Eccles, Greater Manchester

| Eccles | |

|---|---|

Eccles Cross | |

Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 38,756 (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SJ778986 |

| • London | 165 mi (266 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MANCHESTER |

| Postcode district | M30 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Eccles (/ˈɛkəlz/) is a market town in the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England,[1] 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Salford and 4 miles (6.4 km) west of Manchester, split by the M602 motorway and bordered by the Manchester Ship Canal to the south. The town is famous for the Eccles cake.

Eccles grew around the 13th-century Parish Church of St Mary. Evidence of pre-historic human settlement has been discovered locally, but the area was predominantly agricultural until the Industrial Revolution, when a textile industry was established in the town. The arrival of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway led to the town's expansion along the route of the track linking those two cities.

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]The derivation of the name is uncertain, but two suggestions have been proposed. The received one is that the Eccles place-name is derived from the Romano-British Ecles or Eglys (eglwys in Welsh means 'church'), which in turn is derived from the Ancient Greek ecclesia via the Latin.[2] Following the arrival in AD 613 of the invading Anglo-Saxons in Lancashire, many existing British place-names, especially rivers and hills (the River Irwell for example), survived intact. The root Ecles, found in several village names, could be an example of this. So, the suggestion is that the word denoted the site of a building, or a ruin featuring the landscape, which was recognised by the Anglo-Saxons as a church. Eccles would then have been a village founded around one such, and so Ecles may be the likely source of the modern name.[3][4] In Kenyon's Origins of Lancashire (1991), however, the author casts doubt on the further suggestion that native British Church administration survived into Anglo-Saxon times, as there is not an exact correlation between Eccles place-names and pre-Domesday hundreds in south Lancashire.[2]

An alternative etymology is derived from that known to belong to Eccles in Kent, recorded as "Aiglessa" in the Domesday Book of 1086 and so conclusively deriving from the Old English (pre 7th century) æc-læas meaning 'oak pasture'.[5]

Early history

[edit]Pre-historic finds in the parish of Eccles include dugout boats found at Barton upon Irwell, an arrowhead, a spear and axes at Winton, which taken together appear to suggest the existence of a hunting and travelling society. Human habitation in the area may extend as far back as 6000 BC, with two separate periods of settlement on Chat Moss, the first around 500 BC and the second during the Romano-British period.[6]

The village may have been founded by refugees from Manchester (Mamucium) during the Diocletianic Persecution in the early 4th century,[3] although excavations in 2001–2005 revealed that the civilian settlement at Manchester had probably been abandoned by the mid-3rd century.[7] Throughout the Dark Ages the parish appears to have been remote enough to be untouched by any local conflicts, while absorbing successive waves of immigrants from nearby towns.[8]

The Manor of Barton upon Irwell once covered a large area; in 1276 it included townships such as Asphull, Halghton, Halliwelle, Farnword, Eccles, Workedele, Withington (latterly Winton), Irwelham, Hulm, Quicklewicke, Suynhul and Swinton. Before this date it would appear to have been even larger, but by 1320 the manor boundaries were described as "Tordhale Siche descending to Caldebroc, then to the pit near Preste Platteforde and then to another pit, then to the ditch of Roger the Clerk, then to the hedge of Richard the Rimeur, then following the hedge to Caldebroc."[9] The manor was originally controlled by the Barton family until about 1292 when by marriage it came into the ownership of the Booth family, who retained it for almost 300 years. In 1586 the Trafford family assumed control of the manor, and established themselves in 1632 at Whittleswick, which was renamed Trafford Park.[10]

The parish of Eccles contained the townships of Barton upon Irwell, Clifton, Pendlebury, Pendleton and Worsley.[11] Toward the end of the Middle Ages the parish had an estimated population of about 4,000 Communicants. Agriculture remained an important local industry, with little change from the Medieval system due to a lack of adequate drainage and fertiliser.[12] No evidence exists to demonstrate the layout of the area, but it would likely have been the same as the surrounding areas of Salford, Urmston and Warrington where oats and barley would have been grown.[13] Local cottage industries included blacksmiths, butchers, thatching, basket weaving, skinning and tanning. Weaving was popular, using linen and wool;merchants traded in corn; badgers bought and sold local produce.[14]

Although the local gentry supported the Royalists, the English Civil War had little effect on the area. Troops would occasionally pass through the parish[15] and there was a skirmish at Woolden,[16] but the only other mention of local involvement was the burial of two (probably) local soldiers in 1643.[15] The Jacobite army passed through in 1745, in its advance and subsequent retreat.[16]

Textiles and the Industrial Revolution

[edit]

In 1795 John Aikin described the area:

