William Byrd

| Part of a series on |

| Renaissance music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

|

|

William Byrd (/bɜːrd/; c. 1540 – 4 July 1623) was an English Renaissance composer. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native country and on the Continent.[1] He is often considered along with John Dunstaple and Henry Purcell as one of England's most important composers of early music.[2]

Byrd wrote in many of the forms current in England at the time, including various types of sacred and secular polyphony, keyboard (the so-called Virginalist school), and consort music. He produced sacred music for Anglican services, but during the 1570's became a Roman Catholic, and wrote Catholic sacred music later in his life.

Life

[edit]Birth and background

[edit]Richard Byrd of Ingatestone, Essex, the paternal grandfather of Thomas Byrd, probably moved to London in the 15th century. Thereafter succeeding generations of the Byrd family are described as gentlemen.[3]

William Byrd was probably born in London, the third surviving son of Thomas Byrd and his wife, Margery.[4][note 1] No record of his birth has survived,[5] and the year of his birth is not known for certain, but a document dated 2 October 1598, and written by William Byrd, states that he is "58 yeares or ther abouts", making the year he was born to be 1539 or 1540.[6] Byrd's will of November 1622 provides a later date for his birth, as in it Byrd states that he was then in the "80th year of mine age". The historian Kerry McCarthy has suggested that discrepancy over these dates may have been due to the will not being kept up to date over a period of several years.[7]

Byrd was born into a musical and relatively wealthy family.[8] He had two older brothers, Symond and John,[5] who became London merchants and active members of their respective livery companies. One of his four sisters, Barbara, was married to a maker of musical instruments who kept a shop; his three other sisters, Martha, Mary and Alice, were probably also married to merchants.[8][9]

Youth and early career

[edit]Details of Byrd's childhood are speculative.[8] There is no documentary evidence concerning Byrd's education or early musical training. His two brothers were choristers at St. Paul's Cathedral,[5] and Byrd may have been a chorister there as well, although it is possible that he was a chorister with the Chapel Royal. According to Anthony Wood, Byrd was "bred up to musick under Tho. Tallis",[10] and a reference in the Cantiones sacrae, published by Byrd and Thomas Tallis in 1575, tends to confirm that Byrd was a pupil of Tallis in the Chapel Royal.[11] If he was—and conclusive evidence has not emerged to verify it[12]—it seems likely that once Byrd's voice broke, the boy stayed on at the Chapel Royal as Tallis's assistant.[5]

Byrd produced student compositions, including Sermone Blando for consort, and a "Miserere". Church music for the Catholic rite reintroduced by Mary would have been composed before her death in 1558, which occurred when Byrd was eighteen.[5] His early compositions suggest he was taught polyphony when a student.[13]

Lincoln

[edit]

Byrd's first known professional employment was his appointment in 1563 as organist and master of the choristers at Lincoln Cathedral. Residing at what is now 6 Minster Yard Lincoln, he remained in post until 1572.[14] His period at Lincoln was not entirely trouble-free, for on 19 November 1569 the Dean and Chapter cited him for 'certain matters alleged against him' as the result of which his salary was suspended. Since Puritanism was influential at Lincoln, it is possible that the allegations were connected with over-elaborate choral polyphony or organ playing. A second directive, dated 29 November, issued detailed instructions regarding Byrd's use of the organ in the liturgy.[15]

On 14 September 1568, Byrd was married in the church of St Margaret-in-the-Close, Lincoln. His wife, Juliana, came from the Birley family of Lincolnshire. The baptism records mention two of their children, Christopher and Elizabeth,[16] but the marriage produced at least seven children.

The Chapel Royal

[edit]

In 1572, following the death of the composer Robert Parsons, who drowned in the Trent near Newark on 25 January of that year, Byrd obtained the post of Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, the largest choir of its kind in England. The appointment, which was for life, came with a good salary.[17] Almost from the outset Byrd is named as 'organist', which however was not a designated post but an occupation for any Chapel Royal member capable of filling it.

Byrd's appointment at the Chapel Royal increased his opportunities to widen his scope as a composer and also to make contacts at the court of Queen Elizabeth. The Queen was a moderate Protestant who eschewed the more extreme forms of Puritanism and retained a fondness for elaborate ritual, besides being a music lover and keyboard player herself. Byrd's output of Anglican church music (defined in the strictest sense as sacred music designed for performance in church) is small, but it stretches the limits of elaboration then regarded as acceptable by some reforming Protestants who regarded highly wrought music as a distraction from the Word of God.

In 1575 Byrd and Tallis were jointly granted a monopoly for the printing of music and ruled music paper for 21 years, one of a number of patents issued by the Crown for the printing of books, which was the first known issuing of letters patent.[18] The two musicians used the services of the French Huguenot printer Thomas Vautrollier, who had settled in England and previously produced an edition of a collection of Lassus chansons in London (Receuil du mellange, 1570).

The two monopolists took advantage of the patent to produce a grandiose joint publication under the title Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur. It was a collection of 34 Latin motets dedicated to the Queen herself, accompanied by elaborate prefatory matter including poems in Latin elegiacs by the schoolmaster Richard Mulcaster and the young courtier Ferdinand Heybourne (aka Richardson). There are 17 motets each by Tallis and Byrd, one for each year of the Queen's reign.

