Gwendolyn B. Bennett

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Gwendolyn B. Bennett | |

|---|---|

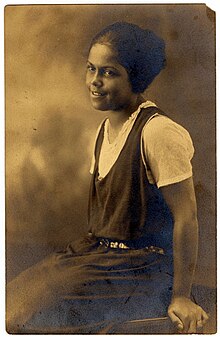

Photograph of Gwendolyn Bennett in the 1920s | |

| Born | Gwendolyn Bennett Bennett July 8, 1902 Giddings, Texas, US |

| Died | May 30, 1981 (aged 78) Reading, Pennsylvania, US |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, artist |

| Alma mater | Columbia University, Pratt Institute |

| Period | Harlem Renaissance |

| Notable works | "To a Dark Girl" |

| Spouse | Albert Joseph Jackson (1927–19??; dissolved) Richard Crosscup

(m. 1940; died 1980) |

Gwendolyn B. Bennett (July 8, 1902 – May 30, 1981) was an American artist, writer, and journalist who contributed to Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, which chronicled cultural advancements during the Harlem Renaissance. Though often overlooked, she herself made considerable accomplishments in art, poetry, and prose. She is perhaps best known for her short story "Wedding Day", which was published in the magazine Fire!! and explores how gender, race, and class dynamics shape an interracial relationship.[1] Bennett was a dedicated and self-preserving woman, respectfully known for being a strong influencer of African-American women rights during the Harlem Renaissance. Throughout her dedication and perseverance, Bennett raised the bar when it came to women's literature and education. One of her contributions to the Harlem Renaissance was her literary acclaimed short novel Poets Evening; it helped the understanding within the African-American communities, resulting in many African Americans coming to terms with identifying and accepting themselves.

Early life and education

[edit]Gwendolyn Bennett Bennett was born July 8, 1902, in Giddings, Texas, to Joshua Robbin Bennett[1] and Mayme F. (Abernethy) Bennett. She spent her early childhood in Wadsworth, Nevada, on the Paiute Indian Reservation. Her parents taught in the Indian Service for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In 1906, when Bennett was four years old, her family moved to 1454 T Street NW, Washington D.C.,[2] so Joshua could study law at Howard University and Mayme could train to be a beautician.[3]

Gwendolyn's parents divorced when she was seven years old. Mayme gained custody of Gwendolyn; however, Joshua kidnapped his daughter. They lived in hiding, along with her stepmother, Marechal Neil, in various places in the East, including Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Brooklyn, New York, where she attended Brooklyn Girl's High School from 1918 to 1921.[4]

While attending Girls' High, Bennett was awarded first place in a school wide art contest, and was the first African American to join the literary and dramatic societies. She wrote her high-school play and was also featured as an actress. She also wrote both the class graduation speech and the words to the graduation song.[5]

After her graduation in 1921, Bennett took art classes at Columbia University and the Pratt Institute.[6] In her undergraduate studies, her poem "Heritage" was published in The Crisis, magazine of the NAACP, during November 1923; in December of the same year, "Heritage" was included in Opportunity, a magazine published by the National Urban League.[7] In 1924, her poem "To Usward" was chosen as a dedication for the introduction of Jessie Fauset's novel There Is Confusion at a Civic Club dinner hosted by Charles S. Johnson.[1][8]

Bennett graduated from Columbia and Pratt in 1924 and received a position at Howard University, where she taught design, watercolor painting and crafts.[9] A scholarship enabling her to study in Paris, France, at the Sorbonne, was awarded to Bennett during December 1924. She then continued her fine arts education at the Académie Julian and the École du Panthéon in Paris.[10] During her studies in Paris, Bennett worked with a variety of materials, including watercolor, oil, woodcuts, pen and ink, and batik,[11] which was the beginning of her career as a graphic artist. However, most of her pieces from this period of her life were destroyed during a fire at her stepmother's home in 1926.[12]

Harlem

[edit]Bennett was a prominent figure and best known for the poetry and writing she produced that had a direct influential impact on the motives and essence of the Harlem Renaissance. Some ideologies that her works brought into perspective include the emphasis of Racial pride and the reminiscence of African values, such as music and dance. One of her most influential poems, Fantasy,[13] not only emphasized the racial pride of African-Americans, but also for women in general by shining light on possibilities that may not have been necessarily attainable for women during this time period.[14]