The agriculture of the parish is chiefly confined to grazing, and would be more materially benefited by draining; but the tax upon brick, a most essential article in this process, has been a very great hindrance to it. The use of lime—imported from Wales, and brought by the inland navigations to the neighbourhood of our collieries—has become very general in the improvement of the meadow and pasture lands.[16]

During the 18th century the predominance of textiles in the region is partly demonstrated in the parish registers of 1807, which show that 46 children were baptised with 34 fathers employed as weavers.[17] In Memoirs of seventy years of an eventful life (1852) Charles Hulbert wrote:

The principal employment of the working population of Eccles and vicinity at that time, was the manufacture of Cotton Goods on the home or domestic plan. These were not then, according to my present recollection, more than two Spinning Manufactories in Manchester, Arkwright's with its loft chimney, and Douglas's extensive Works, on the River Irwell, near the Broken bank ... At the period of my first residence in Eccles Parish, I believe the above Mills chiefly supplied the Weavers of Eccles and other parishes with twist for warps, which were purchased by the Master Manufacturers.[18]

During the early 19th century the growth of industry meant the majority of the area's inhabitants were employed in textiles or trade, while a minority worked in agriculture. The factory system was also introduced; in 1835, 1,124 people were employed in cotton mills, and two mills used power looms. Local hand-produced specialities included striped cotton ticks, checks, Nankeens and Camrays. Two cotton mills are visible on the 1845 Ordnance Survey map of the area. The area also became renowned for its production of silk, with two mills at Eccles and one at Patricroft. Many factory workers were children under 12 years of age.[19]

In 1830 James Nasmyth (son of Alexander Nasmyth) visited the newly opened Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and on his return to Manchester noted the suitability of a site alongside the canal at Patricroft for an engineering works.[20][21] He and his brother leased the land from Thomas de Trafford, and established the Bridgewater Foundry in 1836. The foundry was completed the following year with a design based upon assembly line production. In 1839 Nasmyth invented the steam hammer, which enabled the manufacture of forgings at a scale and speed not seen before. In the same year the foundry started to manufacture railway locomotives, with 109 built by 1853. Nasmyth died a wealthy man in 1890.[22]

The Eccles Spinning and Manufacturing Company came into being following a meeting called by the Mayor of Eccles, in which concern was expressed at the decline in local industry. Two earlier Eccles mills had been destroyed by fire, resulting in significant local unemployment. Designed by Potts, Son and Hennings of Manchester, Bolton and Oldham, it was opened in 1906. The imposing mill contained a multi-storey spinning mill, engine house and extensive weaving sheds.[24]

Early housing in the village consisted of groups of thatched cottages clustered around and near the parish church. The influx of workers from areas around the village accompanied an increased demand for extra housing. Even after the establishment of the local board of health new properties were often built in the gardens of existing dwellings, leading to severe overcrowding. In 1852 the streets were paved with boulders, sewerage was non-existent, and water supply was a local well. During the latter half of the 19th century new housing was erected alongside the railway, and large areas of open land were soon occupied with new housing estates built for the area's more wealthy residents.[25]

The construction of the Manchester Ship Canal provided many local residents with jobs; 1,888 people were employed on the section of the new canal at Barton. A stone aqueduct over the River Iwell dating from 1761 and designed by James Brindley was demolished and replaced by a new moveable aqueduct: the Barton Swing Aqueduct.[26][27]

Post-industrial history

[edit]Eccles was not immune to the general decline of the textile industry in the 20th century. The Bridgewater Foundry ceased operations in 1940, taken over by the Ministry of Supply and converted into a Royal Ordnance Factory.[28] The factory closed in the late 1980s, and the land is now occupied by a housing estate.

Eccles is included in the City of Salford's Unitary Development Plan 2004–2016 as part of the western gateway, a major focus for economic development during the plan period. Areas to be developed include the Barton Strategic Regional Site, Dock 9 at Salford Quays, Weaste Quarry near Eccles, and remaining land at Northbank, and the plan provides for improvements which include the A57 – Trafford Park link at Barton and provisional support for a further expansion of the Metrolink system through the area and a link between the A57 and M62 at Barton.[29] Under this plan the town's retail environment would also be maintained and enhanced.[30]

Governance

[edit]

In 1854 the Barton, Eccles, Winton and Monton Local Board of Health was established for the northern part of the township of Barton. Eccles was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1892, part of which was in Barton poor law union, an inter-parish unit established to provide social security, and in 1933 this was expanded to include most of Barton Moss civil parish, and part of Worsley Urban District. A small part of the borough was transferred in 1961 to the County Borough of Salford. In 1974 the borough was abolished and its area transferred to Greater Manchester to form part of the City of Salford.[31]