The Cantiones were a financial failure. In 1577 Byrd and Tallis were forced to petition Queen Elizabeth for financial help, pleading that the publication had "fallen oute to oure greate losse" and that Tallis was now "verie aged". They were subsequently granted the leasehold on various lands in East Anglia and the West Country for a period of 21 years.[19]

Catholicism

[edit]From the early 1570s onwards Byrd became increasingly involved with Catholicism, which, as the scholarship of the last half-century has demonstrated, became a major factor in his personal and creative life. As John Harley has shown, it is probable that Byrd's parental family were Protestants, though whether by deeply felt conviction or nominal conformism is not clear. Byrd himself may have held Protestant beliefs in his youth, for a recently discovered fragment of a setting of an English translation of Martin Luther's hymn "Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort", which bears an attribution to "Birde" includes the line "From Turk and Pope defend us Lord".[20] However, from the 1570s onwards he is found associating with known Catholics, including Lord Thomas Paget, to whom he wrote a petitionary letter on behalf of an unnamed friend in about 1573.[21] Byrd's wife Julian was first cited for recusancy (refusing to attend Anglican services) at Harlington in Middlesex, where the family then lived, in 1577. Byrd himself appears in the recusancy lists from 1584.[22]

His involvement with Catholicism took on a new dimension in the 1580s. Following Pope Pius V's papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, in 1570, which absolved Elizabeth's subjects from allegiance to her and effectively made her an outlaw in the eyes of the Catholic Church, Catholicism became increasingly identified with sedition in the eyes of the Tudor authorities. With the influx of missionary priests trained at the English College, Douai (now in France but then part of the Spanish Netherlands), and in Rome from the 1570s onwards, relations between the authorities and the Catholic community took a further turn for the worse. Byrd himself is found in the company of prominent Catholics. In 1583 he got into serious trouble because of his association with Paget, who was suspected of involvement in the Throckmorton Plot, and for sending money to Catholics abroad. As a result of this, Byrd's membership of the Chapel Royal was apparently suspended for a time, restrictions were placed on his movements, and his house was placed on the search list. In 1586 he attended a gathering at a country house in the company of Father Henry Garnett (later executed for complicity in the Gunpowder Plot) and the Catholic poet Robert Southwell.[23]

Stondon Massey

[edit]In about 1594 Byrd's career entered a new phase. He was now in his early fifties, and seems to have gone into semi-retirement from the Chapel Royal. He moved with his family from Harlington to Stondon Massey, a small village near Chipping Ongar in Essex.[24] His ownership of Stondon Place, where he lived for the rest of his life, was contested by Joanna Shelley, with whom he engaged in a legal dispute lasting about a decade and a half. The main reason for the move was apparently the proximity of Byrd's patron Sir John Petre, son of Sir William Petre. A wealthy local landowner, Petre was a discreet Catholic who maintained two local manor houses, Ingatestone Hall and Thorndon Hall, the first of which still survives in a much-altered state (the latter has been rebuilt). Petre held clandestine Mass celebrations, with music provided by his servants, which were subject to the unwelcome attention of spies and paid informers working for the Crown.

Byrd's acquaintance with the Petre family extended back at least to 1581 (as his surviving autograph letter of that year shows)[25] and he spent two weeks at the Petre household over Christmas in 1589. He was ideally equipped to provide elaborate polyphony to adorn the music making at the Catholic country houses of the time. The ongoing adherence of Byrd and his family to Catholicism continued to cause him difficulties, though a surviving reference to a lost petition apparently written by Byrd to Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury sometime between 1605 and 1612 suggests that he had been allowed to practise his religion under licence during the reign of Elizabeth.[26] Nevertheless, he regularly appeared in the quarterly local assizes and was reported to the archdeaconry court for non-attendance at the parish church. He was required to pay heavy fines for recusancy.

Anglican church music

[edit]Byrd's staunch adherence to Catholicism did not prevent him from contributing memorably to the repertory of Anglican church music. Byrd's small output of church anthems ranges in style from relatively sober early examples (O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth our queen (a6) and How long shall mine enemies (a5) ) to other, evidently late works such as Sing joyfully (a6) which is close in style to the English motets of Byrd's 1611 set, discussed below. Byrd also played a role in the emergence of the new verse anthem, which seems to have evolved in part from the practice of adding vocal refrains to consort songs. Byrd's four Anglican service settings range in style from the unpretentious Short Service, already discussed, to the magnificent so-called Great Service, a grandiose work which continues a tradition of opulent settings by Richard Farrant, William Mundy and Parsons. Byrd's setting is on a massive scale, requiring five-part Decani and Cantoris groupings in antiphony, block homophony and five, six and eight-part counterpoint with verse (solo) sections for added variety. This service setting, which includes an organ part, must have been sung by the Chapel Royal Choir on major liturgical occasions in the early seventeenth century, though its limited circulation suggests that many other cathedral choirs must have found it beyond them. Nevertheless, the source material shows that it was sung in York Minster as well as Durham, Worcester and Cambridge, in the early seventeenth century. The Great Service was in existence by 1606 (the last copying date entered in the so-called Baldwin Commonplace Book) and may date back as far as the 1590s. Kerry McCarthy has pointed out that the York Minster manuscript of the Great Service was copied by a vicar-choral named John Todd, apparently between 1597 and 1599, and is described as 'Mr Byrd's new sute of service for means'.[27] This suggests the possibility that the work may have been Byrd's next compositional project after the three Mass settings.

Later years

[edit]During his later years Byrd also added to his output of consort songs, a number of which were discovered by Philip Brett and Thurston Dart when Brett was a university student in the early 1960s.[28] They probably reflect Byrd's relationship with the Norfolk landowner and music-lover Sir Edward Paston (1550–1630) who may have written some of the poems. The songs include elegies for public figures such as the Earl of Essex (1601), the Catholic matriarch and viscountess Montague Magdalen Dacre (With Lilies White, 1608) and Henry Prince of Wales (1612). Others refer to local notabilities or incidents from the Norfolk area.

Byrd remained in Stondon Massey until his death, due to heart failure, on 4 July 1623, which was noted in the Chapel Royal Check Book in a unique entry describing him as "a Father of Musick". Despite repeated citations for recusancy and persistent heavy fines, he died a rich man, having rooms at the time of his death at the London home of the Earl of Worcester.

Music

[edit]During his lifetime, Byrd published three volumes of Cantiones Sacrae (1575, co-written with Tallis; 1589; 1591), two volumes of Gradualia (1605; 1607), Psalmes, Sonets, and Songs of Sadnes and Pietie (1588), Songs of Sundrie Natures (1589), and Psalmes, Songs, and Sonnets (1611). He also composed other vocal and instrumental pieces; three Masses, music for the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, and motets.[29]

Early compositions

[edit]One of Byrd's earliest compositions was a collaboration with two Chapel Royal singing-men, John Sheppard and William Mundy, on a setting for four male voices of the psalm In exitu Israel for the procession to the font in Easter week. It was probably composed near the end of the reign of Queen Mary Tudor (1553–1558),[10] who revived Sarum liturgical practices.

A few other compositions by Byrd also probably date from his teenage years. These include his setting of the Easter responsory Christus resurgens (a4) which was not published until 1605, but which as part of the Sarum liturgy could also have been composed during Mary's reign, as well as Alleluia confitemini (a3) which combines two liturgical items for Easter week. Some of the hymns and antiphons for keyboard and for consort may also date from this period, though it is also possible that the consort pieces may have been composed in Lincoln for the musical training of choirboys.

The 1560s were also important formative years for Byrd the composer. His Short Service, an unpretentious setting of items for the Anglican Matins, Communion and Evensong services, which seems to have been designed to comply with the Protestant reformers' demand for clear words and simple musical textures, may well have been composed during the Lincoln years. It is at any rate clear that Byrd was composing Anglican church music, for when he left Lincoln the Dean and Chapter continued to pay him at a reduced rate on condition that he would send the cathedral his compositions. Byrd had also taken serious strides with instrumental music. The seven In Nomine settings for consort (two a4 and five a5), at least one of the consort fantasias (Neighbour F1 a6) and a number of important keyboard works were apparently composed during the Lincoln years. The latter include the Ground in Gamut (described as "Mr Byrd's old ground") by his future pupil Thomas Tomkins, the A minor Fantasia, and probably the first of Byrd's great series of keyboard pavanes and galliards, a composition which was transcribed by Byrd from an original for five-part consort. All these show Byrd gradually emerging as a major figure on the Elizabethan musical landscape.

Some sets of keyboard variations, such as The Hunt's Up and the imperfectly preserved set on Gypsies' Round also seem to be early works. As we have seen, Byrd had begun setting Latin liturgical texts as a teenager, and he seems to have continued to do so at Lincoln. Two exceptional large-scale psalm motets, Ad Dominum cum tribularer (a8) and Domine quis habitabit (a9), are Byrd's contribution to a paraliturgical form cultivated by Robert White and Parsons. De lamentatione, another early work, is a contribution to the Elizabethan practice of setting groups of verses from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, following the format of the Tenebrae lessons sung in the Catholic rite during the last three days of Holy Week. Other contributors in this form include Tallis, White, Parsons and the elder Ferrabosco. It is likely that this practice was an expression of Elizabethan Catholic nostalgia, as a number of the texts suggest.

Cantiones sacrae (1575)

[edit]Byrd's contributions to the Cantiones are in various different styles, although his forceful musical personality is stamped on all of them. The inclusion of Laudate pueri (a6) which proves to be an instrumental fantasia with words added after composition,[30] is one sign that Byrd had some difficulty in assembling enough material for the collection. Diliges Dominum (a8), which may also originally have been untexted, is an eight-in-four retrograde canon of little musical interest. Also belonging to the more archaic stratum of motets is Libera me Domine (a5), a cantus firmus setting of the ninth responsory at Matins for the Office for the Dead, which takes its point of departure from the setting by Parsons, while Miserere mihi (a6), a setting of a Compline antiphon often used by Tudor composers for didactic cantus firmus exercises, incorporates a four-in-two canon. Tribue Domine (a6) is a large-scale sectional composition setting from a medieval collection of Meditationes which was commonly attributed to St Augustine,[31] composed in a style which owes much to earlier Tudor settings of votive antiphons as a mosaic of full and semichoir passages. Byrd sets it in three sections, each beginning with a semichoir passage in archaic style.

Byrd's contribution to the Cantiones also includes compositions in a more forward-looking manner which point the way to his motets of the 1580s. Some of them show the influence of the motets of Ferrabosco I, a Bolognese musician who worked in the Tudor court at intervals between 1562 and 1578.[32] Ferrabosco's motets provided direct models for Byrd's Emendemus in melius (a5), O lux beata Trinitas (a6), Domine secundum actum meum (a6) and Siderum rector (a5) as well as a more generalised paradigm for what Joseph Kerman has called Byrd's 'affective-imitative' style, a method of setting pathetic texts in extended paragraphs based on subjects employing curving lines in fluid rhythm and contrapuntal techniques which Byrd learnt from his study of Ferrabosco.

Cantiones sacrae (1589 and 1591)

[edit]Byrd's commitment to the Catholic cause found expression in his motets, of which he composed about 50 between 1575 and 1591. While the texts of the motets included by Byrd and Tallis in the 1575 Cantiones have a High Anglican doctrinal tone, scholars such as Joseph Kerman have detected a profound change of direction in the texts which Byrd set in the motets of the 1580s.[33] In particular there is a persistent emphasis on themes such as the persecution of the chosen people (Domine praestolamur a5) the Babylonian or Egyptian captivity (Domine tu iurasti) and the long-awaited coming of deliverance (Laetentur caeli, Circumspice Jerusalem). This has led scholars from Kerman onwards to believe that Byrd was reinterpreting biblical and liturgical texts in a contemporary context and writing laments and petitions on behalf of the persecuted Catholic community, which seems to have adopted Byrd as a kind of 'house' composer. Some texts should probably be interpreted as warnings against spies (Vigilate, nescitis enim) or lying tongues (Quis est homo) or celebration of the memory of martyred priests (O quam gloriosum). Byrd's setting of the first four verses of Psalm 78 (Deus venerunt gentes) is widely believed to refer to the brutal execution of Fr Edmund Campion in 1581 an event that caused widespread revulsion on the Continent as well as in England. Finally, and perhaps most remarkably, Byrd's Quomodo cantabimus is the result of a motet exchange between Byrd and Philippe de Monte, who was director of music to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, in Prague. In 1583 De Monte sent Byrd his setting of verses 1–4 of Vulgate Psalm 136 (Super flumina Babylonis), including the pointed question "How shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?" Byrd replied the following year with a setting of the defiant continuation, set, like de Monte's piece, in eight parts and incorporating a three-part canon by inversion.