When Bennett left Paris in 1926, she headed back to New York to become the assistant to the editor for Opportunity.[15] During her time at Opportunity, she received the Barnes Foundation fellowship for her work in graphic design and the fine arts. Her artwork was also used for Crisis and Opportunity covers with themes that included diverse races, ages, classes, and/or genders allowing Bennett to display of the beauty in diversity.[1] Later, during the same year, she returned to Howard University once again to teach fine arts. While assistant to the editor at Opportunity she published articles discussing topics involving literature and the fine arts, and her column titled "The Ebony Flute" (1926–28)[6] distributed news about the many creative thinkers involved with the Harlem Renaissance.[16]

In 1926, she was also a co-founder and editor of the short-lived literary journal Fire!![17] Conceived by Langston Hughes and Richard Nugent, Bennett served as an editor for the single edition of Fire!!, along with Zora Neale Hurston, John Davis, and Aaron Douglas.[17] The failed publication is now reportedly regarded in some circles as a key cultural moment of the Harlem Renaissance.[17]

Finding inspiration through William Rose Bennet's poem "Harlem", she founded and named her self-proclaimed literary column "The Ebony Flute", another way in which Bennett was able to impact the Harlem Renaissance. "The Ebony Flute" was another contribution that Bennett gave to the Harlem Renaissance, as she emphasized Harlem culture and social life.[18] To keep updated with news, Bennett counted on her network contacts to foster the thriving and diverse environment that the Harlem Renaissance had to offer.[1] Bennett found ways to influence and contribute to her community without even publishing her own assemblage of poetic and literary works, including fostering young talent and serving on the editorial board of Fire!!.[19] The Women's Service League of Brooklyn honored her at the New York World's Fair in 1939 as a “distinguished women of today”, one of 12 black women so designated.[19]

Along with her emphasis on racial pride and her literary column, "The Ebony Flute", Bennett also shared a romantic vision of being African through romantic lyric. One way she expressed and shared this vision was through "To a Dark Girl", one of her more famous works of poetry. Creating an empowering aspect to African-American women features, Bennett's imagery and comparisons to queens are used to influence African-American women in embracing their blackness.[20] Bennett admired African-American artists and they made her feel proud to be part of that community, despite experiencing judgement from whites in the past.[21]

Although homosexuality was heavily criticized at the time, it had become common for both homosexual and straight female poets to write of lesbianism, and this included Bennett. Female, African-American poets had never before written about this topic, and even though it was considered taboo then, she and many other poets inspired other women to follow in their footsteps several years later.[22]

Harlem Circles, created by Bennett, were intended to be a place for writers to gather, share ideas, and spark inspiration. Over a period of eight years, some of the most famous Harlem Renaissance figures, such as Wallace Thurman and Langston Hughes met up in these groups and produced significant works as a result.[23]

Criticism

[edit]Her work during this period of her life was praised by her fellow writers in Harlem. The playwright Theodore Ward declared that Bennett's work was one of the "most promising of the poets out of the Harlem Renaissance" and also called Bennett a "dynamic figure... noted for her depth and understanding." J. Mason Brewer, an African-American folklorist and storyteller, called Bennett a "nationally known artist and poetess." Since Brewer was also a native Texan, he further stated that as a result of Bennett's Texas birthplace, "Texans feel that they have a claim on her and that the beautiful and poignant lyrics she writes resulted partially from the impression of her early Texas surroundings." Activist and author James Weldon Johnson described Bennett's work as "delicate" and "poignant".[22] This was an opportune time for female poets as many of them were not only taken seriously by peers and those in their community, but were also successful. Receiving such positive criticism from other members of the Harlem Renaissance helped Bennett gain recognition.[24]

Later life and Harlem influence

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

After marrying Dr. Albert Joseph Jackson in 1927, Bennett resigned from Howard University as the school's administration disapproved of their relationship. That same year, the couple moved to Eustis, Florida. Her time in Florida had a negative impact on her work as it was too far from Harlem to promptly receive news for her to write about in her column for Opportunity.