The Eccles area incorporates the wards of Barton, Winton, and Eccles.[32]

Following its review of parliamentary representation in Greater Manchester, the Boundary Commission for England recommended that Eccles be split between two new constituencies; Salford and Eccles, from the existing Salford constituency and the central/eastern part of Eccles, and Worsley and Eccles South, from the existing Worsley constituency and the southern/western part of Eccles.[33]

Geography

[edit]Eccles is 3.7 miles (6 km) west of Manchester, on the north bank of the Manchester Ship Canal.[34] The area is along a gentle slope from 160 feet (49 m) above sea level to the north, to 60 feet (18 m) above sea at the south, near the Irwell.[35] The underlying geology is made up of New Red Sandstone and pebble beds. The coal measures of the Lancashire coalfield extend south to Monton and Winton. On the surface deposits of clay and loose sands are prevalent throughout the area, along with vegetable moulds formed by rotted vegetation from the previous ice age. These areas have, when drained, provided fertile soil for local agriculture, benefited by the 19th century practice of dumping nightsoil from nearby Manchester.[36]

Parts of the area are within an indicated floodplain.[37] Eccles' climate is generally temperate, like that of the rest of Greater Manchester. The mean highest and lowest temperatures (13.2 °C (55.8 °F) and 6.4 °C (43.5 °F)) are slightly above the national average, while the annual rainfall (806.6 millimetres (31.76 in)) and average hours of sunshine (1394.5 hours) are respectively above and below the national averages.[38][39]

Demography

[edit]Overall

[edit]At the 2001 Census, Eccles was part of the Greater Manchester Urban Area and had a population of 36,610, of which 17,924 (48.96%) were male and 18,686 (51.04%) female. It occupied 812 hectares, compared with 783 at the 1991 census, a population density of 45.09 people per hectare compared with an average of 40.20 across the Greater Manchester Urban Area.[40] The median age of the population is 37, compared with 36 within the Greater Manchester Urban Area and 37 across England and Wales.[41]

The majority of the population of Eccles was born in England (91.94%); 2.61% were born elsewhere within the United Kingdom, 0.70% within the rest of the European Union, and 2.99% elsewhere in the world.[42]

Data on religious beliefs across the town in the 2001 census show that 77.07% declared themselves to be Christian, 12.05% said they held no religion, and 2.26% reported themselves as Muslim.[43]

Eccles is within the Manchester larger urban zone,[44] and the Manchester travel to work area.[45]

| Eccles compared | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Census 2001 | Eccles | Greater Manchester Urban Area |

England | |

| Total population | 36,610 | 2,244,931 | 49,138,831 | |

| Born outside UK | 5.5% | 7.9% | 9.2% | |

| White | 95.8% | 90.3% | 91.0% | |

| Asian | 2.1% | 6.2% | 4.6% | |

| Black | 0.4% | 1.3% | 2.3% | |

| Over 75 years old | 8.6% | 7.1% | 7.5% | |

| Christian | 77.1% | 72.9% | 72% | |

| Muslim | 2.3% | 5.5% | 3.1% | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics[40][46][43] | ||||

| Population change in Eccles from 1901 to 2011 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Population | 34,369 | 41,944 | 44,242 | 44,416 | 41,512 | 43,926 | 43,173 | 38,511 | 37,792 | 36,000 | 36,610 | 38,756 |

|

Municipal Borough 1901–1971[47] • Urban Subdivision 1981–2011[48][40][49][50] | ||||||||||||

By ward

[edit]The Eccles area consists of the wards of Barton, Winton, and Eccles.[32]

According to the Office for National Statistics, at the time of the United Kingdom Census 2001, the ward of Eccles had a population of 11,413, of which 5,546 were male, and 5,867 female.[51] The ward of Winton had a population of 12,752,[52] and the ward of Barton had a population of 10,434,[53] giving the larger administrative area of Eccles a total population of 34,599.

Eccles is the ninth-most densely populated ward in Salford, and has the highest number and proportion of people aged 75 and over of all wards in Salford. Levels of crime are below the average for the city. The adult population tends to be more qualified than the city average, and primary and secondary education results are also slightly higher than average for Salford. Unemployment is below average, with people tending to work longer hours. More residents live in purpose-built and converted flats than do in the city as a whole, with a minority occupying detached houses or bungalows. Between 1994 and 2004, 367 homes were added to the ward, above the average for Salford.[54]

Neighbouring Winton is the sixth-most densely populated ward in the region and in 2001 had proportionally more children than the city as a whole. Crime is generally below average, with falling rates of burglary in 2005. Education standards for both adults and children are below city average with minor improvements to GCSE results between 2005 and 2006. Unemployment is higher than average for Salford, with areas of severe income deprivation both to the north and south of the ward. Residents are on average more likely to live in semi-detached housing, with 208 homes added between 1994 and 2004.[56]

To the south, the ward of Barton is the third most densely populated in Salford with little population change between 1991 and 2001. It has proportionally more over-85-year-olds than the city as a whole, with low adult and primary school education standards, but significant improvements in GCSE results of late. Some parts of Barton are amongst the worst 20% of areas in the country for child poverty, with below-city-average childcare provision. Unemployment is higher than average for Salford. Almost half the homes in the ward are terraced housing, with an extra 300 properties built between 1994 and 2004.[57]

Economy

[edit]To the east of the town centre, the West One retail park was opened in November 2001 at a cost of £53m. It is in competition with the nearby Trafford Centre and Lowry Outlet Mall, and as a result has suffered a loss of trade. Most of its units were abandoned but following the decision by Tesco to scrap plans for a £30m Tesco Extra store in 2013[58] a number of new openings have improved the retail offering; The Range,[59] Home Bargains,[60] Smyths Toys Superstores.,[61] PureGym[62] and Jollyes Petfood Superstore.[62] A Morrisons supermarket is near the town centre.[63] One of the UK's largest online lighting retailers Value lights, is also located in an 80,000 square foot distribution centre in the centre of Eccles.[64]

Until shortly after its closure was announced on 9 May 2006, the Great Universal Stores group used the former Eccles Spinning and Manufacturing Company building in Winton. Operations have since been transferred to a site in Shaw and Crompton.[24][65] The town still has a manufacturing industry. Valtris Speciality Chemicals (Ackros Chemicals prior to April 2016[66]), a leading chemical additive supplier and its predecessors have occupied a site on Lankro Way since 1937, the site in Eccles employs more than 100 people working in manufacturing, research, administrative and business management roles.[67][68] Americhem Europe manufactures colouring for plastics and nylon fibres, employing 75 staff with a turnover of £10m.[69] The Eccles-based insurance broker and financial services specialist CBG Group, which worldwide employs 180 people, has its head office near the town centre.[70] The employment agency Morson Group has its headquarters in Eccles and supplies thousands of employees to various hi-tech employers.[71]

Eccles cakes, first produced and sold in the town in 1796, are now exported across the world.[72]

Landmarks

[edit]

The Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin is the only Grade I listed building in Eccles.[73] There are two Grade II* listed buildings in the Eccles area. The Church of St Andrew was completed by the architect Herbert Edward Tijou in 1879.[74][75] Monton Unitarian Church was completed in 1875 by Thomas Worthington.[76]

The town's war memorial was erected in 1925. Local sculptor John Cassidy was commissioned to design the structure. Built from Portland stone and topped with a bronze figure, it was unveiled by Lord Derby in August 1925. It is now a Grade II listed building.[77]

Eccles Library was built on a slum clearance site in the town centre. The building was funded by Andrew Carnegie and designed by Edward Potts (who also designed the canalside mill picture above), and opened on 19 October 1907. Designed in the Renaissance style, it is now a Grade II listed building. Potts had hoped that the building would become "the Eccles University".[77][78] The former Lyceum Theatre on Church Street is a Grade II listed building.

Salford City Council is currently bidding for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway to be included in UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites. Eccles railway station has recently undergone restoration work by the 'Friends of Eccles Railway Station', including clean-ups, renovation of the station garden, and a mural.[79]

Both Monton Green and Ellesmere Park are designated conservation areas,[80] and a Site of Biological Importance is located near Rutland Road and Chatsworth Road.[81]

Transport

[edit]

The Salford to Warrington turnpike trust was formed in 1752 and assumed control of the road from Pendleton to Irlam. Opinions as to the quality of the road were mainly negative; writing in 1795, John Aikin said "Much Labour and a very great expense of money have been expended on the roads of this parish, but they still remain in a very indifferent state, and from one plain and obvious cause, the immoderate weights drawn in carts and waggons."[82] On the poor quality roads, the Liverpool to Manchester stagecoach took almost an entire day to make the journey. Matters appear to have improved by the 19th century, along with the opening of several more trust roads throughout the parish. In the early part of the 19th century some existing routes were widened and straightened, including the modern-day Regent Road in Salford. All the roads except one were surfaced with boulders.[82] In 1832 a daily omnibus service from Manchester reached Eccles and Pendleton. In 1877, following the laying of tracks in the road, horse-drawn trams were used; these eventually gave way in 1902 to electric trams under the control of the Salford Corporation. Motorised buses were introduced in 1938.[82]

The opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on 15 September 1830 was a pivotal moment in transport history. The world's first railway constructed to carry passengers as well as freight, it signalled the beginning of the end for both the turnpike trusts and the canal system. Stagecoach services ceased as passengers started to use the faster railway.[20] The opening day was historic for more than one reason though; Eccles became a part of an early railway accident. During a stop at Parkside railway station near Newton-le-Willows, Member of Parliament for Liverpool, William Huskisson was seriously injured by an approaching locomotive. He was taken to the vicarage in Eccles for treatment, but died of his injuries.[83] There have been two further serious railway incidents in Eccles, the first in 1941,[84] and the second in 1984.[85] The line was widened in 1882, and improvements were made to the station infrastructure, however on 11 January 1971 a fire destroyed the wooden station building, which has never been rebuilt.[86]

The Tyldesley Loopline was opened by the London and North Western Railway on 1 September 1864 with stations at Monton Green (opened 1887), Worsley, Tyldesley and Leigh. The railway provided a link between Eccles (located on the existing Liverpool and Manchester line) and Wigan. In 1870 an additional branch line from this, the Roe Green Loopline, was opened to Bolton to support the surrounding collieries, the largest of which was at Mosley Common.[87] The London and North Western Railway also built a line from Patricroft railway station to Molyneux Junction, via Clifton Hall Tunnel (built in 1849).[88] The line connected with the East Lancashire Railway to Radcliffe and Bury. Clifton Hall Tunnel collapsed on 28 April 1953.[88] The Tyldesley Loopline was closed on 5 May 1969 under the Beeching axe, and the closure of the Roe Green branch line followed in October 1969.[87]

In 1851 the Earl of Ellesmere hosted a visit to Manchester by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. They stayed at Worsley Hall, with a view of the canal, and were given a trip between Patricroft railway station and Worsley Hall, on state barges. Large crowds had gathered to cheer the royal party, which apparently frightened the horses drawing the barge so much that they fell into the canal.[89]

The M602 motorway was opened throughout on 3 November 1971. The Borough Council had previously formed the Eccles Borough Council's General Purposes Committee, which from December 1962 began to purchase land for the route of the new road, while overseeing a powerful public relations scheme. A demolition programme commenced in January 1967, with some residents re-housed in newly built housing stock. The council also had to arrange for the purchase of land at the interchange with the present-day M60, and to re-route part of the Thirlmere Aqueduct. Construction began on 8 December 1969, along a route limited by the existence of housing estates, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the M62 junction at Worsley, and the Bridgewater Canal. Consideration was given to the route of the disused Eccles-Tyldesley-Wigan railway line; the height of the motorway was lowered to accommodate a new railway bridge in case the line was ever re-instated. The nearby bridge for the Clifton Junction branch railway was demolished with explosives.[90]

In addition to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the town is now served by the Eccles Line of the Metrolink light rail system which, along with regular bus services, terminates at Eccles Interchange.[91] Work on the Metrolink branch to Eccles began in July 1997 and was completed by July 2000, with the official opening ceremony in January 2001;[92] trams leave every twelve minutes.[93]

Education

[edit]One of the early schools in Eccles was the 18th century day school in the parish of St. Mary's, south of the Irwell on the de Trafford estate. A Catholic Sunday school was opened in Eccles during the 19th century, in a building in Back Timothy Street (now the location of Eccles Library). Another day school was also opened in cottages on Barton Lane. The first substantial school in the area however was opened in 1851 along Church Street. A boys' school was opened in 1888.[94]

St Patrick's RC High School is currently the best-performing secondary school in Salford, with one of the highest scores in England.[95] The Eccles area contains a number of primary and secondary schools, including (but not limited to) St. Mary's R.C. Primary School, Branwood Preparatory School,[96] New Park High School and Monton Green Primary School.

Eccles College is a further-education college. It opened in 1973 and provides a wide range of A-level and vocational course for school-leavers.[97]

Religion

[edit]As the population of Eccles increased during the Industrial Revolution the medieval parish of Eccles was gradually divided into smaller parishes, and surrounding townships gained their own churches. The Grade II* listed St Andrew's church in St Andrew's Parish was built in the 1870s and opened in 1879 (the tower was added in 1889). Over the next 40 years various decorative improvements were made to the building, including stone carvings, stained glass, and wall paintings (covered in 1965). Four months after the church was consecrated a church school was opened, the forerunner of the present St Andrew's Primary School. A second school in Monton (then part of the parish) opened in 1881. In 1912 Monton became a separate parish with its own church, St Paul's.[98]

Roman Catholics living in Eccles originally attended worship at a chapel on the de Trafford estate, south of the Irwell, however the chapel was demolished and replaced by All Saints' Church. The first Rector of the Roman Catholic Parish of Eccles was, from 1879, a Father Sharrocks. The first public Roman Catholic procession in Eccles since the Reformation took place on 18 August 1889.[94]

The area has a variety of other churches, including the Church of St James at nearby Hope,[99] and a Baptist church.[100] Other denominations catered for include Methodist New Connexion, Zion Methodist New Connexion, Wesleyan, and The Salvation Army (opened in 1881).[101]

Sport

[edit]The amateur rugby union club Eccles Rugby Football Club were winners of a cup competition organised by Swinton Lions on 4 January 1881 and were first recorded as members of the Lancashire County Rugby Football Union in 1886.[102] Eccles RFC joined the RFU in 1887 but following the Northern Union schism in 1895, the club was re-established in 1897 and has maintained its existence since. Before the first world war Eccles played its rugby at Peel Green Road close to the Barton Swing Aqueduct, between the wars it played on the opposite bank of the Manchester Ship Canal at Redclyffe Road close to Barton Power Station, before moving to its current ground at Gorton Street in the summer of 1948.

The amateur rugby league club Salford City Roosters, formerly known as the Eccles Roosters, are also based in Eccles and were formed in 1977.

To the west of Eccles lies the 12,000 capacity City of Salford Stadium,[103] home to both professional Rugby League team Salford Red Devils and professional Rugby Union team Sale Sharks along with new transport infrastructure and the Trafford Centre.[104] Immediately west of the new stadium site is Boysnope Park Golf Club, an 18-hole par-72 parkland course with floodlit driving range.[105]

Eccles is home to the City of Salford Volleyball Club one of English volleyball's premier women's teams, the club competes in Volleyball England's Women's SUPER8's competition as well as having a number of development teams

Public services

[edit]

Eccles became the first municipal corporation in England to operate a motorised fire engine in 1901. It was supplied to Eccles Corporation by a local firm, the Protector Lamp and Lighting Co., also known for manufacturing Miners' Safety Lamps. Barton Aerodrome, the first municipal aerodrome in the UK to be licensed by the Air Ministry, was opened on 29 January 1930 on a site at Barton-on-the-Moss.[106]

The first Power Station in Eccles was built along Cawdor Street, and opened on 14 December 1896 by Alderman W. D. Kendall. The second and much larger Barton Power Station was built in 1920 alongside the Manchester Ship Canal and Bridgewater Canal. It was opened on 11 October 1923 by the Earl of Derby, and supplied electricity to Manchester and the South East Lancashire Electricity District. It ceased generation in March 1974, operating from thereon only as a switching station, and was demolished in June 1979.[107][108]

Salford Royal hospital opened in 1882 as the Salford Union Infirmary,[109] a hospital for sick paupers, in association with the union workhouse. It was later renamed as Hope Hospital, taking the name of the nearby medieval Hope Hall, demolished in 1956.[110] The hospital was given its current name in 2007.[111]

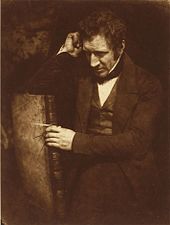

Notable people

[edit]Edward Potts was a renowned architect born on 2 March 1839 in Bury. He moved to Oldham and designed many of the town's mills and was ranked with P. S. Stott as the greatest mill architect of Victorian Lancashire. He moved to Eccles in 1891 and was responsible for the design of the town's library. He was a Liberal member of the borough council from 1902 to 1905, the first chairman of the town's library committee (1904), and a Justice of the Peace in 1906. He inaugurated popular Saturday-night concerts during the winter months and, keen to reduce the incidence of infant mortality, gave a sovereign to the mother of every child who reached the age of one. He died on 15 April 1909 and was buried at Chadderton Cemetery.[78]

The hymn-writer William Cooke was born in Eccles in 1821.[112][113]

The humanitarian aid worker Alan Henning was from Eccles before he was murdered by Jihadi John.

Culture

[edit]Eccles is perhaps best known for the Eccles cake. Dating from the 18th century, they were first sold from a shop owned by James Birch in 1793. Traditionally made in the town from a recipe of flaky pastry, butter, nutmeg, candied peel, sugar and currants, they are sold across the country and exported across the world. They are sometimes referred to as "dead fly pies".[114]

Eccles Wakes (a holiday to celebrate the dedication of the Parish Church) were celebrated annually until 1877, when the tradition was abolished by the Home Secretary. The Wakes were held over three days, beginning on the first Sunday after 25 August.[115]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names – D to F. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ^ a b Kenyon 1991, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Johnston 1962, pp. 1–4

- ^ Gelling, Nicolaisen & Richards 1970, p. 88.