Thirty-seven of Byrd's motets were published in two sets of Cantiones sacrae, which appeared in 1589 and 1591. Together with two sets of English songs, discussed below, these collections, dedicated to powerful Elizabethan lords (Edward Somerset, 4th Earl of Worcester and John Lumley, 1st Baron Lumley), probably formed part of Byrd's campaign to re-establish himself in Court circles after the reverses of the 1580s. They may also reflect the fact that Byrd's fellow monopolist Tallis and his printer Thomas Vautrollier had died, thus creating a more propitious climate for publishing ventures. Since many of the motet texts of the 1589 and 1591 sets are pathetic in tone, it is not surprising that many of them continue and develop the 'affective-imitative' vein found in some motets from the 1570s, though in a more concise and concentrated form. Domine praestolamur (1589) is a good example of this style, laid out in imitative paragraphs based on subjects which characteristically emphasise the expressive minor second and minor sixth, with continuations which subsequently break off and are heard separately (another technique which Byrd had learnt from his study of Ferrabosco). Byrd evolved a special "cell" technique for setting the petitionary clauses such as miserere mei or libera nos Domine which form the focal point for a number of the texts. Particularly striking examples of these are the final section of Tribulatio proxima est (1589) and the multi-sectional Infelix ego (1591), a large-scale motet which takes its point of departure from Tribue Domine of 1575.

There are also a number of compositions which do not conform to this stylistic pattern. They include three motets which employ the old-fashioned cantus firmus technique as well as the most famous item in the 1589 collection, Ne irascaris Domine. the second part of which is closely modelled on Philip van Wilder's popular Aspice Domine. A few motets, especially in the 1591 set, abandon traditional motet style and resort to vivid word painting which reflects the growing popularity of the madrigal (Haec dies, Laudibus in sanctis, 1591). A famous passage from Thomas Morley's A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1597) supports the view that the madrigal had superseded the motet in the favour of Catholic patrons, a fact which may explain why Byrd composed few non-liturgical motets after 1591.

The English song-books of 1588 and 1589

[edit]In 1588 and 1589 Byrd also published two collections of English songs.[34] The first, Psalms, Sonnets and Songs of Sadness and Pietie (1588), contains the first madrigals published in England.[35] It consists mainly of adapted consort songs, which Byrd, probably guided by commercial instincts, had turned into vocal part-songs by adding words to the accompanying instrumental parts and labelling the original solo voice as "the first singing part". The consort song, which was the most popular form of vernacular polyphony in England in the third quarter of the sixteenth century, was a solo song for a high voice (often sung by a boy) accompanied by a consort of four consort instruments (normally viols). As the title of Byrd's collection implies, consort songs varied widely in character. Many were settings of metrical psalms, in which the solo voice sings a melody in the manner of the numerous metrical psalm collections of the day (e.g. Sternhold and Hopkins Psalter, 1562) with each line prefigured by imitation in the accompanying instruments. Others are dramatic elegies, intended to be performed in the boy-plays which were popular in Tudor London. A popular source for song settings was Richard Edwards' The paradyse of dainty devices (1576) of which seven settings in consort song form survive.

Byrd's 1588 collection, which complicates the form as he inherited it from Parsons, Richard Farrant and others, reflects this tradition. The "psalms" section sets texts drawn from Sternhold's psalter of 1549 in the traditional manner, while the 'sonnets and pastorals' section employs lighter, more rapid motion with crotchet (quarter-note) pulse, and sometimes triple metre (Though Amaryllis dance in green, If women could be fair). Poetically, the set (together with other evidence) reflects Byrd's involvement with the literary circle surrounding Sir Philip Sidney, whose influence at Court was at its height in the early 1580s. Byrd set three of the songs from Sidney's sonnet sequence Astrophel and Stella, as well as poems by other members of the Sidney circle, and also included two elegies on Sidney's death in the Battle of Zutphen in 1586.[36] But the most popular item in the set was the Lullaby (Lullay lullaby) which blends the tradition of the dramatic lament with the cradle-songs found in some early boy-plays and medieval mystery plays. It long retained its popularity. In 1602, Byrd's patron Edward Somerset, 4th Earl of Worcester, discussing Court fashions in music, predicted that "in winter lullaby, an owld song of Mr Birde, wylbee more in request as I thinke."

The Songs of Sundrie Natures (1589) contain sections in three, four, five and six parts, a format which follows the plan of many Tudor manuscript collections of household music and was probably intended to emulate the madrigal collection Musica transalpina, which had appeared in print the previous year. Byrd's set contains compositions in a wide variety of musical styles, reflecting the variegated character of the texts which he was setting. The three-part section includes settings of metrical versions of the seven penitential psalms, in an archaic style which reflects the influence of the psalm collections. Other items from the three-part and four-part section are in a lighter vein, employing a line-by-line imitative technique and a predominant crotchet pulse (The nightingale so pleasant (a3), Is love a boy? (a4)). The five-part section includes vocal part-songs which show the influence of the "adapted consort song" style of the 1588 set but which seem to have been conceived as all-vocal part-songs. Byrd also bowed to tradition by setting two carols in the traditional form with alternating verses and burdens, (From Virgin's womb this day did spring, An earthly tree, a heavenly fruit, both a6) and even included an anthem, a setting of the Easter prose Christ rising again which also circulated in church choir manuscripts with organ accompaniment.