Due to the racism they encountered and their town's financial problems, they remained in Florida for only three years and moved to Long Island in 1930. Bennett began to write more frequently after working with the Federal Writers Project and Federal Art Project. After losing their home in Long Island, Jackson died in 1936, and Bennett moved back to New York.[1][25]

In 1940, she married educator and writer Richard Crosscup, who was of European ancestry.[26] Their interracial marriage was not socially acceptable at Bennett's time. Harlem remained Bennett's passion, however, and during the late 1930s and the 1940s she remained in the arts. She served as a member of the Harlem Artists Guild in 1935, and the Harlem Community Art Center was under her leadership from 1939 to 1944.[1]

During this time, she was active on the board of the Negro Playwright's Guild and involved with the development of the George Washington Carver Community School.[27][28] In 1941, the FBI continuously investigated Bennett on suspicion that she was a Communist and continued to do so on and off until 1959 despite no conclusive or evidential findings. However, this experience caused her to remove herself from the public eye and she began working as a secretary for the Consumers Union. [citation needed]

Bennett retired in 1968 and moved with her husband, Richard Crosscup, to Kutztown, Pennsylvania, where they opened an antiques shop called Buttonwood Hollow Antiques.[1]

Death

[edit]In 1980, Crosscup died of heart failure, and Bennett herself died from cardiovascular complications on May 30, 1981, aged 78, at Reading Hospital in Reading, Pennsylvania.[6]

Successes in poetry

[edit]Throughout her life, Bennett attained success in different fields of work. She was a poet, short-story writer, columnist, journalist, illustrator, graphic artist, arts educator, teacher and administrator on the New York City Works Progress Administration Federal Arts Project (1935–41).[citation needed][29]

Bennett's poems appeared in journals published during the Harlem Renaissance: The Crisis, Opportunity, William Stanley Braithwaite's Anthology of Magazine Verse (1927), Yearbook of American Poetry (1927), Countee Cullen's Caroling Dusk (1927), and James Weldon Johnson's The Book of American Negro Poetry (1931).[citation needed]

Bibliography

[edit]Short stories

[edit]- 1926 – "Wedding Day", Fire!!

- 1927 – "Tokens", Ebony & Topaz

Non-fiction

[edit]- 1926–28 — "The Ebony Flute" (column), Opportunity

- 1924 — "The Future of the Negro in Art", Howard University Record (December)

- 1925 — "Negros: Inherent Craftsmen", Howard University Record (February)

- 1928 — "The American Negro Paints", Southern Workman (January)

- 1934 — "I go to Camp", Opportunity (August)

- 1934 — "Never the Twain Must Meet", Opportunity (March)

- 1935 — "Rounding the Century: Story of the Colored Orphan Asylum & Association for the Benefit of Colored Children in New York City", Crisis (June)

- 1937 — "The Harlem Artists Guild", Art Front (May)

Poetry

[edit]- 1923 — "Heritage", Opportunity (December)

- 1923 — "Nocturne", Crisis (November)

- 1924 — "To Usward", Crisis (May) and Opportunity (May)

- 1924 — "Wind", Opportunity (November)

- 1925 — "On a Birthday", Opportunity (September)

- 1925 — "Pugation", Opportunity (February)

- 1926 — "Song", Palms (October)

- 1926 — "Street Lamps in Early Spring", Opportunity (May)

- 1926 — "Lines Written At the Grave of Alexandre Dumas", Opportunity (July)

- 1926 — "Moon Tonight", Gypsy (October)

- 1926 — "Hatred", Opportunity (June)

- 1926 — "Dear Things", Palms (October)

- 1926 — "Dirge", Palms (October)

Her work is featured in numerous anthologies of the period, including the following:

- Countee Cullen's Caroling Dusk (1924)

- Alain Locke's The New Negro (1925)

- William Braithwaite's Yearbook of American Poetry (1927)

Selected writings

[edit]- 2018 – Bennett, Gwendolyn. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance: Gwendolyn Bennett's Selected Writings. Edited by Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Govan, Sandra Y. "On Gwendolyn Bennett's Life and Career". MAPS: Modern American Poetry Site. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Gwendolyn Bennett" profile Archived October 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "J. Robbin Bennett". Digital Harrisburg. June 19, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Miller, Theresa Leininger (2018). Gwendolyn Bennett. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1602837. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Govan, S. Y. (1980). Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait Of An Artist Lost, p. 62. Available from ProQuest 303092580.

- ^ a b c "Gwendolyn Bennett", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Bennett, Gwendolyn (1902-1981) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. March 28, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Harlem Renaissance: Poetry". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Nelson, Emmanuel Sampath (2000). African American Authors, 1745–1945: Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Westport Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 19. ISBN 0313309108.

- ^ Johnston, Jessica (April 29, 2015). "Writer Gwendolyn Bennett". An Archive for Virtual Harlem. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Honey, Maureen (August 31, 2016). Aphrodite's Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 242.

