Norman Lindsay

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Norman Lindsay | |

|---|---|

Lindsay in 1921, photographed by Harold Cazneaux | |

| Born | Norman Alfred William Lindsay 22 February 1879 Creswick, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 21 November 1969 (aged 90) Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5, including Jack and Philip |

| Notes | |

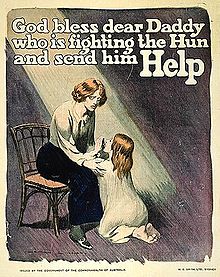

Norman Alfred William Lindsay (22 February 1879 – 21 November 1969) was an Australian artist, etcher, sculptor, writer, art critic, novelist, cartoonist and amateur boxer.[3] One of the most prolific and popular Australian artists of his generation, Lindsay attracted both acclaim and controversy for his works, many of which infused the Australian landscape with erotic pagan elements and were deemed by his critics to be "anti-Christian, anti-social and degenerate".[4]

A vocal nationalist, he became a regular artist for The Bulletin at the height of its cultural influence, and advanced staunchly anti-modernist views as a leading writer on Australian art. When friend and literary critic Bertram Stevens argued that children like to read about fairies rather than food, Lindsay wrote and illustrated The Magic Pudding (1918), now considered a classic work of Australian children's literature.

Apart from his creative output, Lindsay was known for his larrikin attitudes and personal libertine philosophy, as well as his battles with what he termed "wowserism" (strict moral conservatism). One such battle is portrayed in the 1994 film Sirens, starring Sam Neill as Lindsay and filmed on location at Lindsay's home in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. It is now known as the Norman Lindsay Gallery and Museum and is maintained by the National Trust of Australia.

Personal life

[edit]

Lindsay was born in Creswick, Victoria, the son of Anglo-Irish surgeon Robert Charles William Alexander Lindsay (1843–1915) and Jane Elizabeth Lindsay (1848–1932), daughter of Rev. Thomas Williams, Wesleyen missionary, from Creswick. The fifth of ten children, he was the brother of Percy Lindsay (1870–1952), Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961), Ruby Lindsay (1885–1919), and Daryl Lindsay (1889–1976).

Lindsay married Catherine (Kate) Agatha Parkinson, in Melbourne on 23 May 1900. Their son Jack was born in Melbourne on 20 October 1900, followed by Raymond in 1903 and Philip in 1906. They divorced in 1918. He later married Rose Soady who was also his business manager, a most recognisable model, and the printer for most of his etchings.[5]

They had two daughters: Jane Lindsay, born in 1920, and Helen Lindsay, born in 1921. Philip died in 1958 and Raymond in 1960. In the Lindsay tradition, Jack became a prolific publisher, writer, translator and activist. Philip became a writer of historical novels, and worked for the film industry.

Lindsay is buried in Springwood Cemetery in Springwood, close to Faulconbridge where he lived.

Career

[edit]

In 1895, Lindsay moved to Melbourne to work on a local magazine with his older brother Lionel. His Melbourne experiences are described in Rooms and Houses.

In 1901, he and Lionel joined the staff of the Sydney Bulletin, a weekly newspaper, magazine and review. His association there would last fifty years.

Lindsay travelled to Europe in 1909, Rose followed later. In Naples he began 100 pen-and-ink illustrations for Petronius' Satyricon.[6] Visits to the then South Kensington Museum where he made sketches of model ships in the museum's collection stimulated a lifelong interest in ship models. The Lindsays returned to Australia in 1911.

Lindsay wrote the children's classic The Magic Pudding which was published in 1918.

Many of his novels have a frankness and vitality that matches his art. In 1930 he created a scandal when his novel Redheap, supposedly based on his hometown, Creswick, was banned due to censorship laws.

In 1938, Lindsay published Age of Consent, which described the experience of a middle-aged painter on a trip to a rural area, who meets an adolescent girl who serves as his model, and then lover. The book, published in Britain, was banned in Australia until 1962.[7]

Lindsay also worked as an editorial cartoonist, notable for often illustrating the racist and right-wing political leanings that dominated The Bulletin at that time; the "Red Menace" and "Yellow Peril" were popular themes in his cartoons. These attitudes occasionally spilled over into his other work, and modern editions of The Magic Pudding often omit one couplet in which "you unmitigated Jew" is used as an insult.

Lindsay was associated with a number of poets, such as Kenneth Slessor, Francis Webb and Hugh McCrae, influencing them in part through a philosophical system outlined in his book Creative Effort. He also illustrated the cover for the seminal Henry Lawson book, While the Billy Boils. Lindsay's son, Jack Lindsay, emigrated to England, where he set up Fanfrolico Press, which issued works illustrated by Lindsay.

Lindsay influenced numerous artists, notably the illustrators Roy Krenkel and Frank Frazetta; he was also good friends with Ernest Moffitt.