- ^ "Last Name Eccles". Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Gregory 2007, p. 190.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 14.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 30.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Harland 1857, p. 589.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 37.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Johnston 1967, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Farrer & Brownbill 1911, pp. 352–362.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 84.

- ^ Hulbert 1852, p. 86.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 84–88.

- ^ a b Jackson 1962, pp. 526–527.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 89.

- ^ Tucker 1977, pp. 177–181.

- ^ Cranna, Ailsa (20 November 2008). "Trouble at mill for rare building". Salford Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Addition of the former GUS warehouse, Worsley Road, Eccles, to the council's list of buildings of local architectural or historic interest" (DOC). salford.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 102–105

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 141.

- ^ Nevell 1997, p. 135.

- ^ Cantrell 2005, p. 107.

- ^ "City of Salford Unitary Development Plan 2004–2016 chapter 189". Salford City Council. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "City of Salford Unitary Development Plan 2004–2016 chapter 190". Salford City Council. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names – D to F. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Eccles". salford.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Final Recommendations for Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries in Greater Manchester". Boundary Commission for England (North West). Government News Network. 19 July 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 1.

- ^ Johnston 1967, p. 5.

- ^ Johnston 1967, pp. 4–5.

- ^ "City of Salford Unitary Development Plan 2004–2016 chapter 208". Salford City Council. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "Manchester Airport 1971–2000 weather averages". Met Office. 2001. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ^ Met Office (2007). "Annual England weather averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ a b c "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 22 July 2004. KS02 Age structure

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 22 July 2004. KS01 Usual resident population

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 22 July 2004. KS05 Country of birth

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 22 July 2004. KS07 Religion

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Towards a Common Standard" (PDF). Greater London Authority. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "Travel to Work Areas". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 22 July 2004. KS06 Ethnic group

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Eccles MB: Total Population". Vision of Britain. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Eccles Built-up area sub division (E35000181)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas GB Table 1, Office for National Statistics, 1981

- ^ "Greater Manchester Urban Area 1991 Census". National Statistics. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ "Eccles (ward) – 2001 Census Area Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Winton (ward) – 2001 Census Area Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Barton (ward) – 2001 Census Area Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "City of Salford: Eccles ward profile". Salford City Council. 2004. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "1890 – LANCASHIRE AND FURNESS 1:2,500". old-maps.co.uk. 1890. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "City of Salford: Winton ward profile". Salford City Council. 2004. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "City of Salford: Barton ward profile". Salford City Council. 2004. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "Place North West - West One Retail Park sold for £17.7m". placenorthwest.co.uk. 7 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "The Range to open Eccles store at West One Retail Park this September - Manchester Evening News". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Eccles West One change will pave way to major Home Bargains move". salfordonline.com. 9 October 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Exclusive: Smyths Toys Superstores to open 14,000sq ft store at West One Retail Park Eccles". salfordonline.com. 15 December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b "PureGym and Jollyes Pets finally confirm West One Eccles move". Salford Online. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to Morrisons Supermarkets, Eccles". morrisons.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "thebusinessdesk.co.uk". Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Littlewoods axe 1,200 in shake-up". BBC News. 9 May 2006. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ "Valtris Specialty Chemicals, an H.I.G. Portfolio Company, Acquires Akcros Chemicals | Akcros Chemicals". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Akcros Chemicals UK Headquarters Facility with Long Term Income and Future Redevelopment Potential : For Sale" (PDF). Wsbproperty.co.uk. January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Rooth, Ben (25 March 2008). "Eccles plastics expansion". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "CBG Group raises £1.65m". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. 7 November 2008. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Strong year for Morson Group as profits surge". Archived from the original on 11 April 2016.

- ^ Ruggeri, Amanda. "The cake that comes with a warning". Bbc.com. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Historic England, "St Mary's Church (1067498)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 December 2007

- ^ Historic England, "Church of St Andrew, Eccles (1309482)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 February 2008

- ^ Salford City Council. "Index to the List of Buildings, Structures and Features of Architectural, Archaeological or Historic Interest in Salford". salford.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Historic England, "Monton Unitarian Church (1067501)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 24 February 2008

- ^ a b Wyke 2005, p. 172.

- ^ a b Farnie, D. A.; Harrison, B. (2004). "Potts, Edward (1839–1909), architect". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60877. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ "City of Salford Unitary Development Plan 2004–2016 chapter 199". Salford City Council. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "City of Salford Unitary Development Plan 2004–2016 chapter 200". Salford City Council. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ a b c Johnston 1967, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Brockbank 1965, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Wilson, Major G R S (9 April 1942). "Accident Report" (PDF). Ministry of War Transport. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Accident Enquiry Report" (PDF). HMSO. 10 June 1985. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ Rowbottom 2001, p. 6.

