George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius, Algora Publishing, pp. 119–121

- ^ Robert L. Bradley, Jr. (2011). Edison to Enron: Energy Markets and Political Strategies, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 55–58

- ^ Quentin R. Skrabec (2007). George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius, Algora Publishing, pp. 118–120

- ^ Seifer 1998, p. 47.

- ^ a b Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). George Westinghouse : gentle genius. New York: Algora Pub. ISBN 978-0-87586-506-5.

- ^ a b c Carlson 2013, p. 130.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 131.

- ^ Jonnes 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Thomas Parke Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930 (1983), p. 119

- ^ a b Jonnes 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Cheney 2001, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Christopher Cooper, The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation, Race Point Publishing. 2015, p. 109

- ^ Electricity, a Popular Electrical Journal, Volume 13, No. 4, 4 August 1897, Electricity Newspaper Company, pp. 50 Google Books Archived 28 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rybak, James P. (November 1999). "Nikola Tesla: Scientific Savant from the Tesla Universe Article Collection". Popular Electronics: 40–48 & 88. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press, p. 218

- ^ "Laboratories in New York (1889–1902)". Open Tesla Research. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 122.

- ^ "Tesla coil". Museum of Electricity and Magnetism, Center for Learning. National High Magnetic Field Laboratory website, Florida State Univ. 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 124.

- ^ Burnett, Richie (2008). "Operation of the Tesla Coil". Richie's Tesla Coil Web Page. Richard Burnett private website. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ "Naturalization Record of Nikola Tesla, 30 July 1891". Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021., Naturalization Index, NYC Courts, referenced in Carlson (2013), Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, p. H-41

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Uth, Robert (12 December 2000). "Tesla coil". Tesla: Master of Lightning. PBS.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (20 May 1891). Experiments with Alternate Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2017., lecture delivered before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Columbia College, New York. Reprinted as a book of the same name by. Wildside Press. 2006. ISBN 0-8095-0162-7. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 132.

- ^ Christopher Cooper (2015). The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation, Race Point Publishing, pp. 143–144

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Orton, John (2004). The Story of Semiconductors. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 53.

- ^ Corum, Kenneth L. & Corum, James F. "Tesla's Connection to Columbia University" (PDF). Tesla Memorial Society of NY. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 166.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Moran, Richard (2007). Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 222.

- ^ Rosenberg, Chaim M. (20 February 2008). America at the Fair: Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2521-1. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Bertuca, David J.; Hartman, Donald K. & Neumeister, Susan M. (1996). The World's Columbian Exposition: A Centennial Bibliographic Guide. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. xxi. ISBN 978-0-313-26644-7. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Hugo Gernsback, "Tesla's Egg of Columbus, How Tesla Performed the Feat of Columbus Without Cracking the Egg" Electrical Experimenter, 19 March 1919, p. 774 [2] Archived 27 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Seifer 2001, p. 120.

- ^ Thomas Commerford Martin, The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla: With Special Reference to His Work in Polyphase Currents and High Potential Lighting, Electrical Engineer – 1894, Chapter XLII, page 485 [3]

- ^ Cheney 2001, p. 76.

- ^ Cheney 2001, p. 79.

- ^ Barrett, John Patrick (1894). Electricity at the Columbian Exposition; Including an Account of the Exhibits in the Electricity Building, the Power Plant in Machinery Hall. R. R. Donnelley. pp. 268–269. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ Carlson 2013, p. 182.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 181–185.

- ^ Reciprocating Engine, U.S. patent 514,169, 6 February 1894.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 167–173.

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Mr. Tesla's Great Loss, All of the Electrician’s Valuable Instruments Burned, WORK OF HALF A LIFETIME GONE, New York Times, 14 March 1895 (archived at teslauniverse.com Archived 28 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (2007). X-ray vision: Nikola Tesla on Roentgen rays (1st ed.). Radford, VA: Wiilder Publications. ISBN 978-1-934451-92-2.

- ^ Cheney 2001, p. 134.

- ^ RADIOGRAPHY – EXPERIMENTS MADE BY NIKOLA TESLA – Shoulder of a Man Taken Through His Clothing—Chalky Deposits Infallibly Detected, The Constitution, Atlanta, Georgia, Friday 13, March 1896, p. 9 online archive Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine