History of Easter Island

Geologically one of the youngest inhabited territories on Earth, Easter Island (also called Rapa Nui), located in the mid-Pacific Ocean, was, for most of its history, one of the most isolated. Its inhabitants, the Rapa Nui, have endured famines, epidemics of disease, civil war, environmental collapse, slave raids, various colonial contacts,[1][2] and have seen their population crash on more than one occasion. The ensuing cultural legacy has brought the island notoriety out of proportion to the number of its inhabitants.

First settlers

[edit]Early European visitors to Easter Island recorded the local oral traditions about the original settlers. In these traditions, Easter Islanders claimed that a chief Hotu Matu'a[3] arrived on the island in one or two large canoes with his wife and extended family.[4] They are believed to have been Polynesian. There is considerable uncertainty about the accuracy of this legend as well as the date of settlement. Published literature suggests the island was settled around 300–400 CE. Some scientists say that Easter Island was not inhabited until 700–800 CE. This date range is based on glottochronological calculations and on three radiocarbon dates from charcoal that appears to have been produced during forest clearance activities.[5] Moreover, a recent study which included radiocarbon dates from what is thought to be very early material suggests that the island was settled as recently as 1200 CE.[6] This seems to be supported by a 2006 study of the island's deforestation, which may have started around the same time.[7][8] A large now extinct palm, Paschalococos disperta, related to the Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis), was one of the dominant trees as attested by fossil evidence; this species, whose sole occurrence was Easter Island, became extinct.[9]

The Austronesian Polynesians, who first settled the island, are likely to have arrived from the Marquesas Islands from the west. These settlers brought bananas, taro, sugarcane, and paper mulberry, as well as chickens and Polynesian rats. The island at one time supported a relatively advanced and complex civilization.

It is suggested that the reason settlers sought an isolated island was because of high levels of Ciguatera fish poisoning in their then-current surrounding area.[10]

South American links

[edit]

The Norwegian botanist and explorer Thor Heyerdahl (and many others) has documented that cultural similarities exist between Easter Island and South American Indian cultures. He has suggested that this most likely came from some settlers arriving from the continent.[11] According to local legends, a group of people called hanau epe (meaning either "long eared" or "stocky" people) came into conflict with another group called the hanau momoko (either "short-eared" or "slim" people).[12] After mutual suspicions erupted in a violent clash, the hanau epe were overthrown and nearly exterminated, leaving only one survivor.[13] Various interpretations of this story have been made – that it represents a struggle between natives and incoming migrants; that it recalls inter-clan warfare; or that represents a class conflict.[14]

Despite these claims, DNA sequence analysis of Easter Island's current inhabitants indicates that the 36 people living on Rapa Nui who survived the devastating internecine wars, slave raids and epidemics of the 19th century and had any offspring,[15] were Polynesian. Furthermore, examination of skeletons offers evidence of only Polynesian origins for Rapa Nui living on the island after 1680.[16]

Pre-European society

[edit]

According to legends recorded by the missionaries in the 1860s, the island originally had a very clear class system, with an ariki, king, wielding absolute god-like power ever since Hotu Matua had arrived on the island. The most visible element in the culture was production of massive moai that were part of the ancestral worship. With a strictly unified appearance, moai were erected along most of the coastline, indicating a homogeneous culture and centralized governance. In addition to the royal family, the island's habitation consisted of priests, soldiers and commoners.

The ariki mau, Kai Mako'i 'Iti, along with his grandson Mau Rata, died in the 1860s while serving as an indentured servant in Peru.[17]

For unknown reasons, a coup by military leaders called matatoa had brought a new cult based around a previously unexceptional god, Make-make. In the cult of the birdman (Rapa Nui: tangata manu), a competition was established in which every year a representative of each clan, chosen by the leaders, would swim across shark-infested waters to Motu Nui, a nearby islet, to search for the season's first egg laid by a manutara (sooty tern). The first swimmer to return with an egg and successfully climb back up the cliff to Orongo would be named "Birdman of the year" and secure control over distribution of the island's resources for his clan for the year. The tradition was still in existence at the time of first contact by Europeans but was suppressed by Christian missionaries in the 1860s.

The "statue-toppling"

[edit]European accounts in 1722 (Dutch) and 1770 (Spanish) reported seeing only standing statues, which were still venerated, but by James Cook's visit in 1774 many were reported toppled. The huri mo'ai – the "statue-toppling" – continued into the 1830s. By 1838, the only standing moai were on the slopes of Rano Raraku and Hoa Hakananai'a at Orongo. In about 60 years, islanders had damaged this part of their ancestors' heritage;[18] theories have ranged from intertribal warfare to loss of faith in their ancestors' ability to protect them. In modern times, moai have been restored at Anakena, Ahu Tongariki, Ahu Akivi and Hanga Roa.

European contacts

[edit]

The first-recorded European contact with the island took place on 5 April (Easter Sunday) 1722 when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen[21] visited for a week and estimated there were 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants on the island. His party reported "remarkable, tall, stone figures, a good 30 feet in height", the island had rich soil and a good climate and "all the country was under cultivation". Fossil-pollen analysis shows that the main trees on the island had gone 72 years earlier in 1650[citation needed].

The islanders were fascinated by the Dutch and sailed out to meet them, unarmed. The Dutch officer, Karl Friedrich Barons, wrote of the encounter[citation needed]:

During the morning [the captain] brought an Easter Islander onboard with his craft. This hapless creature seemed to be very glad to behold us, and he showed the greatest wonder at the build of our ship. He took special notice of the taughtness of our spars, the stoutness of our rigging and running gear, the sails, the guns, which he felt all over with minute attention and with everything else that he saw. When the image of his own features was displayed before him in a mirror, he started suddenly back, and then looked toward the back of the glass, apparently in the expectation of discovering the cause of the apparition. After we had sufficiently beguilded ourselves with him and he with us, we started him off again in his canoe towards the shore

When the Dutch got to shore, the islanders pressed around them, tried to touch the Dutch, their clothes, and even their guns. During this, a shot rang out from an unknown person, leading to a firefight that killed ten or twelve islanders. To their distress, they learned that among them was the young man who they had shown their ship, to which Barons stated that the crew was "much grieved". The natives soon returned – not for revenge, but seeking to trade food for the bodies of their fallen. The Dutch left shortly thereafter[citation needed].

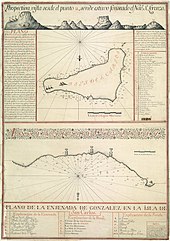

The next foreign visitors arrived on 15 November 1770: two Spanish ships, San Lorenzo and Santa Rosalia, sent by the Viceroy of Peru, Manuel de Amat, and commanded by Felipe González de Ahedo. They spent five days on the island, performing a very thorough survey of its coast, and named it Isla de San Carlos, taking possession on behalf of King Charles III of Spain, and ceremoniously erected three wooden crosses on top of three small hills on Poike.[22]

Four years later, in mid-March 1774, British explorer James Cook visited Easter Island. Cook himself was too sick to walk far, but a small group explored the island.[23] They reported the statues as being neglected with some having fallen down; no sign of the three crosses and his botanist described it as "a poor land". He had a Tahitian interpreter who could partially understand the language.[23] Other than in counting, though, the language was unintelligible.[24] Cook later estimated that there were about 700 people on the island. He saw only three or four canoes, all unseaworthy. Parts of the island were cultivated with banana, sugarcane, and sweet potatoes, while other parts looked like they had once been cultivated but had fallen into disuse. Georg Forster reported in his account that he saw no trees over ten feet tall on the island.[25] Cook also noted that, unlike before, the islanders carried weapons when approaching foreign visitors – "spears, six or eight feet long, which are pointed at one end with pieces of black flint".

On 10 April 1786, the French explorer Jean François de Galaup La Pérouse visited and made a detailed map of Easter Island.[26] He described the island as one-tenth cultivated and estimated that the population of the island was around two thousand.[27] As published maps increasingly included the island, by the 19th century it had become a common resupply stop for sealing and whaling ships, with over fifty known visits. Over time, these stops (starting with an 1805 visit from an American sealing ship) increasingly included pressing the islanders into the ships' crews as forced labourers, and – ultimately – outright slave raids.

Destruction of society and population

[edit]A series of devastating events killed almost the entire population of Easter Island. Jared Diamond suggested that Easter Island's society so destroyed their environment that, by around 1600, their society fell into a downward spiral of warfare, cannibalism, and population decline (see ecocide hypothesis). Critics contend that society was largely peaceful and booming at the time of western contact and that it only went into a catastrophic decline after the introduction of western diseases and slaving raids (see criticism of the ecocide theory).

Disaster arrived in the 1860s when Peruvian slavers came, looking for captives to sell in Peru. Easter Island was not the only island to suffer but it was the hardest hit because it was closest to the South American coast. Eight ships arrived to Easter Island in December 1862. About 80 seamen assembled on the beach while trade goods such as necklaces, mirrors and other items were spread out. At a signal, guns were fired and islanders were caught, tied up, and carried off to the ships. At least ten Rapanui were killed. A second and third landing was attempted in the following days, but defensive measures forced a retreat back to the ships. More than 1400 Rapanui islanders were kidnapped. Some were sold in Peru as domestic servants; others for manual labor on the plantations. Food was inadequate and discipline harsh; medical care was virtually non-existent. Islanders sickened and died. As word of the activities of the slavers spread, public opinion in Peru became hostile to this trade in human beings. Newspapers wrote angry editorials and the French Government and missionary societies protested. Convinced that the entire "immigration scheme" was damaging the reputation of Peru in the eyes of the rest of the world, the Peruvian Government announced that they would henceforth "prohibit the introduction of Polynesian settlers".[28]

In December 1862, Peruvian slave raiders struck Easter Island. Violent abductions continued for several months, eventually capturing or killing around 1500 men and women, about half of the island's population. International protests erupted, escalated by Bishop Florentin-Étienne Jaussen of Tahiti. The slaves were finally freed in autumn 1863, but by then most of them had already died of tuberculosis, smallpox and dysentery. Finally, a dozen islanders managed to return from the horrors of Peru, but brought with them smallpox and started an epidemic, which reduced the island's population to the point where some of the dead were not even buried.[29]

The first Christian missionary, Eugène Eyraud, arrived in January 1864 and spent most of that year on the island and reported for the first time the existence of the so-called rongo-rongo tablets; but mass conversion of the Rapa Nui only came after his return in 1866 with Father Hippolyte Roussel. Two other missionaries arrived with Captain Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier. Eyraud contracted tuberculosis during the 1867 island epidemic, which took a quarter of the island's remaining population of 1,200, with only 930 Rapanui remaining. The dead included the last ariki mau, the last East Polynesia royal first-born son, the 13-year-old Manu Rangi. Eyraud died of tuberculosis in August 1868, by which time almost the entire Rapa Nui population had become Roman Catholic.[30]

The Huntwell was wrecked in February 1871, leaving twelve men stranded on the island. The Indiaman sank off Easter on March 19, 1872, stranding some 30 persons on the island. It was two months before they were picked up by another ship. In 1892, when the Clorinda foundered off the island, survivors were stranded for three months.[31]

Dutrou-Bornier

[edit]Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier – who had served as an artillery officer in the Crimean War, but was later arrested in Peru, accused of arms dealing and sentenced to death, to be released after intervention from the French consul – first came to Easter Island in 1866 when he transported two missionaries there, returned in 1867 to recruit laborers for coconut plantations, and then came again to stay in April 1868, burning the yacht he had arrived in. He was to have a long-lasting impact on the island.

Dutrou-Bornier set up residence at Mataveri, aiming to cleanse the island of most of the Rapa Nui and turn it into a sheep ranch. He married Koreto, a Rapa Nui, and appointed her Queen, tried to persuade France to make the island a protectorate, and recruited a faction of Rapa Nui whom he allowed to abandon their Christianity and revert to their previous faith. With rifles, a cannon, and hut burning supporters, he ran the island for several years.[32][page needed]

Dutrou-Bornier bought up all of the island apart from the missionaries' area around Hanga Roa and moved a couple hundred Rapa Nui to Tahiti to work for his backers. In 1871 the missionaries, having fallen out with Dutrou-Bornier, evacuated 275 Rapa Nui to Mangareva and Tahiti, leaving only 230 on the island.[33][34] Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, there were just 111 people living on Easter Island.[15]

In 1876, Dutrou-Bornier was murdered in an argument over a dress, though his kidnapping of pubescent girls may also have motivated his killers.[35]

Neither his first wife back in France, who was heir under French law, nor his second wife on the island, who briefly installed their daughter Caroline as Queen, were to keep much from his estate. But to this day much of the island is a ranch controlled from off-island and for more than a century real power on the island was usually exercised by resident non-Rapa Nui living at Mataveri. An unusual number of shipwrecks had left the island better supplied with wood than for many generations, whilst legal wrangles over Dutrou-Bornier's land deals were to complicate the island's history for decades to come.[32][page needed]

1878–1888

[edit]Alexander Salmon Jr., was the brother of the Queen of Tahiti, the son of an English merchant adventurer, and a member of the mercantile dynasty that had bankrolled Dutrou-Bornier. He arrived on the island in 1878 with some fellow Tahitians and returning Rapa Nui and ran the island for a decade. As well as producing wool he encouraged the manufacture of Rapa Nui artworks, a trade that thrives to this day. It was this era of peace and recovery that saw the linguistic change from old Rapa Nui to the Tahitian-influenced modern Rapa Nui language, and some changes to the island's myths and culture to accommodate other Polynesian and Christian influences (notably, Ure, the old Rapa Nui word for "penis", was dropped from many people's names).[36]

This era saw archaeological and ethnographic studies, one in 1882 by the Germans on the gunboat SMS Hyäne, and again in 1886 by the American sloop USS Mohican, whose crew excavated Ahu Vinapu with dynamite.[37]

Father Roussel made a number of pastoral visits in the decade, but the only permanent representatives of the church were Rapa Nui catechists including, from 1884, Angata, one of the Rapa Nui who had left with the missionaries in 1871. Despite the lack of a resident priest to celebrate mass regularly, the Rapa Nui had returned to Roman Catholicism, but there remained some tension between temporal and spiritual power as Father Roussel disapproved of Salmon because of his Jewish paternity.[38]

Incorporation to Chile

[edit]In 1776 the Chilean priest Juan Ignacio Molina highlights the island for its "monumental statues" in the fifth chapter on "Chilean Islands" of his book "Natural and Civil History of the Kingdom of Chile".[39]

On 8 March 1837, under the command of Teniente de Marina Leoncio Señoret, the ship of the Chilean Navy Colo Colo sailed off from Valparaíso bound for Australia.[40] Thus, the Colo Colo was the first Chilean ship to visit the Easter Island.

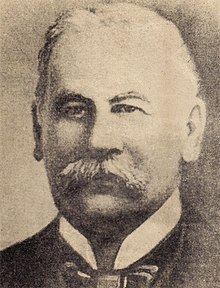

A professional sailor, in 1870 Policarpo Toro Hurtado arrived with the corvette "O'Higgins" to Easter Island or Rapa Nui, being amazed by the culture and history of its long-suffering people whose culture had been on the verge of disappearing at the mercy of corsairs, slave hunters and internal conflicts, which had reduced its population at some point to only a little more than 100 people.

Immediately, Toro Hurtado began to worry about the fate of this abandoned island in the Pacific, stricken by piracy, slave smuggling and misery. He then had the idea that it could be definitively within the Chilean territorial limits, which some considered delirious, especially because France had included it among its Polynesian possessions since 1822, although it was owned by private hands. In the same year of 1870, Chile had sent a commission to investigate the island, under the command of Captain Luis Ignacio Gana, although without the objective of studying a possible annexation to the country.

In 1887 Chile took concrete actions to incorporate the island into the national territory, at the request of the Chilean Navy Captain Policarpo Toro, who was concerned about the unprotected situation of the Rapa Nui for decades and began to influence the situation on his own initiative. Policarpo, through negotiations, bought land on the island at the request of the Bishop of Valparaiso, Salvador Donoso Rodriguez, owner of 600 hectares, together with the Salmon brothers, Dutrou-Bornier and John Brander, from Tahiti. The Chilean captain put money from his own pocket for this purpose, together with 6000 pounds sterling sent by the Chilean government.[39] According to Rapa Nui tradition, the lands could not be sold, however, third parties believed they owned them and they were bought from them so that they would not interfere in the affairs of the island from that moment on.

At that time, the Rapa Nui population reached alarming numbers. In a census carried out by the Chilean corvette Abtao in 1892, there were only 101 Rapa Nui alive, of which only 12 were adult men. The Rapa Nui ethnic group, along with their culture, was at its closest point to extinction.[39]

Then, on September 9, 1888, thanks to the efforts of the Bishop of Tahiti, Monsignor José María Verdier, the Agreement of Wills (Acuerdo de Voluntades) was signed, in which the local representative Atamu Tekena, head of the Council of Rapanui Chiefs ceded the sovereignty of the island to the State of Chile, represented by Policarpo Toro. The Rapa Nui elders ceded sovereignty, without renouncing their titles as chiefs, the ownership of their lands, the validity of their culture and traditions and on equal terms. The Rapa Nui sold nothing, they were integrated in equal conditions to Chile.

The annexation to Chile, together with the abolition of slavery in Peru, brought the advantage that foreign slavers did not take any more inhabitants from the island. However, in 1895, the Compañía Explotadora de Isla de Pascua from Enrique Merlet obtained the concession of the entire island after the failure of the State's colonization plan following the Civil War of 1891 and the change of government in the country.

The company imposed prohibitions to live and work outside Hanga Roa and even forced labor of the islanders in the company, something that was avoided thanks to the "safe-conducts" given by the Navy that allowed the islanders to cross the entire island once the Navy took control of the island during the 20th Century.[41]

In 1903 the island was bought by the English sheep-farming company Williamson Balfor from the Merlet company, and – no longer being able to farm for food – the natives were forced to work on the ranches in order to buy food.[42]

20th century

[edit]

The Mana Expedition led by Katherine and William Scoresby Routledge landed on the island in March 1914, conducting a 17-month archaeological and ethnographic survey.[43] In October of the same year, the German East Asia Squadron including the Scharnhorst, Dresden, Leipzig and Gneisenau assembled off the island at Hanga Roa before sailing on to Coronel and the Falklands.[44] Another German warship, the commerce raider Prinz Eitel Friedrich, visited in December and released 48 British and French merchant seamen onto the island, supplying much needed labour for the archaeologists expedition.[45]

In 1914 there was an uprising of the natives inspired by the elderly catechist María Angata Veri Veri and led by Daniel Maria Teave with the aim of getting the State to take charge of the situation generated by the company. The Navy held the company responsible for the "brutal and savage acts" committed by Merlet and the company's administrators and an investigation was requested.

In 1916, the island was declared a subdelegation of the Department of Valparaíso. In the same year, Archbishop Rafael Edwards Salas visited the island and became the main spokesman for the natives' complaints and demands. However, the Chilean State decided to renew the lease to the Company, under the figure of the so-called "Provisional Temperament", distributing additional lands to the natives (5 ha per marriage as of 1926), allocating lands for the Chilean administration and establishing the permanent presence of the Navy, which in 1936 established a regulation according to which, with prior permission, the natives could leave Hanga Roa to fish or provide themselves with fuel.[41][46]

Monsignor Rafael Edwards sought to have the island declared a "naval jurisdiction" in order to intervene in it as military vicar and in this way support the Rapa Nui community, creating better living conditions.[41]

In 1933, the Chilean State Defense Council required the registration of the island in the name of the State in order to protect it from private individuals who wanted to register it in their own name.[41]

Until the 1960s the Rapanui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the Williamson-Balfour Company as a sheep farm until 1953 when President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo cancelled the company's contract for non-compliance and then assigned the entire administration of the island to the Chilean Navy.[47] The island was then managed by the Chilean Navy until 1966, at which point the island was reopened in its entirety. The Rapanui were given Chilean citizenship that year with the Pascua Law enacted during the government of Eduardo Frei Montalva.[48] Only Spanish was taught in the schools until that year. The Law also created the Isla de Pascua commune depending from the Valparaíso Province and implemented the Civil Registry, created the positions of governor, mayor and councilman, as well as the 6th Police Station of Carabineros de Chile, the first fire company of Easter Island, schools and a hospital. The first mayor was sworn in 1966 and was Alfonso Rapu who sent a letter to President Frei two years prior influencing him to create the Pascua Law.

Islanders were only able to travel off the island easily after the construction of the Mataveri International Airport in 1965, which was built by the Longhi construction company, carrying hundreds of workers, heavy machinery, tents and a field hospital on ships. However, its use did not go beyond airline operations with small groups of tourists. At the same time, a NASA tracking station operated on the island, which ceased operations in 1975.

Between 1965 and 1970, the United States Air Force (USAF) settled on Easter Island, radically changing the way of life of the Rapa Nui, as they became acquainted with the customs of the consumer societies of the developed world.[49][50]

In April 1967 LAN Chile flights began to land and the island began to be oriented towards cultural tourism. Since then, the main concerns for the natives were to strengthen production and marketing cooperatives, which received state support, and to recover their communal lands.

Following the 1973 Chilean coup d'état that brought Augusto Pinochet to power, Easter Island was placed under martial law. Tourism slowed down and private property was restored. During his time in power, Pinochet visited Easter Island on three occasions. The military built a number of new military facilities and a new city hall.[51]

On January 24, 1975, television arrived on the island, with the inauguration of a station of Televisión Nacional de Chile, which broadcast programming on a delayed basis until 1996, when live satellite transmissions to the island began.

In 1976 the Isla de Pascua Province was created with Arnt Arentsen Pettersen appointed as the first governor between 1976 and 1979. Between 1984 and 1990 the administration of Governor Sergio Rapu Haoa stands out and since then all the governors have been Rapanui.

In 1979, Decree Law No. 2885 was enacted to grant individual land titles to regular holders.

On April 1, 1986, Law No. 18,502 is enacted, which establishes the special fuel subsidy in Easter Island, stating that it "may not exceed in each product 3.5 monthly tax units per cubic meter, whose value may be paid directly or through the imputation of the respective amount to the payment of certain taxes".

As a result of an agreement in 1985 between Chile and the United States, the runway at Mataveri International Airport was extended by 423 metres (1,388 ft), reaching 3,353 metres (11,001 ft), and was re-opened in 1987. Pinochet is reported to have refused to attend the opening ceremony in protest against pressures from the United States to address human rights cases.[52]

21st century

[edit]On 30 July 2007, a constitutional reform gave Easter Island and the Juan Fernández Islands (also known as Robinson Crusoe Island) the status of "special territories" of Chile. Pending the enactment of a special charter, the island continued to be governed as a province of the V Region of Valparaíso.[53]

A total solar eclipse visible from Easter Island occurred for the first time in over 1300 years on 11 July 2010, at 18:15:15.[54]

Species of fish were collected in Easter Island for one month in different habitats including shallow lava pools, depths of 43 meters, and deep waters. Within these habitats, two holotypes and paratypes, Antennarius randalli and Antennarius moai, were discovered. These are considered frog-fish because of their characteristics: "12 dorsal rays, last two or three branched; bony part of first dorsal spine slightly shorter than second dorsal spine; body without bold zebra-like markings; caudal peduncle short, but distinct; last pelvic ray divided; pectoral rays 11 or 12".[55]

Indigenous rights movement

[edit]Starting in August 2010, members of the indigenous Hitorangi clan occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa.[56][57] The occupiers allege that the hotel was bought from the Pinochet government, in violation of a Chilean agreement with the indigenous Rapa Nui, in the 1990s.[58] The occupiers say their ancestors had been cheated into giving up the land.[59] According to a BBC report, on 3 December 2010, at least 25 people were injured when Chilean police using pellet guns attempted to evict from these buildings a group of Rapa Nui who had claimed that the land the buildings stood on had been illegally taken from their ancestors.[60]

In January 2011, the UN's Special Rapporteur on Indigenous People, James Anaya, expressed concern about the treatment of the indigenous Rapa Nui by the Chilean government, urging Chile to "make every effort to conduct a dialogue in good faith with representatives of the Rapa Nui people to solve, as soon as possible the real underlying problems that explain the current situation".[56] The incident ended in February 2011, when up to 50 armed police broke into the hotel to remove the final five occupiers. They were arrested by the government and no injuries were reported.[56] Since being given Chilean citizenship in 1966, the Rapa Nui have re-embraced their ancient culture, or what could be reconstructed of it.[48]

Mataveri International Airport is the island's only airport. In the 1980s, its runway was lengthened by the U.S. space program to 3,318 m (10,885 ft) so that it could serve as an emergency landing site for the Space Shuttle. This enabled regular wide body jet services and a consequent increase of tourism on the island, coupled with migration of people from mainland Chile which threatens to alter the Polynesian identity of the island. Land disputes have created political tensions since the 1980s, with part of the native Rapa Nui opposed to private property and in favor of traditional communal property.

On 26 March 2015, local minority group Rapa Nui Parliament took control over large parts of the island, throwing out the CONAF park rangers in a non-violent revolution.[61] Their main goal is to obtain independence from Chile. The situation has not yet been resolved.

History of Science of Easter Island

[edit]Easter Island's long isolation was ended on Easter Sunday, 1722, when a Dutch explorer, Jacob Roggeveen, discovered the island. He named it for the Holy day. The Dutch were amazed by the great statues, which they thought were made from clay.[62][63]

A Spanish Captain, Don Felipe Gonzales, was the next to land at Easter Island, in 1770. He claimed the island for the King of Spain. The famed English explorer, Captain James Cook, stopped briefly in 1774, and a French admiral and explorer, La Perouse, spent 11 hours on the island in 1786. These early visitors spent little actual time on the island. They were searching for water, wood, and food but the island had few of these items and it also lacked a safe anchorage. They soon sailed onward. None of the early visitors saw the famous quarry where the statues were carved. Some noted that the land seemed well-cultivated, with fields neatly laid out. Comments were made of the unusual boat-shaped houses, and nearly all mentioned the lack of serviceable canoes.[64]

An ethnologist, Alfred Metraux, came to Easter Island as part of the Franco-Belgian Expedition (1934–35). Accompanied by Henri Lavachery, an archaeologist, Metraux gathered legends, traditions, and myths along with information on the material culture; his work has become a standard reference for the island's past. Metraux's books resulted in focusing the world's attention on the island (See Ethnology of Easter Island, 1971).[65][66]

History of archaeology

[edit]Major archaeological expeditions and studies on Easter Island: excavations, restorations, inventories and extended survey. In 1884, Geiseler conducted an archaeological inventory on Easter Island. In 1889, W. J. Thomson carried out an archaeological survey of the island's remains.

During 1914-1915, Mrs. Katherine Routledge undertook subsurface archaeological investigations, focusing on the statue bases at Rano Raraku. Her work also included excavations and explorations on Motu Nui, where she discovered the stone statue "Te titaahanga o te henua." During 1934-1935, Henri Lavachery and Alfred Métraux recorded petroglyphs, made surface observations of monuments, explored caves on Motu Nui, documented rock art, and studied human burials. Their comprehensive archaeological ethnology of Metraux contributed significantly to the island's understanding.

In 1935, the Ministry of Lands and Colonization declared Easter Island a National Park and a Historic Monument. In 1936, Cornejo and Atan conducted an archaeological inventory on Easter Island, further enriching the knowledge of the island's cultural history. In 1948, Father Sebastian Englert conducted archaeological studies on Easter Island. His research provided additional information on caves on Motu Nui and associated an anthropomorphic face with a warrior named Ure a Rei. His work encompassed various aspects, including archaeology, ethnology, history, and linguistics.

In 1955-1956, Thor Heyerdahl led a Norwegian expedition to Easter Island with six archaeologists. The expedition aimed to investigate various monuments on the island, shedding light on its prehistoric past and cultural significance. In 1958, Thomas Bartel conducted linguistic studies and translated Rongo Rongo tablets, alongside investigations of archaeological sites. His research contributed to our understanding of the island's unique script and its historical context. In 1960, Gonzalo Figueroa and William Mulloy led investigations and restoration efforts at Ahu Akivi, including the re-erection of statues.

In 1965, William Mulloy conducted measurements of azimuths of approximately 300 ahu facades for stellar orientation, contributing to our understanding of the island's ancient astronomical practices. In 1966, Mulloy and Figueroa published "The Archaeological Heritage of Easter Island," offering an extensive overview of the island's archaeological treasures. In 1968, an extensive archaeological inventory led by Mulloy, McCoy, Ayres, and Chilean Government and International Fund for Monuments surveyed Rano Kau and its environs (Quadrangles 1, 2, 4, 5, 6). The expedition involved survey and excavation, restoration of ahu and statues, and the documentation of caves and shelters. This comprehensive research led to the discovery of obsidian flakes and red earthen pigment.

During 1969-1976, Mulloy and Ayres focused on reconstruction techniques of carving, transporting, and erecting statues. Their work encompassed various ahu excavation and restoration projects, contributing to the island's preservation. In 1973, P. C. McCoy conducted the excavation of a rectangular house on the east rim of Rano Kau volcano, providing insights into the island's ancient architecture. In 1975, William Mulloy led investigations and restoration efforts in the southern half of the ceremonial center, focusing on masonry conservation and preservation of stone structures. This research also included historical context and recommendations for future work and visitor access. Additionally, the excavation and restoration of the solstice-oriented Ahu Vai Puku took place during this period.

During 1976-1993, Claudio Cristino F., Patricia Vargas C., and other researchers conducted an island-wide archaeological survey, adding to the understanding of Easter Island's rich history. In 1978, Patrick C. McCoy explored the significance of near-shore islets in Easter Island's prehistory. The research also examined the various roles of motu, including their use as retreats and fishing grounds. Excavations on Motu Nui and Motu Iti contributed to the island's historical knowledge. In 1979, W. S. Ayres led the excavation and restoration of the Ahu A Kivi-Vai Teka complex. The research included the description of construction stages and the site's destruction. In 1984, a team led by Christopher M. Stevenson, Leslie C. Shaw, and Claudio Cristino conducted a study of the Orito obsidian quarry. Their research focused on lithic reduction techniques, temporal aspects of obsidian use, and patterns of obsidian consumption at habitation sites. Extensive fieldwork and excavation activities were carried out in 1981.

In 1985, Joiko Henriquez conducted a study on the primitive paintings of Easter Island. The research encompassed bibliographic sources, critical history, conservation problems, and restoration proposals based on on-site observations conducted in October 1983. In 1985, Douglas W. Owsley and Ann-Marie Miles conducted a study on dental caries in the permanent teeth of prehistoric Easter Islanders. This research provided insights into dietary habits, oral health, and land tenure matters. The analysis of dental data was carried out with various support.

During 1986-1988, Sergio Rapu H., Sonia Haoa, Gill and Owlsley, and other researchers conducted osteological excavations at Ahu Naunau. During 1986-1988, the Kon-Tiki Museum team conducted test excavations. In December 1990, an archaeological survey was conducted in quadrangles 30 and 31, specifically in the La Perouse area. University of Chile and CONADIP: Prospection archaeological studies on Easter Island have been ongoing since 1977. These studies aim to explore the island's archaeological treasures and uncover its hidden history.[67][68][69][70]

In 2011, prehistoric pits—filled with red pigment that dated to between 1200 and 1650 CE, after the deforestation—were discovered by archaeologists. The pits contained red ochre consisting of the iron oxides hematite and maghemite and were covered with a lid.[71][72]

”This indicates, that even though the palm vegetation had disappeared, the prehistoric population of Easter Island continued the pigment production, and on a substantial scale" said archaeobotanist Welmoed Out from Moesgaard Museum.[73]

References

[edit]- ^ Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond

- ^ Diamond (2005), pp. 79–119.

- ^ Resemblance of the name to an early Mangarevan founder god Atu Motua ("Father Lord") has made some historians suspect that Hotu Matua was added to Easter Island mythology only in the 1860s, along with adopting the Mangarevan language. The "real" founder would have been Tu'u ko Iho, who became just a supporting character in Hotu Matu'a centric legends. See Steven Fischer (1994). Rapanui's Tu'u ko Iho Versus Mangareva's 'Atu Motua. Evidence for Multiple Reanalysis and Replacement in Rapanui Settlement Traditions, Easter Island. The Journal of Pacific History, 29(1), 3–18. See also Rapa Nui / Geography, History and Religion. Peter H. Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, University of Chicago Press, 1938. pp. 228–36. Online version.

- ^ Summary of Thomas S. Barthel's version of Hotu Matu'a's arrival to Easter Island.

- ^ Diamond (2005), p. 89.

- ^ Hunt, T. L., Lipo, C. P., 2006. Science, 1121879. See also "Late Colonization of Easter Island" in Science Magazine. Entire article Archived 2008-08-29 at the Wayback Machine is also hosted by the Department of Anthropology of the University of Hawaii.

- ^ Hunt, Terry L. (2006). "Rethinking the Fall of Easter Island". American Scientist. 94 (5 - September/October): 412–9. JSTOR 27858833. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Hunt, Terry; Lipo, Carl (2011). The Statues that Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-5031-3.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Chilean Wine Palm: Jubaea chilensis, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg Archived 2012-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Did fish poisoning drive Polynesian colonization of the Pacific?". 2009-07-07. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Heyderdahl, Thor. Easter Island – The Mystery Solved. Random House New York 1989.

- ^ Sebastian Englert's Rapa Nui dictionary with original Spanish translated to English.

- ^ The "Hanau Eepe", their Immigration and Extermination.

- ^ John Flenley, Paul G. Bahn, The Enigmas of Easter Island: Island on the Edge, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 76, 154.

- ^ a b "Rapa Nui – Untergang einer einmaligen Kultur". Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. 1994. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 104464 skeletons – definitely Polynesian

- ^ Fischer (2005), pp. 81, 89.

- ^ Fischer (2005), p. 64.

- ^ "Plano de la Ya. De Sn. Carlos descubierta por Dn. Phelipe Gonzalez de Haedo, Capitan de Fragta. Y Comte. Del Navio. De S.M. Nombrado Sn. Lorenzo y Frgta. Sta. Rosalia, acuya expedición salio del Puerto del Callao de Lima el dia 10 de octubre del año de 1770 ... : Esta situada esta ya. En 27 GRS. 6 ms. De lattd. S. Y en los 264 gs. 36 ms. De longd. Segun el meridno. De Thenerife" [Map of the Isle of San Carlos discovered by Don Felipe Gonzalez de Haedo... on 10 October 1770...]. Library of Congress (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "The Daulton Collection".

- ^ Salmond, Anne (2010). Aphrodite's Island. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0520261143.

- ^ Jo Anne Van Tilburg. Easter Island, Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. British Museum Press, London, 1994. ISBN 0-7141-2504-0

- ^ a b Pelta (2001), pp. 25-6.

- ^ Cook, James (1777). A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World. Vol. 1. Book 2, Chapters 7–8. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ Pelta (2001), pp. 27–8.

- ^ Pelta (2001), pp. 28–9.

- ^ Furgeson, Thomas; Gill, George W (2016). Stefan, Vincent H; Gill, George W (eds.). Skeletal Biology of the Ancient Rapanui (Easter Islanders). Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-107-02366-6. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Emory, Kenneth P. (April 1963). "Archaeology of Easter Island: Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific". American Antiquity (Review). 28 (4): 565–567. doi:10.2307/278580. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 278580.

- ^ Fischer (2005), pp. 86–91.

- ^ Fischer (2005), pp. 92–103.

- ^ McCall, Grant (1994). Rapanui: tradition and survival on Easter Island. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1641-2. OCLC 924758424.

- ^ a b Fischer (2005).

- ^ Fischer (2005), p. 113.

- ^ Routledge (1919) p. 208 put the number remaining on the island at 171.

- ^ Fischer (2005), p. 120.

- ^ Fischer (2005), pp. 123–31.

- ^ Fischer (2005), pp. 127, 131.

- ^ Fischer (2005), p. 124.

- ^ a b c Corporación Defensa de la Soberanía (2010). "Historia de la Isla de Pascua: Su incorporación y su conflicto con la Williamson & Balfour. Daños patrimoniales, pretensiones internacionales e independentismos". issuu.

- ^ Marcos Moncada Astudillo in La tradición naval respecto del primer buque chileno en Isla de Pascua, retrieved on 5 January 2013

- ^ a b c d e Marcos Moncada Astudillo (2002). "Monseñor Rafael Edwards Salas. Isla de Pascua y la Armada Nacional" (PDF) (in Spanish). Revista Marina. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Marisol Hitorangi (18 June 2023). "Fighting for Survival on Easter Island".

- ^ Tilburg, JoAnne Van (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Smithsonion Institution Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-56098-510-5.

- ^ Routledge, Katherine (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-59605-588-9.