- ^ a b "Station Name: MONTON GREEN". Disused Stations. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ a b Collacott 1985, p. 8.

- ^ Corbett 1974, p. 43.

- ^ Johnson, W. M. (1 December 2002). "History of the M602". lancashire.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Eccles Bus Station" (PDF). GMPTE. 25 January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ Schneider 2004, p. 203.

- ^ "Tram Times". Metrolink. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b Rowbottom 2001, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Qureshi, Yakub (15 January 2009). "School goes to top of class". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Branwood Preparatory School". branwoodschool.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ "Welcome to Eccles College". Ecclescollege.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ "A brief history of St Andrew's". standrewseccles.org. 2000. Archived from the original on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Salford Deanery". manchester.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ "ChurchFinder: Church Details Eccles". baptist.org.uk. Retrieved 15 March 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Church Register List". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Eccles to Fylde. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ "Club History". ecclesrfc.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Work begins on new Salford site". BBC Sport. 14 February 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ Chapelard, James (17 February 2009). "Trafford Council okays Peel's Western Gateway scheme". crainsmanchesterbusiness.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Boysnope Park Golf Club". boysnopegolfclub.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "City Airport Manchester – North West Aviation | General Information". cityairportmanchester.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ Rowbottom 2001, p. 34.

- ^ "Power Stations in Greater Manchester" (PDF). msim.org.uk. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Cooper 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Cooper 2005, p. 84.

- ^ Crook, Amanda (12 September 2007). "Royal approval in hospital revamp". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ "Cooke, William (CK836W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Samuel Willoughby Duffield, English Hymns: Their Authors and History (1886), p. 358

- ^ "The history behind (And recipe for) Eccles Cakes - Salford City Council". Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Eccles wakes up to fun and frolics". Salford Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. 22 August 2002. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

Bibliography

- Brockbank, William (1965), The Honorary Medical Staff of the Manchester Royal Infirmary 1830–1948, Manchester University Press ND

- Cantrell, John (2005), Nasmyth, Wilson & Co.: Patricroft Locomotive Builders, Stroud: Tempus Publishing Limited, ISBN 0-7524-3465-9

- Collacott, Ralph Albert (1985), Structural Integrity Monitoring, Springer, ISBN 0-412-21920-4

- Cooper, Glynis (2005), Salford: An Illustrated History, Breedon Books Publishing Co Ltd, ISBN 1-85983-455-8

- Corbett, John (1974), Pleasant Reminiscences of the Nineteenth Century and Suggestions for Improvements in the Twentieth., E. J. Morton, ISBN 0-85972-006-3

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (1911), "The Parish of Eccles", A History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 4, British History Online, retrieved 12 February 2009

- Gelling, Margaret; Nicolaisen, W. F. H.; Richards, Melville (1970), The Names of Towns and Cities in Britain, B. T. Batsford, ISBN 9780713401134

- Gregory, Richard, ed. (2007), Roman Manchester: The University of Manchester's Excavations within the Vicus 2001–5, Oxford: Oxbow Books, ISBN 978-1-84217-271-1

- Harland, John (1857), The House and Farm Accounts of the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe Hall, in the County of Lancaster, at Smithils and Gawthorpe: From September 1582 to October 1621, Chetham society

- Hulbert, Charles (1852), Memoirs of seventy years of an eventful life, printed by the author

- Jackson, W. Turrentine (1962), The Development of Transport in Modern England, Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-1326-6

- Johnston, F. R. (1962), How Eccles got its name, Eccles ; Manchester: Eccles and District History Society

- Johnston, F. R. (1967), Eccles, the growth of a Lancashire town, Eccles ; Manchester: Eccles and District History Society

- Nevell, Mike (1997), The Archaeology of Trafford, Trafford Metropolitan Borough with University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 1-870695-25-9

- Kenyon, Denise (1991), The Origins of Lancashire, Manchester University Press ND, ISBN 0-7190-3546-5

- Rowbottom, Doreen (2001), Treasures of Eccles: Past and Present, Local Studies Group of LLL/U3A – Salford

- Schneider, Joachim (2004), Public private Partnerships for Urban Rail Transit, DUV, ISBN 3-8244-8050-6

- Tucker, K. A. (1977), Business History: Selected Readings, Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-3030-6

- Wyke, Terry (2005), Public Sculpture of Greater Manchester, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 0-85323-567-8

External links

[edit]