My Ladye Nevells Booke

[edit]The 1580s were also a productive decade for Byrd as a composer of instrumental music. On 11 September 1591 John Baldwin, a tenor lay-clerk at St George's Chapel, Windsor and later a colleague of Byrd in the Chapel Royal, completed the copying of My Ladye Nevells Booke, a collection of 42 of Byrd's keyboard pieces, which was probably produced under Byrd's supervision and includes corrections which are thought to be in the composer's hand. Byrd would almost certainly have published it if the technical means had been available to do so. The dedicatee long remained unidentified, but John Harley's researches into the heraldic design on the fly-leaf have shown that she was Lady Elizabeth Neville, the third wife of Sir Henry Neville of Billingbear House, Berkshire, who was a justice of the peace and a warden of Windsor Great Park.[37] Under her third married name, Lady Periam, she also received the dedication of Thomas Morley's two-part canzonets of 1595. The contents show Byrd's mastery of a wide variety of keyboard forms, though liturgical compositions based on plainsong are not represented. The collection includes a series of ten pavans and galliards in the usual three-strain form with embellished repeats of each strain. (The only exception is the Ninth Pavan, which is a set of variations on the passamezzo antico bass.)

There are indications that the sequence may be a chronological one, for the First Pavan is labelled "the first that ever hee made" in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, and the Tenth Pavan, which is separated from the others, evidently became available at a late stage before the completion date. It is dedicated to William Petre (the son of Byrd's patron Sir John Petre, 1st Baron Petre) who was only 15 years old in 1591 and could hardly have played it if it had been composed much earlier. The collection also includes two famous pieces of programme music. The Battle, which was apparently inspired by an unidentified skirmish in Elizabeth's Irish wars, is a sequence of movements bearing titles such as "The marche to fight", "The battells be joyned" and "The Galliarde for the victorie". Although not representing Byrd at his most profound, it achieved great popularity and is of incidental interest for the information which it gives on sixteenth-century English military calls. It is followed by The Barley Break (a mock-battle follows a real one), a light-hearted piece which follows the progress of a game of "barley-break", a version of the game now known as "piggy in the middle", played by three couples with a ball. My Ladye Nevells Booke also contains two monumental Grounds, and sets of keyboard variations of variegated character, notably the huge set on Walsingham and the popular variations on Sellinger's Round, Carman's Whistle and My Lord Willoughby's Welcome Home. The fantasias and voluntaries in Nevell also cover a wide stylistic range, some being austerely contrapuntal (A voluntarie, no. 42) and others lighter and more Italianate in tone. (A Fancie no 36). Like the five-and six-part consort fantasias, they sometimes feature a gradual increase in momentum after an imitative opening paragraph.

Consort music

[edit]The period up to 1591 also saw important additions to Byrd's output of consort music, some of which have probably been lost. Two magnificent large-scale compositions are the Browning, a set of 20 variations on a popular melody (also known as "The leaves be green") which evidently originated as a celebration of the ripening of nuts in autumn, and an elaborate ground on the formula known as the Goodnight Ground. The smaller-scale fantasias (those a3 and a4) use a light-textured imitative style which owes something to Continental models, while the five and six-part fantasias employ large-scale cumulative construction and allusions to snatches of popular songs. A good example of the last type is the Fantasia a6 (No 2) which begins with a sober imitative paragraph before progressively more fragmented textures (working in a quotation from Greensleeves at one point). It even includes a complete three-strain galliard, followed by an expansive coda (for a performance on YouTube, see under 'External links' below). The single five-part fantasia, which is apparently an early work, includes a canon at the upper fourth.[citation needed]

Masses

[edit]Byrd now embarked on a programme to provide a cycle of liturgical music covering all the principal feasts of the Catholic Church calendar. The first stage in this undertaking comprised the three Ordinary of the Mass cycles (in four, three and five parts), which were published by Thomas East between 1592 and 1595. The editions are undated (dates can be established only by close bibliographic analysis),[38] do not name the printer and consist of only one bifolium per partbook to aid concealment, reminders that the possession of heterodox books was still highly dangerous. All three works contain retrospective features harking back to the earlier Tudor tradition of Mass settings which had lapsed after 1558, along with others which reflect Continental influence and the liturgical practices of the foreign-trained incoming missionary priests. Mass for Four Voices, or the Four-Part Mass, which according to Joseph Kerman was probably the first to be composed, is partly modelled on John Taverner's Mean Mass, a highly regarded early Tudor setting which Byrd would probably have sung as a choirboy. Taverner's influence is particularly clear in the scale figures rising successively through a fifth, a sixth and a seventh in Byrd's setting of the Sanctus.

All three Mass cycles employ other early Tudor features, notably the mosaic of semichoir sections alternating with full sections in the four-part and five-part Masses, the use of a semichoir section to open the Gloria, Credo, and Agnus Dei, and the head-motif which links the openings of all the movements of a cycle. However, all three cycles also include Kyries, a rare feature in Sarum Rite Mass settings, which usually omitted it because of the use of tropes on festal occasions in the Sarum Rite. The Kyrie of the three-part Mass is set in a simple litany-like style, but the other Kyrie settings employ dense imitative polyphony. A special feature of the four-part and five-part Masses is Byrd's treatment of the Agnus Dei, which employ the technique which Byrd had previously applied to the petitionary clauses from the motets of the 1589 and 1591 Cantiones sacrae. The final words dona nobis pacem ("grant us peace"), which are set to chains of anguished suspensions in the Four-Part Mass and expressive block homophony in the five-part setting, almost certainly reflect the aspirations of the troubled Catholic community of the 1590s.

