Dominant (music)

In music, the dominant is the fifth scale degree (![]() ) of the diatonic scale. It is called the dominant because it is second in importance to the first scale degree, the tonic.[1][2] In the movable do solfège system, the dominant note is sung as "So(l)".

) of the diatonic scale. It is called the dominant because it is second in importance to the first scale degree, the tonic.[1][2] In the movable do solfège system, the dominant note is sung as "So(l)".

The triad built on the dominant note is called the dominant chord. This chord is said to have dominant function, which means that it creates an instability that requires the tonic for resolution. Dominant triads, seventh chords, and ninth chords typically have dominant function. Leading-tone triads and leading-tone seventh chords may also have dominant function.

In very much conventionally tonal music, harmonic analysis will reveal a broad prevalence of the primary (often triadic) harmonies: tonic, dominant, and subdominant (i.e., I and its chief auxiliaries a 5th removed), and especially the first two of these.

— Wallace Berry (1976)[4]

The scheme I-x-V-I symbolizes, though naturally in a very summarizing way, the harmonic course of any composition of the Classical period. This x, usually appearing as a progression of chords, as a whole series, constitutes, as it were, the actual "music" within the scheme, which through the annexed formula V-I, is made into a unit, a group, or even a whole piece.

— Rudolph Reti, (1962)[5]

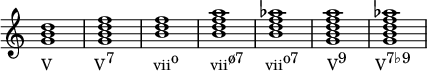

Dominant chords

[edit]

In music theory, the dominant triad is a major chord, symbolized by the Roman numeral "V" in the major scale. In the natural minor scale, the triad is a minor chord, denoted by "v". However, in a minor key, the seventh scale degree is often raised by a half step (♭![]() to ♮

to ♮![]() ), creating a major chord.

), creating a major chord.

These chords may also appear as seventh chords: typically as a dominant seventh chord, but occasionally in minor as a minor seventh chord v7 with passing function:[6]

As defined by the 19th century musicologist Joseph Fétis, the dominante was a seventh chord over the first note of a descending perfect fifth in the basse fondamentale or root progression, the common practice period dominant seventh he named the dominante tonique.[7]

Dominant chords are important to cadential progressions. In the strongest cadence, the authentic cadence (example shown below), the dominant chord is followed by the tonic chord. A cadence that ends with a dominant chord is called a half cadence or an "imperfect cadence".

Dominant key

[edit]

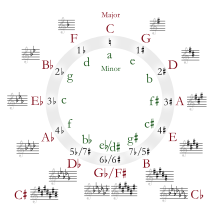

The dominant key is the key whose tonic is a perfect fifth above (or a perfect fourth below) the tonic of the main key of the piece. Put another way, it is the key whose tonic is the dominant scale degree in the main key.[8] If, for example, a piece is written in the key of C major, then the tonic key is C major and the dominant key is G major since G is the dominant note in C major.[9]

In sonata form in major keys, the second subject group is usually in the dominant key.

The movement to the dominant was part of musical grammar, not an element of form. Almost all music in the eighteenth century went to the dominant: before 1750 it was not something to be emphasized; afterward, it was something that the composer could take advantage of. This means that every eighteenth-century listener expected the movement to the dominant in the sense that [one] would have been puzzled if [one] did not get it; it was a necessary condition of intelligibility.

— Charles Rosen (1972)[11]

Music which modulates (changes key) often modulates to the dominant key. Modulation to the dominant often creates a sense of increased tension; as opposed to modulation to the subdominant (fourth note of the scale), which creates a sense of musical relaxation.

The vast majority of harmonies designated as "essential" in the basic frame of structure must be I and V–the latter, when tonal music is viewed in broadest terms, an auxiliary support and embellishment of the former, for which it is the principal medium of tonicization.

— Berry (1976)[4]

In non-Western music

[edit]The dominant is an important concept in Middle Eastern music. In the Persian Dastgah, Arabic maqam and the Turkish makam, scales are made up of trichords, tetrachords, and pentachords (each called a jins in Arabic) with the tonic of a maqam being the lowest note of the lower jins and the dominant being that of the upper jins. The dominant of a maqam is not always the fifth, however; for example, in Kurdish music and Bayati, the dominant is the fourth, and in maqam Saba, the dominant is the minor third. A maqam may have more than one dominant.

See also

[edit]- Predominant chord

- Secondary dominant

- Secondary leading-tone chord

- For use of the term "dominant" as a reciting tone in Gregorian chant, see church modes.

- Nondominant seventh chord

References

[edit]- ^ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 33. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0. "So called because its function is next in importance to the tonic."

- ^ Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony (3rd ed.). Holt, Rinehart, and Wilson. p. 118. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

V serves to establish the tonic triad...particularly evident at the cadence.

- ^ Berry, Wallace (1987) [1976]. Structural Functions in Music. p. 54. ISBN 0-486-25384-8.

- ^ a b Berry 1987, p. 62

- ^ Reti, Rudolph (1962). Tonality in Modern Music, p. 28, quoted in Kostka & Payne (1995). Tonal Harmony, p. 458. ISBN 0-07-035874-5.

- ^ Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy (2004). Tonal Harmony (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. pp. 197. ISBN 0072852607. OCLC 51613969.

- ^ Dahlhaus, Carl. Gjerdingen, Robert O. trans. (1990). Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, p. 143. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09135-8.

- ^ "Dominant", Grove Music Online[full citation needed]

- ^ DeVoto, Mark. "Dominant". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Forte 1979, p. 103.

- ^ Rosen, Charles (1972). The Classical Style. W. W. Norton. Cited in White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music, p. 56. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.