Works

[edit]

Lindsay is widely regarded as one of Australia's greatest artists,[by whom?] producing a vast body of work in different media, including pen drawing, etching, watercolour, oil and sculptures in concrete and bronze. Lindsay's creative output was vast, his energy enormous. Several eyewitness accounts tell of his working practices in the 1920s. He woke early and produced a watercolour before breakfast. By mid-morning, he would be in his etching studio where he worked until late afternoon. In the afternoon, he worked on a concrete sculpture in the garden. In the evening, he'd write a new chapter for whatever novel he was working on at the time.

As a break, he worked on a model ship some days. He was highly inventive, melting down the lead casings of oil paint tubes to use for the figures on his model ships, made a large easel using a door, carved and decorated furniture, designed and built chairs, created garden planters, Roman columns and built his own additions to the Faulconbridge property.

A large body of his work is housed in his former home at Faulconbridge, New South Wales, now the Norman Lindsay Gallery and Museum, and many works reside in private and corporate collections. His art continues to climb in value today. In 2002, a record price was attained for his oil painting Spring's Innocence, which sold to the National Gallery of Victoria for A$333,900.

Reception

[edit]His frank and sumptuous nudes were highly controversial, and critics' evaluations vary considerably; in 1934 Basil Burdett called the women "fleshy strumpets"; English writer Hesketh Hubbard condemned a Lindsay exhibition in London in 1923 as "salacious"; Australian art critic Alan McCulloch at the time of Lindsay's death, called Lindsay's figures "galumphing";[9]

To gain an instant local response (and perhaps an audience overseas?) he exaggerated grossly the erotic and sensational elements. The people he drew were always in shocking taste whether nude or clothed and his humor was the 'sick' humor of the Roman forum.[citation needed]

Poet A.D. Hope in a book of Lindsay pencil drawings wrote that:

These are faithful and loving studies of the model in which the breasts and thighs are as individual and eloquent as the faces, and every part of the body thinks, feels and speaks.[10]

In 1940, Lindsay took sixteen crates of paintings, drawings and etchings to the U.S. to protect them from the war. Unfortunately, they were discovered when the train they were on caught fire and were impounded and subsequently burned as pornography by American officials. The artist's older brother Lionel remembered Lindsay's reaction: "Don't worry, I'll do more."[11][better source needed]

Screen versions of Lindsay's work

[edit]Film

[edit]The first major screen adaptation of Lindsay's literary works was the 1953 British film Our Girl Friday, based on his 1934 novel The Cautious Amorist. The 1969 Australian-British co-production Age of Consent, adapted from Lindsay's 1938 novel of the same name, was the last full-length feature film directed by Michael Powell[N 1], and starred James Mason and Helen Mirren in her first credited movie role.

In 1994, Sam Neill played a fictionalised version of Lindsay in John Duigan's Sirens, set and filmed primarily at Lindsay's Faulconbridge home. The film is also notable as the movie debut of Australian supermodel Elle Macpherson.

Television

[edit]In 1972 five novels were adapted for TV as part of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Norman Lindsay festival. These were Halfway to Anywhere (adapted by Cliff Green), Redheap (adapted by Eleanor Witcombe), A Curate in Bohemia (adapted by Michael Boddy), The Cousin from Fiji (adapted by Barbara Vernon) and Dust or Polish (adapted by Peter Kenna).[12]

Searches of the ABC's TARA Online television database,[13] and the collection database of the National Film & Sound Archive[14] conducted in March 2009, failed to return any results for these programs. Regrettably, many videotaped ABC programs, series such as Certain Women and program segments from the late 1960s and early 1970s, were subsequently erased as part of an ill-considered economy drive.

Although the closure of ABC Sydney's Gore Hill studio, uncovered considerable quantities of film and video footage long thought to have been lost, such as the complete The Aunty Jack Show, the absence of any reference on the TARA or NFSA databases and the paucity of citations elsewhere, e.g. IMDb, suggest that the master recordings of the adaptations of the Norman Lindsay novels may no longer exist. The first broadcasts of these programs predated widespread domestic ownership of videocassette recorders in Australia, so it is unlikely that any domestically recorded off-air copies exist either.

Bibliography

[edit]

Novels

[edit]- A Curate in Bohemia (1913)

- Redheap (1930) (published in the U.S. as Every Mother's Son)

- Miracles by Arrangement (1932) (published in the U.S. as Mr. Gresham and Olympus)

- Saturdee (1933)

- Pan in the Parlour (1933)

- The Cautious Amorist (1934) (first published in the U.S. in 1932); movie version: Our Girl Friday 1953

- Age of Consent (1938); movie version: Age of Consent 1969

- The Cousin from Fiji (1945)

- Halfway to Anywhere (1947)

- Dust or Polish? (1950)

- Rooms and Houses (1968)

Children's books

[edit]- The Magic Pudding 1918

- The Flyaway Highway 1936

Poetry book

[edit]- illustrations in Francis Webb A Drum for Ben Boyd Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1948

Other

[edit]- Creative Effort: An essay in affirmation 1924

- The Etchings of Norman Lindsay 1927, London, Constable & Co.