Gradualia

[edit]The second stage in Byrd's programme of liturgical polyphony is formed by the Gradualia, two cycles of motets containing 109 items and published in 1605 and 1607. They are dedicated to two members of the Catholic nobility, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton and Byrd's own patron Sir John Petre, who had been elevated to the peerage in 1603 under the title Lord Petre of Writtle. The appearance of these two monumental collections of Catholic polyphony reflects the hopes which the recusant community must have harboured for an easier life under the new king James I, whose mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had been a Catholic. Addressing Petre (who is known to have lent him money to advance the printing of the collection), Byrd describes the contents of the 1607 set as "blooms collected in your own garden and rightfully due to you as tithes", thus making explicit the fact that they had formed part of Catholic religious observances in the Petre household.

The greater part of the two collections consists of settings of the Proprium Missae for the major feasts of the church calendar, thus supplementing the Mass Ordinary cycles which Byrd had published in the 1590s. Normally, Byrd includes the Introit, the Gradual, the Alleluia (or Tract in Lent if needed), the Offertory and Communion. The feasts covered include the major feasts of the Virgin Mary (including the votive masses for the Virgin for the four seasons of the church year), All Saints and Corpus Christi (1605) followed by the feasts of the Temporale (Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, Ascension, Whitsun, and Feast of Saints Peter and Paul (with additional items for St Peter's Chains and the Votive Mass of the Blessed Sacrament) in 1607. The verse of the Introit is normally set as a semichoir section, returning to full choir scoring for the Gloria Patri. Similar treatment applies to the Gradual verse, which is normally attached to the opening Alleluia to form a single item. The liturgy requires repeated settings of the word "Alleluia", and Byrd provides a wide variety of different settings forming brilliantly conceived miniature fantasias which are one of the most striking features of the two sets. The Alleluia verse, together with the closing Alleluia, normally form an item in themselves, while the Offertory and the Communion are set as they stand.

In the Roman liturgy there are many texts which appear repeatedly in different liturgical contexts. To avoid having to set the same text twice, Byrd often resorted to a cross-reference or "transfer" system which allowed a single setting to be slotted into a different place in the liturgy. This practice sometimes causes confusion, partly because normally no rubrics are printed to make the required transfer clear and partly because there are some errors which complicate matters still further. A good example of the transfer system in operation is provided by the first motet from the 1605 set (Suscepimus Deus a5) in which the text used for the Introit has to be reused in a shortened form for the Gradual. Byrd provides a cadential break at the cut-off point.

The 1605 set also contains a number of miscellaneous items which fall outside the liturgical scheme of the main body of the set. As Philip Brett has pointed out, most of the items from the four- and three-part sections were taken from the Primer (the English name for the Book of hours), thus falling within the sphere of private devotions rather than public worship. These include, inter alia, settings of the four Marian antiphons from the Roman Rite, four Marian hymns set a3, a version of the Litany, the gem-like setting of the Eucharistic hymn Ave verum Corpus, and the Turbarum voces from the St John Passion, as well as a series of miscellaneous items.

In stylistic terms the motets of the Gradualia form a sharp contrast to those of the Cantiones sacrae publications. The vast majority are shorter, with the discursive imitative paragraphs of the earlier motets giving place to double phrases in which the counterpoint, though intricate and concentrated, assumes a secondary level of importance. Long imitative paragraphs are the exception, often kept for final climactic sections in the minority of extended motets. The melodic writing often breaks into quaver (eighth-note) motion, tending to undermine the minim (half-note) pulse with surface detail. Some of the more festive items, especially in the 1607 set, feature vivid madrigalesque word-painting. The Marian hymns from the 1605 Gradualia are set in a light line-by-line imitative counterpoint with crotchet pulse which recalls the three-part English songs from Songs of sundrie natures (1589). For obvious reasons, the Gradualia never achieved the popularity of Byrd's earlier works. The 1607 set omits several texts, which were evidently too sensitive for publication in the light of the renewed anti-Catholic persecution which followed the failure of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. A contemporary account which sheds light on the circulation of the music between Catholic country houses, refers to the arrest of a young Frenchman named Charles de Ligny, who was followed from an unidentified country house by spies, apprehended, searched and found to be carrying a copy of the 1605 set.[39] Nevertheless, Byrd felt safe enough to reissue both sets with new title pages in 1610

Psalms, songs and sonnets (1611)

[edit]Byrd's last collection of English songs was Psalms, Songs and Sonnets, published in 1611 (when Byrd was over 70) and dedicated to Francis Clifford, 4th Earl of Cumberland, who later also received the dedication of Thomas Campion's First Book of Songs in about 1613. The layout of the set broadly follows the pattern of Byrd's 1589 set, being laid out in sections for three, four, five and six parts like its predecessor and embracing an even wider miscellany of styles (perhaps reflecting the influence of another Jacobean publication, Michael East's Third Set of Books (1610)). Byrd's set includes two consort fantasias (a4 and a6) as well as eleven English motets, most of them setting prose texts from the Bible. These include some of his most famous compositions, notably Praise our Lord, all ye Gentiles (a6), This day Christ was born (a6) and Have mercy upon me (a6), which employs alternating phrases with verse and full scoring and was circulated as a church anthem. There are more carols set in verse and burden form as in the 1589 set as well as lighter three- and four-part songs in Byrd's "sonnets and pastorals" style. Some items are, however, more tinged with madrigalian influence than their counterparts in the earlier set, making clear that the short-lived madrigal vogue of the 1590s had not completely passed Byrd by. Many of the songs follow, and develop further, types already established in the 1589 collection.