- ^ Routledge, Katherine (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. Cosimo. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-60206-698-4.

- ^ a b Foerster, Rolf; Alvear, Alejandra (2015). El Obispo Edwards en Rapa Nui. 1910-1938 (in Spanish). Rapa Nui Press. ISBN 978-9569337079.

- ^ "Annexation by Chile". Archived from the original on 2012-02-04.

- ^ a b Diamond (2005), p. 112.

- ^ Patricia Stambuk. Iorana & Goodbye. Pehuén.

- ^ La desconocida historia de la base "gringa" albergada en Isla de Pascua

- ^ Lewis, Raymond J. (1994) "Review of Rapanui; Tradition and Survival on Easter Island.

- ^ Délano, Manuel (17 August 1987) Pinochet no asiste a la inauguración de la pista de la isla de Pascua. El Pais.

- ^ Chilean Law 20,193 Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, National Congress of Chile

- ^ "Eclipse fever focuses on remote Easter Island". NBC News. 9 July 2010.

- ^ Allen, Gerald R. (1970). "Two New Species of Frogfishes (Antennaridae) from Easter Island". Pacific Science. 24 (4): 521. hdl:10125/6262. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Police evict Rapa Nui clan from Easter Island hotel". BBC. 6 February 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Rapanui: Protests Continue Against The Hotel Hanga Roa". IPIR. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Indian Law.org". Congressman Faleomavaega to Visit Rapa Nui. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Hinto, Santi. "Giving Care to the Motherland: conflicting narratives of Rapanui". Save Rapanui. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Easter Island land dispute clashes leave dozens injured". BBC. 4 December 2010.

- ^ "Easter Island closed down by Rapa Nui Parliament".

- ^ Shore, Bradd (September 1982). "Rapanui: Tradition and Survival on Easter Island . Grant McCall". American Anthropologist. 84 (3): 717–718. doi:10.1525/aa.1982.84.3.02a00730. ISSN 0002-7294.

- ^ Bahn, Paul and John Flenley (1992). Easter Island, Earth Island. London: Thames and Hudson.

- ^ McLaughlin, Shawn (2007). The Complete Guide to Easter Island. Los Osos, CA: Easter Island Foundation.

- ^ Routledge, Katherine (2007). The mystery of Easter Island. Cosimo Classics. ISBN 978-1-60206-698-4. OCLC 540956657.

- ^ "Hazell, W. Howard". Hazell, W. Howard, (23 Aug. 1869–30 May 1929), Chairman, Hazell, Watson & Viney, LTD, printers and binders, London and Aylesbury; Chairman, Letts Diaries Co., Ltd. Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. 2007-12-01. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u211010.

- ^ Vargas, P., Cristino, C., & Izaurieta, R. (2006). 1000 años en Rapa Nui. Arqueologıa del asentamiento. Editorial Universitaria, Santiago de Chile ,

- ^ Van Tilburg, J. A. (1996). Easter Island (Rapa Nui) archaeology since 1955: Some thoughts on progress, problems, and potential. Oceanic Culture History: Essays in Honour of Roger Green., 555-577,

- ^ Stephan and Gill (2016). Skeletal Biology of the Ancient Rapanui (Easter Islanders).

- ^ Mulloy, M., & Figueroa, G. (1966). The archaeological heritage of Easter Island. UNESCO

- ^ S. Khamnueva; A. Mieth; S. Dreibrodt; W. Out; M. Madella; H. Bork (13 July 2018). "Interpretation of prehistoric reddish pit fillings on Easter Island: A micromorphological perspective". Spanish Journal of Soil Science. 8 (2): 236–57. doi:10.3232/SJSS.2018.V8.N2.07. S2CID 55155759. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Out, WA; Mieth, A; Pla-Rabés, S; Madella, M; Khamnueva-Wendt, S; Langan, C; Dreibrodt, S; Merseburger, S; Bork, H-R (2020-12-29). "Prehistoric pigment production on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), c. AD 1200–1650: New insights from Vaipú and Poike based on phytoliths, diatoms and 14C dating". The Holocene. 31 (4): 592–606. doi:10.1177/0959683620981671. S2CID 232291019.

- ^ HeritageDaily (2020-12-30). "New Findings About Prehistoric Easter Island". HeritageDaily – Archaeology News. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

Bibliography

[edit]- Diamond, Jared (2005). "Twilight at Easter". Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303655-6.

- Fischer, Steven (2005). Island at the End of the World. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1861892829.

- Pelta, Kathy (2001). Rediscovering Easter Island. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications. ISBN 978-0-8225-4890-4. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

james cook easter island.

External links

[edit] Easter Island travel guide from Wikivoyage

Easter Island travel guide from Wikivoyage- Easter Island – The Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui – Bradshaw Foundation / Dr Georgia Lee

- Chile Cultural Society – Easter Island

- Rapa Nui Digital Media Archive – Creative Commons – licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas, focused in the area around Rano Raraku and Ahu Te Pito Kura with data from an Autodesk/CyArk research partnership

- Mystery of Easter Island – PBS Nova program

- Description of island and discussion of dating controversies Archived 2017-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "Easter Island – Mysteries & Myths". Joseph Rosendo’s Travelscope. 2011. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- "From Genocide to Ecocide: the Rape of Rapa Nui " — Benny Peiser. Energy & Environment 16, no. 3/4 (2005): 513–39. Accessed March 8, 2021.