- ^ Leininger-Miller, Theresa (2000). Bennett, Gwendolyn. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1602837. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ aapone (June 12, 2007). "Fantasy". Fantasy. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ aapone (February 4, 2014). "Double-Bind: Three Women of the Harlem Renaissance". Double-Bind: Three Women of the Harlem Renaissance. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ "Gwendolyn B. Bennett", Margaret Busby, Daughters of Africa, Cape, 1992, p. 215.

- ^ "Bennett | Pennsylvania Center for the Book". pabook.libraries.psu.edu. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Fire!!!", Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ "Gwendolyn Bennett - The Black Renaissance in Washington, DC". 029c28c.netsolhost.com. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Saltzstein, Dan (September 6, 2024). "Overlooked No More: Gwendolyn B. Bennett, Harlem Renaissance Star Plagued by Misfortune". New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Analysis of Gwendolyn B. Bennett's poetry". The Harlem Renaissance. February 11, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Hoffmann, Leonore (1989). "The Diaries of Gwendolyn Bennett". Women's Studies Quarterly. 17 (3/4): 66–73. JSTOR 40003093.

- ^ a b Honey, Maureen (2006). Shadowed Dreams: Women's Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813538860. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Gwendolyn Bennett: Harlem Renaissance". www.myblackhistory.net. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "Gwendolyn Bennett: Harlem Renaissance". www.myblackhistory.net. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Haas, Theresa (2005). "Gwendolyn Bennett". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. The Pennsylvania State University.

- ^ "Gwendolyn Bennett". Biography. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "archives.nypl.org -- Gwendolyn Bennett papers". archives.nypl.org. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Govan, S. Y. (1980). Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait Of An Artist Lost, pp. 39–40. Available from ProQuest 303092580.

- ^ "Gwendolyn Bennett Papers". New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

Sources

[edit]- https://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/bennett/life.htm

- https://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/bennett/life.htm

- Gwendolyn Bennett at poets.org

- From The Oxford Companion to African American Literature. William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. Copyright © 1997 by Oxford University Press

- Poets.org Academy of American Poets, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 901, New York, NY 10038

Further reading

[edit]- Cullen, Countee, ed. Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets. New York: Harper, 1927.

- Chaney, Michael A. "Traveling Harlem's Europe: Vagabondage from Slave Narratives to Gwendolyn Bennett's 'Wedding Day' and Claude McKay's Banjo." Journal of Narrative Theory, 32:1 (2002): 52–76.

- Johnson, Charles S., ed. Ebony and Topaz: A Collectanea. New York: Opportunity, National Urban League, 1927. 140–150.

- Govan, Sandra Y. "A Blend of Voices: Composite Narrative Strategies in Biographical Reconstruction." In Dolan Hubbard, ed., Recovered Writers/Recovered Texts. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. 1997. 90–104.

- Govan, Sandra Y. "After the Renaissance: Gwendolyn Bennett and the WPA years." MAWA-Review 3:2 (December 1988): 27–31.

- Govan, Sandra Y. "Kindred Spirits and Sympathetic Souls: Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Bennett in the Renaissance." In Trotman, C. James, ed. Langston Hughes: The Man, His Art and His Continuing Influence. New York, NY: Garland Press, 1995. 75–85.

- "Gwendolyn, Bennetta Bennett". Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

- Hine, Darlene Clark, ed. Black Women in America. New York: Carlson Press, 1993.

- Hoffman, Lenore. "The Diaries of Gwendolyn Bennett." Women Studies Quarterly 17.3–4 9[1989]:66.

- Jones, Gwendolyn S. "Gwendolyn Bennett ([1902]–[1981])." In Nelson, Emmanuel S., ed., African American Authors, [1745]–[1945]: A BioBibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000. 18–23.

- Shockley, Ann Allen, Afro-American Women Writers 1746–1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide, New Haven, Connecticut: Meridian Books, 1989. ISBN 0-452-00981-2.

- Wheeler, Belinda. "Gwendolyn Bennett's 'The Ebony Flute'". PMLA, vol. 128, no. 3, Modern Language Association, May 2013, pp. 744–55. mlajournals.org (Atypon), doi:10.1632/pmla.2013.128.3.744.

External links

[edit]- Houghton Mifflin's Gwendolyn B. Bennett

- See Gwendolyn B. Bennett's poetry in J. Mason Brewer's Heralding Dawn: an Anthology of Verse, published 1936 and hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Modern American Poetry Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Heath Anthology of American Literature

- The Black Renaissance in Washington

- A Biographical Sketch of Gwendolyn B Bennett

- FBI files on Gwendolyn Bennett

- Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.