Last works

[edit]

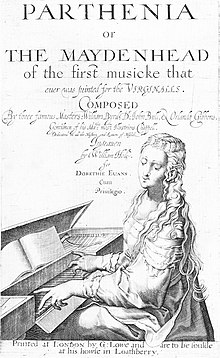

Byrd also contributed eight keyboard pieces to Parthenia (winter 1612–13), a collection of 21 keyboard pieces engraved by William Hole, and containing music by Byrd, John Bull and Orlando Gibbons. It was issued in celebration of the forthcoming marriage of James I's daughter Princess Elizabeth to Frederick V, Elector Palatine, which took place on 14 February 1613. The three composers are nicely differentiated by seniority, with Byrd, Bull and Gibbons represented respectively by eight, seven and six items. Byrd's contribution includes the famous Earle of Salisbury Pavan, composed in memory of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, who had died on 24 May 1612, and its two accompanying galliards. Byrd's last published compositions are four English anthems printed in Sir William Leighton's Teares or Lamentacions of a Sorrowfull Soule (1614).

Legacy

[edit]Byrd's output of about 470 compositions amply justifies his reputation as one of the great masters of European Renaissance music. Perhaps his most impressive achievement as a composer was his ability to transform so many of the main musical forms of his day and stamp them with his own identity. Having grown up in an age in which Latin polyphony was largely confined to liturgical items for the Sarum rite, he assimilated and mastered the Continental motet form of his day, employing a highly personal synthesis of English and continental models. He virtually created the Tudor consort and keyboard fantasia, having only the most primitive models to follow. He also raised the consort song, the church anthem and the Anglican service setting to new heights. Finally, despite a general aversion to the madrigal, he succeeded in cultivating secular vocal music in an impressive variety of forms in his three sets of 1588, 1589 and 1611.

Byrd enjoyed a high reputation among English musicians. As early as 1575 Richard Mulcaster and Ferdinand Haybourne praised Byrd, together with Tallis, in poems published in the Tallis/Byrd Cantiones. Despite the financial failure of the publication, some of his other collections sold well, while Elizabethan scribes such as the Oxford academic Robert Dow, Baldwin, and a school of scribes working for the Norfolk country gentleman Sir Edward Paston copied his music extensively. Dow included Latin distichs and quotations in praise of Byrd in his manuscript collection of music, the Dow Partbooks (GB Och 984–988), while Baldwin included a long doggerel poem in his Commonplace Book (GB Lbm Roy App 24 d 2) ranking Byrd at the head of the musicians of his day:

- Yet let not straingers bragg, nor they these soe commende,

- For they may now geve place and sett themselves behynde,

- An Englishman, by name, William BIRDE for his skill

- Which I shoulde heve sett first, for soe it was my will,

- Whose greater skill and knowledge dothe excelle all at this time

- And far to strange countries abrode his skill dothe shyne...[40]

In 1597 Byrd's pupil Thomas Morley dedicated his treatise A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke to Byrd in flattering terms, though he may have intended to counterbalance this in the main text by some sharply satirical references to a mysterious "Master Bold". In The Compleat Gentleman (1622) Henry Peacham (1576–1643) praised Byrd in lavish terms as a composer of sacred music:

- "For Motets and musick of piety and devotion, as well as for the honour of our Nation, as the merit of the man, I prefer above all our Phoenix M[aster] William Byrd, whom in that kind, I know not whether any may equall, I am sure none excel, even by the judgement of France and Italy, who are very sparing in the commendation of strangers, in regard of that conceipt they hold of themselves. His Cantiones Sacrae, as also his Gradualia, are mere Angelicall and Divine; and being of himself naturally disposed to Gravity and Piety, his vein is not so much for leight Madrigals or Canzonets, yet his Virginella and some others in his first Set, cannot be mended by the best Italian of them all."[41]

Finally, and most intriguingly, it has been suggested that a reference to "the bird of loudest lay" in Shakespeare's mysterious allegorical poem The Phoenix and the Turtle may be to the composer. The poem as a whole has been interpreted as an elegy for the Catholic martyr St Anne Line, who was executed at Tyburn on 27 February 1601 for harbouring priests.[42]

Byrd was an active and influential teacher. As well as Morley, his pupils included Peter Philips, Tomkins and probably Thomas Weelkes, the first two of whom were important contributors to the Elizabethan and Jacobean virginalist school. However, by the time Byrd died in 1623 the English musical landscape was undergoing profound changes. The principal virginalist composers died off in the 1620s (except for Giles Farnaby, who died in 1640, and Thomas Tomkins, who lived on until 1656) and found no real successors. Thomas Morley, Byrd's other major composing pupil, devoted himself to the cultivation of the madrigal, a form in which Byrd himself took little interest. The native tradition of Latin music which Byrd had done so much to keep alive more or less died with him, while consort music underwent a huge change of character at the hands of a brilliant new generation of professional musicians at the Jacobean and Caroline courts. The English Civil War, and the change of taste brought about by the Stuart Restoration, created a cultural hiatus which adversely affected the cultivation of Byrd's music together with that of Tudor composers in general.

In a small way, it was his Anglican church music which came closest to establishing a continuous tradition, at least in the sense that some of it continued to be performed in choral foundations after the Restoration and into the eighteenth century. Byrd's exceptionally long lifespan meant that he lived into an age in which many of the forms of vocal and instrumental music which he had made his own were beginning to lose their appeal to most musicians. Despite the efforts of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century antiquarians, the reversal of this judgement had to wait for the pioneering work of twentieth-century scholars from E. H. Fellowes onwards.

In more recent times, Joseph Kerman, Oliver Neighbour, Philip Brett, John Harley, Richard Turbet, Alan Brown, Kerry McCarthy, and others have made major contributions to increasing our understanding of Byrd's life and music. In 1999, Davitt Moroney's recording of Byrd's complete keyboard music was released on Hyperion (CDA66551/7; re-issued as CDS44461/7). This recording, which won the 2000 Gramophone Award in the Early Music category and a 2000 Jahrespreis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik, came with a 100-page essay by Moroney on Byrd's keyboard music. In 2010, The Cardinall's Musick, under the direction of Andrew Carwood, completed their recorded survey of Byrd's Latin church music. This series of thirteen recordings marks the first time that all of Byrd's Latin music has been available on disc.