- Hyperborea: Two Fantastic Travel Essays 1928

- Madam Life's Lovers: A Human Narrative Embodying a Philosophy of the Artist in Dialogue Form 1929, London, Fanfrolico Press

- The scribblings of an idle mind 1956

- Norman Lindsay: Pencil Drawings 1969, Angus & Robertson, Sydney

- Norman Lindsay's pen drawings 1974

Autobiographical

[edit]- Bohemians of the Bulletin 1965

- My Mask (autobiography) 1970

Books about Norman Lindsay

[edit]- John Hetherington, Writers and Their Work: Norman Lindsay, 1962, Melbourne: Lansdowne Press.

- Rose Lindsay, Model Wife: My Life with Norman Lindsay, 1967, Sydney: Ure Smith.

- Jane Lindsay, A Portrait of Pa, 1975, Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- Douglas Stewart, Norman Lindsay: A Personal Memoir, 1975

See also

[edit]- Kenneth G. Ross: author of the musical play Norman Lindsay and his Push in Bohemia (1978)

- Norman Lindsay Gallery and Museum

- Margaret Coen

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972) was made after this and is a bit too long at 55 minutes to be considered a short film, but is shorter than most feature films.

References

[edit]- ^ Bernard Smith (1986). "Lindsay, Norman Alfred (1879–1969)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 10. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Ana Carden-Coyne (2005). "Lindsay, Rose (1885–1978)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Supplemental. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Norman was extremely interested in boxing and was himself an accomplished amateur. He kept a pair of gloves hanging on a nail behind his studio door and boxed whenever he could find a sparring partner. Nat, a male model and former professional boxer, gave Norman lessons in the studio.", Bloomfield, (1984), p.42.

- ^ Tully, Caroline (1992). The Pagan Lindsay. Ostara. GE Vol. XXV, 10. NO. 96, pp. 1–3.

- ^ "Norman Lindsay - Biography".

- ^ The Satyricon (Illustrated Edition), Barnes & Noble, Retrieved 28 June 2017

- ^ John Baxter (10 February 2009). Carnal Knowledge: Baxter's Concise Encyclopedia of Modern Sex. HarperCollins. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-06-087434-6. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ "Venus Crucified". The National Advocate. New South Wales. 20 September 1913. p. 4. Retrieved 1 July 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Maslen, Geoff (18 April 1986). "Exposing Lindsay to a fitful market". The Age. p. 11.

- ^ Lindsay, Norman (1969). Norman Lindsay : pencil drawings. Angus and Robertson. ISBN 0-207-95217-5. OCLC 222975289.

- ^ "Norman Lindsay Biography". ww.normanlindsay.com. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Filmography – Norman Lindsay". IMDb. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ "TARA Online". ABC Content Sales. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ "NFSA - Easy Search". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bloomfield, L., Norman Lindsay: Impulse to Draw, Bay Books, (Sydney), 1984. ISBN 0858355558

- Hetherington, J., Norman Lindsay: The Embattled Olympian, Oxford University Press, (Melbourne), 1973.

- Wingrove. K. (ed.), Norman Lindsay on Art, Life and Literature, University of Queensland Press, (St. Lucia), 1990.

External links

[edit]- Norman Lindsay Gallery

- The Norman Lindsay Website – facsimile etchings and books

- Lionel's account

- Norman Lindsay at the National Library of Australia,

- Works by Norman Lindsay at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Norman Lindsay at the Internet Archive

- Works by Norman Lindsay at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Norman Lindsay at Australian Art

- Joanna Mendelssohn 'Norman Lindsay's The Cousin from Fiji and the Lindsay Family Papers' JASAL 4 (2005)

- Silas Clifford-Smith (2008). "Lindsay, Norman". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2015.[CC-By-SA]

- Norman Lindsay at Library of Congress, with 65 library catalogue records

- Norman Lindsay

- 1879 births

- 1969 deaths

- 20th-century Australian novelists

- Australian cartoonists

- Australian children's writers

- Australian male novelists

- Australian watercolourists

- Modern artists

- People from the Blue Mountains (New South Wales)

- 20th-century Australian painters

- 20th-century male artists

- Australian bibliophiles

- Lindsay family

- People from Creswick, Victoria

- 20th-century Australian sculptors

- 20th-century Australian male writers

- Australian etchers

- Australian art critics

- Australian propagandists

- Australian male painters

- Australian people of Irish descent

- Australian people of English descent