Modern editions

[edit]- The Byrd Edition (gen. ed. P. Brett), Vols 1–17 (London, 1977–2004)

- A. Brown (ed.) William Byrd, Keyboard Music (Musica Britannica 27–28, London, 1971)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Byrd's father may have been recorded in the rolls of the Worshipful Company of Fletchers in London, and a person of the same name was buried on 12 November 1575 at the church of All Hallows Lombard Street (now demolished).[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "William Byrd". Gramophone Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Nagley & Milsom 2002, p. 386.

- ^ Harley 2016b, pp. 391–394.

- ^ a b Harley 2016a, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Kerman 2001, p. 714.

- ^ Harley 2016b, p. 14.

- ^ McCarthy 2013, p. 4.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Harley 2016a, p. 18.

- ^ a b Harley 2016a, p. 52.

- ^ Harley 2016a, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Monson 2008.

- ^ McCarthy 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Harley 2016b, ch.2.

- ^ Harley 2016b, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Harley 2016b, p. 38.

- ^ McCarthy 2013, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Walker 1952, p. 48.

- ^ Harley 2016b, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Neighbour 2007.

- ^ Harley 2016b, pp. 44–48

- ^ Harley 2016b, p. 74.

- ^ Kerman 1980, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Harley 2016b, ch.5.

- ^ Harley 2016b, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Harley 2016b, p. 126.

- ^ McCarthy 2013, p. 158.

- ^ Brett 2007, p. viii.

- ^ Walker 1952, p. 72.

- ^ Kerman 1980, pp. 85–87.

- ^ McCarthy 2004.

- ^ Kerman 1980, p. 35ff.

- ^ Kerman 1980, pp. 37–46.

- ^ Smith 2016.

- ^ Walker 1952, p. 77.

- ^ Grapes 2018.

- ^ Harley 2005.

- ^ Clulow 1966.

- ^ Harley 2016b, p. 142ff.

- ^ Boyd 1962, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Boyd 1962, p. 83.

- ^ Finnis, J.; Martin, P. (18 April 2003). "Another Turn for the Turtle: Shakespeare's Intercession for Love's Martyr". Times Literary Supplement. pp. 12–14.

Sources

[edit]- Boyd, Morrison Comegys (1962). Elizabethan Music and Musical Criticism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. OCLC 1156338180.

- Brett, Philip (2007). William Byrd and his Contemporaries: Essays and a Monograph. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-05202-4-758-1.

- Clulow, P. (1966). "Publication Dates for Byrd's Latin Masses". Music and Letters. 47: 1–9. doi:10.1093/ml/47.1.1.

- Grapes, K. Dawn (2018). With mornefull musique: funeral elegies in early modern England. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-17832-7-351-5.

- Harley, J. (2005). "My Lady Nevell Revealed". Music and Letters. 86: 1–15. doi:10.1093/ml/gci001. 191640785.

- Harley, John (2016a). The World of William Byrd: Musicians, Merchants and Magnates. Abingdon, UK; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-14094-0-088-2.

- Harley, John (2016b). William Byrd: Gentleman of the Chapel Royal. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-13515-3-694-3.

- Kerman, Joseph (1980). The Masses and Motets of William Byrd. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-05200-4-033-5.

- Kerman, Joseph (2001). "Byrd, William". In Sadie, Tyrrell; John, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-03336-0-800-5.

- McCarthy, Kerry (2004). "Byrd, Augustine and Tribue Domine". Early Music. 32 (4): 569–576. doi:10.1093/em/32.4.569. S2CID 192168961.

- McCarthy, Kerry (2013). Byrd. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01953-8-875-6.

- Monson, Craig (2008). "Byrd, William (1539x43–1623)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4267. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Nagley, Judith; Milsom, John (2002). "Dunstaple, John". In Latham, Alison (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01995-7-903-7.

- Neighbour, Oliver (2007). "Music Manuscripts of George Iliffe from Stanford Hall, Leicestershire, including a new ascription to Byrd". Music and Letters. 88 (3). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 420–435. doi:10.1093/ml/gcm007. ISSN 0027-4224. 192181960.

- Smith, Jeremy L. (2016). Verse and Voice in Byrd's Song Collections of 1588 and 1589. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-17832-7-082-8.

- Walker, Ernest (1952). Westrup, J.A. (ed.). A History of Music in England (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 3748254.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Alan; Turbet, Richard, eds. (1992). Byrd Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-05214-0-129-6.

- Neighbour, Oliver (1978). The Consort and Keyboard Music of William Byrd. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-05200-3-486-0.

- Turbet, Richard (1987). William Byrd: A Guide to Research. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-08240-8-388-5.

- Turbet, Richard (2012). William Byrd: A Research and Information Guide (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-02031-1-234-2.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to William Byrd at Wikiquote

Quotations related to William Byrd at Wikiquote Works related to William Byrd at Wikisource

Works related to William Byrd at Wikisource

- Free scores by William Byrd at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by William Byrd in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- List of compositions by William Byrd at the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (DIAMM) – a detailed alphabetical list

Recordings

[edit]- Free recordings of Madrigals, Latin Church Music

- Free recordings of Byrd's Ave verum corpus Archived 14 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Free recordings of Mass for four voices and some Christmas motets

- Motet Ave Verum Corpus as interactive hypermedia at the BinAural Collaborative Hypertext

- Kunst der Fuge: William Byrd – Free MIDI files

- William Byrd

- 16th-century births

- 1623 deaths

- English classical composers of church music

- English Roman Catholics

- Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal

- Composers for harpsichord

- English Renaissance composers

- 16th-century English composers

- 17th-century English composers

- 16th-century English musicians

- 17th-century English musicians

- Composers from London

- English male classical composers

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism

- Burials in Essex

- 17th-century English male musicians